Hugo Broos is the boss Bafana needs

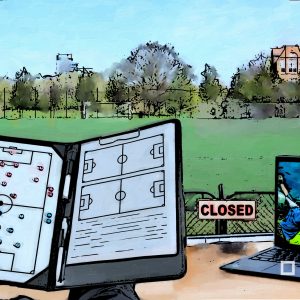

The Belgian coach may not be as glamorous as the others touted for the Bafana Bafana job, but his work ethic, approach and how he conducts himself make him a perfect fit.

Author:

5 June 2021

Bafana Bafana coach Hugo Broos is not popular. At 69, his triumphs and successes are often forgotten and don’t carry the weight they deserve. And as a personality, Broos isn’t sexy. His calm demeanour can be anathema to supporters who prefer the charisma of modern-day coaches.

This was most evident during his first press conference in Johannesburg. South Africans long for Bafana’s revival, having witnessed the team’s decades-long decline since their 1996 Africa Cup of Nations (Afcon) triumph. So the media and fans were unimpressed with Broos’ appointment, whose name didn’t resonate like front runner Carlos Queiroz or Bafana all-time top goalscorer Benni McCarthy. Had Broos come to pick up a final retirement cheque, the Belgian coach was asked.

This isn’t Broos’ first foray in Africa. In Cameroon, he was ridiculed at first. His inexperience in Africa was questioned. But he led the Indomitable Lions to Afcon glory in Gabon in 2017, lending credence to his reputation as a quiet winner.

Related article:

Broos was born in Humbeek, a village north of Brussels, to a housewife and a policeman. He enjoyed a youth of simple pleasures near the local castle and attended fishing contests in the area. At Catholic school, his education was stern. The priests ruled with an iron fist and his father, Dennis Broos, called on his son to behave like a role model.

The 1960s arrived. The Beatles released Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Celtic defeated Inter Milan in the European Cup and a teenaged Broos featured for FC Humbeek. His father died from heart failure and Broos repeated a year at school because of jaundice, but he excelled on the field as a defender, having switched position from attack.

Anderlecht chairman Albert Roosens, who is often credited for the club’s rise after World War II, convinced Broos’ mother that her son was just what his club needed. Broos’ brother-in-law negotiated that Anderlecht would deposit 100 000 Belgian francs (about €2 500) in a savings account the moment the young footballer completed his 10th game for the club. Broos would go on to play 454 matches for Anderlecht in 13 seasons, winning three domestic crowns in Belgium and three European trophies alongside club legends Paul van Himst, Rob Rensenbrink and Juan Lozano.

A reliable, quick and economic defender, Broos was one of the lesser gods. He was strong in the air and dispossessed his opponents fairly. In 1983, he moved to Club Brugge, winning yet another league title. It’s the club at which he got his first major coaching opportunity.

Lung power and possession

A novice to the profession at 39, Broos had a difficult task ahead. He succeeded then up-and-coming Georges Leekens, the star of the Belgian coaching guild. Top scorer Frank Farina had departed for Italy and Brugge’s talisman, Jan Ceulemans, had retired. Calm and composed, Broos rebuilt the team in a 4-4-2 formation, which sometimes morphed into a 5-3-2, with key roles for Daniel Amokachi and roving defender Lorenzo Staelens.

“Club Brugge without Ceulemans, wondered people. But Hugo found the right solutions,” says Frank van der Elst, who partnered Staelens in defence. “He was an attacking coach. His communication was perhaps not too good, not very open, but at least very honest. When we didn’t do well, he wouldn’t hide it. Broos was ambitious because of his past at Anderlecht. You had to win the league title at Anderlecht, otherwise you would have failed. He was someone who absolutely wanted to win.”

Related article:

Broos’ league title in his maiden season in 1992 was a coup, outsmarting favourites Anderlecht and KV Mechelen. His team didn’t possess the flair and flamboyance of the great Brugge outfits coached by Austrian Ernst Happel and Dutch Henk Houwaart, however, who were advocates of the one-touch Dutch school of thought known as “total football”. Broos’ Brugge wasn’t blue-collar either. He banned Leekens’ blueprint for physical football but kept his predecessor’s risk aversion. Brugge’s football was pleasing, but not refined. His side retained possession and employed lung power in the midfield.

“Hugo moved away from Leekens’ template of long balls with physically imposing players and scoring from set pieces,” explains Van der Elst. The club’s results weren’t all that different but “under Houwaart, Brugge was a little more spectacular, and that resonates. Broos never got enough recognition for his career.”

The Bosman ruling in 1995 transformed the game and, unable to retain talent, the Belgian league became a feeder for the top European leagues. Broos didn’t know how to deal with the gifted but capricious Robert Spehar, even if he switched tactics to accommodate the Croatian newcomer, who was looking for his own big-money move. “Hugo is a principled man,” explains Van der Elst. “The relationship with Spehar was difficult. He is a man of rules and decency. Perhaps he doesn’t deal as well with stars, but when you performed that was never an issue.”

