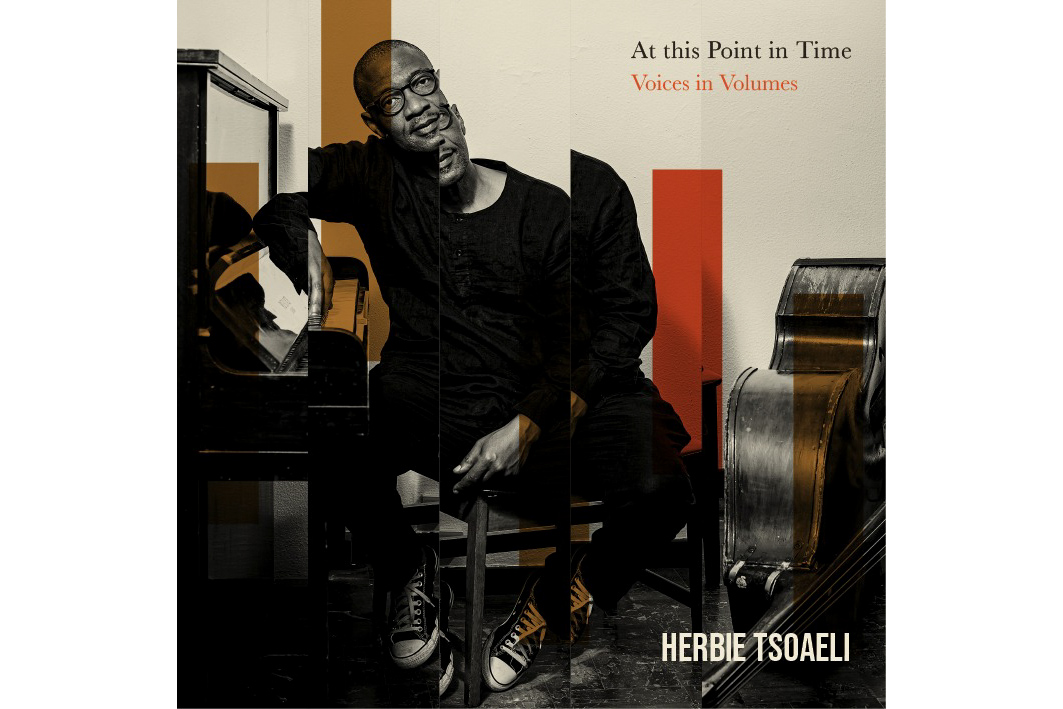

Herbie Tsoaeli’s temple of timelessness

The acclaimed bassist returns with a second album, At This Point In Time launched in early November. It is rooted in heritage and pays homage to his jazz ancestors.

Author:

30 November 2021

Herbie Tsoaeli’s fans call him uMalume (uncle) in respect of his experience, wisdom and generosity of spirit. That’s the first thing the bassist shows when my arrival at Johannesburg’s Radium Beer Hall for our interview gets delayed. Far from expressing impatience, Tsoaeli assures me I’ve arrived right on time. “When you said you were late, I thought, you are on African time because African time has principles which [go]: arrive safely at your destination, as long as you’re going to be there.”

Tsoaeli is seated alone on the isolated upstairs floor of the bar. He calls it his temple and being alone in this space is where he finds sanctuary. A cool breeze that day reminds him of the sea breeze in Cape Town, where he grew up.

Nearly a decade since his debut award-winning album African Time (2012), Tsoaeli returns with At This Point In Time: Voices in Volumes, released on 5 November. For him, time is not something that can be chased or caught up. So, despite the nearly 10-year period between albums, this one arrives right on time, too.

This notion and metaphor of time filters through our entire conversation, which stretches to nearly four hours. Tsoaeli’s philosophy revolves around African time, as an ideology and as a community ethos. It’s far-out stuff, but there is wisdom behind what he has to say.

Tsoaeli is somewhat of a professional neologist and has created his own lexicon and philosophies through which he understands the world around him. His way of speaking is not unlike a jazz composition, with wild improvisation thrown in but at other points phrases that repeat themselves in different forms. “Terms and thoughts” is preferable to “terms and conditions”, “busimessness” denotes the messiness of everyday business, “disturbance resistance” is his mantra for fending off negative energy… and on it goes. Those who encounter the elder learn fast how to switch to his code.

Tsoaeli launched his album the night before our meeting, to coincide with a performance at Jazzfest Berlin in Johannesburg. In the show, he dedicated a deeply touching unreleased song to his daughter called The Beauty In You, and the packed crowd rooted for the elder who they had so badly missed seeing on stage.

Speaking to the past

“My ear is like a conveyor belt in a factory… the conveyor belt of Afrikan time,” he says about how he has picked up all kinds of music. In more ways than one, Tsoaeli’s album pays tribute to those who came before him. “I’m not playing my music. I’m playing music from my ancestors and all the superpowers,” he says.

