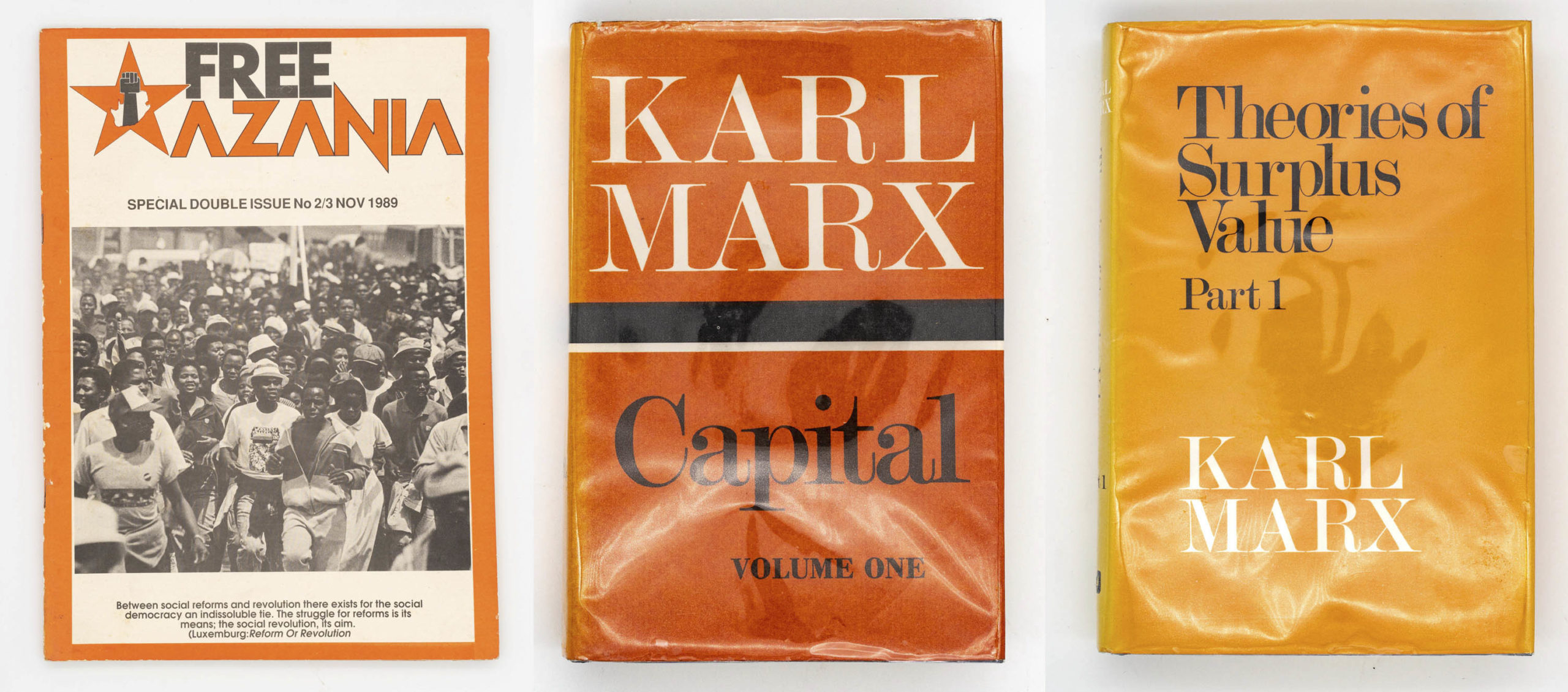

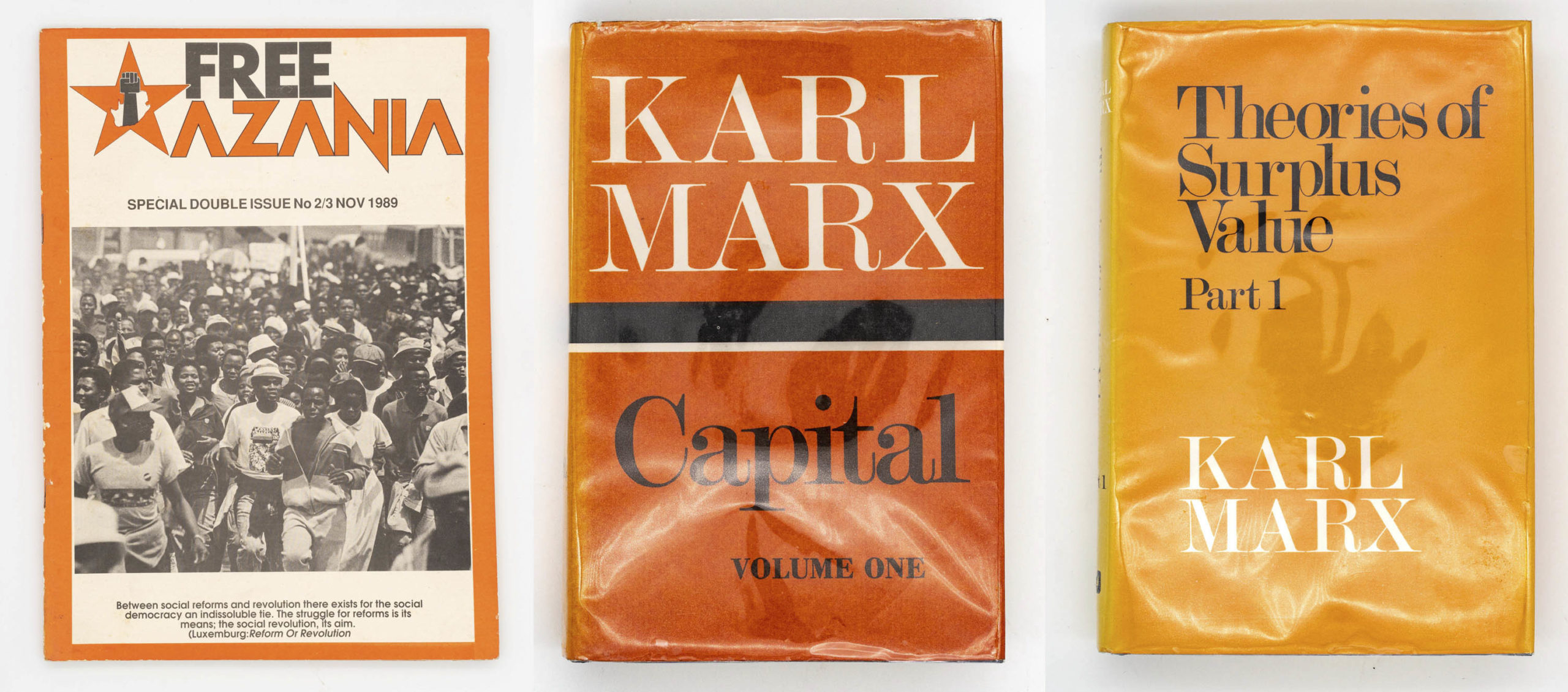

How Leon Trotsky birthed a bookshop

Borrowing one of the Marxist revolutionary’s books sparked a love of political reading for the owner of Surplus in Cape Town, where a huge collection can be found.

Author:

29 July 2021

Surplus, a radical pop-up bookshop situated on Albert Road in Lower Woodstock, Cape Town, is just a stone’s throw away from the Old Biscuit Mill, a hallmark of gentrification in the area. Nestled between a tattoo parlour and a T-shirt printing shop, it is easy to miss if Andre Marais, whose book collection fills the shop, is not outside wearing his black beret and smoking a cigarette.

A cabinet in the street-facing window contains a bust of Chinese communist revolutionary Mao Tse-Tung that rests next to a first edition paperback of his collection of poems. Also in the cabinet, and visible from the pavement, are three volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital as well as his Theories of Surplus Value.

The shop is one large room, its walls lined with bookshelves. A large white cloth bearing images of the pope, Jesus dragging a cross and the word “Cruceviction” covers a table in the middle. To the left of the table, a Cuban flag hangs from the ceiling.

Towards the back of the shop, next to a shelf labelled “Apartheid Ephemera”, a coffee machine stands at the entrance to a doorway that leads to the kitchen, signalling to visitors that food and drink are available. But the books are the main attraction and for would-be buyers Surplus is a treasure trove.