Irked by the exit

SK Lierse pipped Brugge to the 1997 title and Broos, dismayed at how the club had planned his succession, left Brugge via the back door. At club level, he’d never ever again achieve the success of those heydays at Brugge. He spent five seasons at Mouscron, establishing the Walloon club in the top flight and reaching the cup final in 2002. His longevity and consistency with Mouscron impressed the then technical director of the Belgian Football Association, Michel Sablon, who hailed “his clear vision on development in football” as an asset.

Sablon, however, picked Aimé Anthuenis for the national team role and Broos succeeded the latter at Anderlecht. He introduced the 16-year-old Vincent Kompany in the first team along with Anthony Vanden Borre, who would later feature for TP Mazembe. Both teenagers were considered generational talents, but it was a gamble from Broos to trust the pair in defence at a club that didn’t tolerate defeat.

Broos demonstrated a knack for developing players. At Brugge, Amokachi, René Eijkelkamp and Paul Okon all secured impressive transfers. “Broos often looks towards youngsters for new blood in the team,” says Sven Vandenbroeck, his former assistant coach. “That is one of his qualities. At the start, Broos seeks younger players who can contribute to both a new team and new success.”

Related article:

But his tenure at Anderlecht was not going to last. Following a disappointing Champions League campaign, Broos was dismissed for the first time in his career in 2005 and, once again, his exit irked him. In his view, the Anderlecht hierarchy hadn’t offered him enough support.

Did Broos ever recover from his departure in Brussels? Perhaps not. His reputation nosedived. Broos was outdated and outmoded. He embarked on an odyssey, coaching in Greece, Algeria and the United Arab Emirates. All these stints were short and unsuccessful. In his biography, Hugo Broos: Always Winning, he admits that some of his choices were “irrational”. He became more and more frustrated by the lack of opportunities at home. Then, in 2016, he signed with Cameroon.

A young team takes shape

Broos and his assistant, Vandenbroeck, arrived in Yaoundé under a cloud. The local press was sceptical of the little-known Belgian, who had no prior experience in Africa.

But Broos adapted quickly to his new environment, even if the cultural differences were sometimes an obstacle. “He was astute at judging what was important and what wasn’t,” says Vandenbroeck.

Instead of picking fights or fretting over logistics, Broos imposed discipline and wasted no time in making his mark on the team. He renewed and cleaned up the squad, dropping le cadre, a group of established stars who wielded serious influence behind the scenes but refused to commit to the team. Drawing twice with South Africa, Cameroon qualified undefeated for the 2017 Afcon, but expectations around the team remained low going into the finals in Gabon.

Related article:

Broos insisted Cameroon drop the preparation in Morocco and warm up instead in Equatorial Guinea, where conditions mirrored those of the host nation. It was a crucial camp for building physical conditioning and team spirit. Broos’ young team was taking shape. Captain Benjamin Moukandjo liaised between the coach and the players. Vandenbroeck, who was 38 at the time, also helped bridge the age gap.

“He was very clever in that he knew which messages he had to deliver himself and which messages the captain should deliver,” says Vandenbroeck. “He was very apt in managing the group and individuals. We left a lot of stars at home, but we still had Benjamin Moukandjo in France and Vincent Aboubakar at Porto. Those were not the easiest characters to deal with.”

In the build-up to the final, Broos reduced his players’ workload to focus on relaxing their minds. “He knew what he was doing, he participated in enough finals himself,” says Vandenbroeck. “At half-time, he emphasised that we were physically better and that we had to keep pushing to make the difference.”

King of the underdogs

His team pressed on and the underdogs combined attitude with aptitude, applying hard work, grit and bursts of flair to triumph. In the 87th minute, Aboubakar struck with an elegant half-volley to crown Cameroon continental champions at the expense of Egypt. At the final whistle, Broos, in a white shirt, sprinted on to the pitch to hug and dance with the match winner.

“Yes, he was emotional, but not exuberant,” recalls Vandenbroeck. “The relief after the Senegal match was bigger because they were sky-high favourites. We went to the hotel and had dinner next to the pool and I jumped in with the players. The coach drank his customary beer and that was it. Deep down, we were of course very proud.”

To an extent, his victory in Africa represented redemption for Broos after a decade without recognition at home. He was the first Belgian coach to win a continental tournament. Even so, his Cameroon tenure was subject to scrutiny. Had this modest team simply ridden their luck for three golden weeks in Gabon?

Related article:

“As coach of Cameroon, you need the attitude of delivering in the short term with a strong team,” says Vandenbroeck. “We had good players, but Cameroonian players don’t belong to the top of Africa technically. Mali, South Africa, Senegal and Morocco, that is a different story, all at top clubs in Europe, technically and tactically better. His attitude in South Africa will be different from what we envisaged in Cameroon.”

At Cameroon and Mouscron, all those years ago, Broos demonstrated that he was capable of taking the underdogs to success. And at Brugge, he combined people management, tactics and potent football to succeed in the 1990s. But South Africa is a different proposition.

Bafana still like to think they are among the continent’s heavyweights, even after years of chronic underachievement. With major tournaments on the horizon, Broos will need all the ingredients that propelled him to success in the past to prove that he isn’t simply another coach who fails to prove their mettle.