For Marais it’s more complicated. “I sometimes don’t think that people understand your connection to books, that it’s more than just books. It tells the story of your life,” says Marais.

His books begin telling his story in the mid-1980s when his family lived in Lansdowne. It was shortly before they were evicted during apartheid’s forced removals and sent to Hanover Park, and Marais was in his final year of high school.

Greg Ruiters, a teacher at Oaklands High where Marais was a pupil, lent him a copy of Leon Trotsky Speaks. It was the first political book he was given and, unbeknown to either of the two, would become the first book in a collection that Marais estimates to be 40 000 strong.

An awakening and education

“1985 was an important year for my generation, like 1976 was for others,” he says, referring to the year he was exposed to political ideas and got involved in activism. While in high school, Marais joined the United Democratic Front’s youth movement in Silvertown. “It was never large, it was never more than 30 people. But the people that were there played an important early part of my development as an activist,” he says.

In the youth movement he encountered a “suitcase library”, which was filled with books that were banned under apartheid. In addition to political books, the suitcase contained African and Latin American novels as well as poetry collections.

For Marais and his comrades, activism and reading went hand in hand, despite their not having as much time to read as they would have liked owing to their activism activities. “There was the activism and then there was [developing] theoretical understandings of what apartheid was and what capitalism was. Those were the seeds that were sown in terms of my interest in books,” he says.

“Politics means connecting to the world. The best activists that I knew – and I would hardly list myself among them – would embrace everything. They thought everything was worth reading.”

Once his passion for books got triggered, Marais began going to “every second-hand shop” to dig for books. “I often didn’t have money and I would buy a book for R2 that I thought was important,” he says.

As with the suitcase library, which he went on to inherit, Marais’ own book collection diverged from purely political writing to include topics such as arts and culture, music, progressive novels and sport, evidenced by the books on sale in the shop.

Becoming a shopkeeper

Marais has had a variety of occupations ranging from teaching to being the culture editor of Amandla! magazine, which was run by the Alternative Information and Development Centre, a non-governmental organisation of which he was a founding member. He ended up working directly with his own books by making them available to young people as libraries through various organisations.

In 2020, Marais had secured funding to run a library for students at Athlone High School, but the project fell apart when the schools closed in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and he was left without an income. To make ends meet, he sold books from his collection to The Book Shoppe in Tokai, which is how he met the owner, Ray van Wyk.

“[Marais would] bring me more interesting sort of political stuff and we started talking about the books and about [his] collection,” says Van Wyk. “The joy of dealing with books is that you just get … crates and boxes full of stuff. You dig through it and from time to time you find something worthwhile.”

With Marais’ books it was different. “There was so much incredible stuff that you just couldn’t believe,” says Van Wyk. “I think there’s just a major lack of good left political material in South Africa. The good publishers are seldom brought into the new bookshops, so there’s very little of that that sells, and then there’s very little of it that ends up on the second-hand market. So it was great that there was suddenly this huge collection.

“We eventually got to a point where I think the volume of stuff that he was wanting to sell was just too much for the shop. And one day I said look, let’s talk about what we can do. And we went for a beer in some pub here in Retreat, just over the train tracks.”

That’s when Marais came up with the idea of setting up Surplus as a pop-up shop in collaboration with Van Wyk. He has had to give up on his ideal to have his books available in a library for now, yet Surplus seems to fill a space somewhere between a second-hand bookshop and a library.

Operating under lockdown

Soon after opening the shop on 25 May 2021, the pair were approached by the Salt River Heritage Society and Reclaim the City, two local activist groups that wanted to use the space for meetings, film screenings and workshops. The owners had also planned a special event on Paulo Freire’s work as well as one in collaboration with the Friends of Cuba Society.

But because of South Africa’s third wave and the adjusted level four lockdown, all gatherings were put on hold, though the book-selling aspect continued and people still visit in search of important books.

Surplus exceeded Marais’ expectations in its first month of operation, before the lockdown. Musing on the possible reasons for this, he says, “Maybe the success of this shop in the [first] month is that people have the same nostalgia for [the] serendipitous [experience] of coming into a shop for one book and [finding] another book.”

Whatever the reason for the initial success, Surplus has given Marais the opportunity to once again experience the joy of connection as a result of his books, even though they are books he has decided to let go.