This is best exemplified by the song Abadala Baholo, which refers to elders such as bassist Johnny Dyani, drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, saxophonist Winston Mankunku Ngozi and pianist Tete Mbambisa. It also pays homage to family members, teachers and community figures. “Abadala baholo (elders) will always stay in our hearts as they have been our guidance in our homes and lives,” Tsoaeli says.

Voices in Volumes in the album title refers to those voices that have echoed through Tsoaeli. “The two and a half decades of doing my apprenticeship in music with the elders in different formations of bands have taught me so many things about the lives we live as artists. I decided it was time to voice my voice out!” he says.

Growing up in his grandmother’s house in Nyanga East, Cape Town, his youth was a collage of sound. “There was music all around me. The sounds of gospel on one side, the Zionist church on the other, traditional healers at the back of the house and then the hostels playing music from the mines and the gathering ceremonies of all different backgrounds.” He refers to his grandmother often, paying tribute to the teachings, morals and values she passed down to him.

Tsoaeli’s mother listened to jazz and his uncle was a bass player. He also grew up watching the greats of Cape Town jazz. “Whenever they were rehearsing, I’d be there.” Later in life he would perform with those very musicians. “Those were the spaces I was crazy about. And those spaces enlightened my way of thinking and how I forge ahead,” he says.

Having attended various community music schools, the bassist is largely self-taught. While he does not write music, his entire being is music itself. On stage, he swings his bass wildly and stomps his foot down hard as he sings, even when there aren’t any lyrics.

Growing up he was a “frustrated saxophonist” and tried many different instruments, including drums, before settling on the bass. He insists that it was sound and melody that he was drawn to with the saxophone. The smooth tones of vocalists in bands such as Earth Wind & Fire intimidated him, but he eventually found his voice. Many tracks on the album feature him singing.

A new pace

The new album plays with different paces of time. At moments, it speeds up, such as in the chugging, driving bassline of East Gugs Skomline to Khaltsha, referring to the central train line that would get him home. The pace is slower and there are tones of melancholy at other times, such as in Alone On Your Own, something he says he has always been. The album is also about the process of healing.

Tsoaeli has developed a “natural time framework” for his life and work. “I’m rethinking the notion of time and seeking a way of liberating myself. There’s so much happening in the midst of time as it is moving forward and never goes backwards. But the past, present and future is another time frame that one draws from Afrikan time for mental freedom. Time has so many frequencies and speeds, which at some point translates into musical symbols [such as pulses, anticipation, syncopation, tacets and dischords]… At this point in time I guess I’m dealing with the time within.”

He considers his African time philosophy as a research of oneself in the midst of those who came before him, looking at heritage as a source of seeking knowledge and wisdom.

For Tsoaeli, “Afrikan time music is an institution of consciousness. As Biko told us, ‘You write what you like’, and at this point in time I’m on that path.” He continues: “I played with Zim, he was on to his own path. I played with the master Abdullah, he was on his own path – that I respect so much. Bra Winston, own path. Bheki Mseleku, own path. Ezra Ngcukana, own path. Duke Makasi, own path.”

The album came about through the hard work of a team of supporters, who helped guide the project. “I call them honourables. These guys have been coming to all my shows for almost 10 years now, wherever I play. They’ve been hearing a cry … I would love to thank them all, hence the word honourables.”

The “cry” he refers to is one of not having enough funds, despite wanting to release a second album. Businesspeople and fans Moeketsi Boikanyo, David Njuki and Mduduzi Godlo came together to form iSandi Sarona (Our Sound), an independent label co-run with Tsoaeli, to release the record. The label handles all the admin, or “busimessness”, while Tsoaeli concentrates on the music. The process got under way last year and the album was recorded in March this year.

Future time

Tsoaeli initially intended to feature elders on a few songs, trumpeter Stompie Manana and saxophonist Barney Rachabane, but could not because of funding issues. “I decided instead to honour them with the song Abadala Baholo.” Rachabane died in mid-November; Tsoaeli had played with him previously. “Bra Barney and his music and his teachings live on in my life,” he says.

For the album recording, Tsoaeli assembled a dream team of core musicians and frequent collaborators: Andile Yenana and Yonela Mnana on piano, Sisonke Xonti on tenor saxophone, Ayanda Sikade on drums, Tshepo Tsotetsi on alto saxophone, Stephen Sokuyeka on trombone and Sakhile Simani on trumpet. There are additional accompanying vocals on some tracks.

While honouring his elders, Tsoaeli is an elder himself who is ushering in the future generation. He is excited to be working with younger musicians.

He says with hope: “The only time when you can have an eye for any artist is to go out and scout. And go to shows and watch them play in different formats, which is what I normally do at all times.

“I go out and watch gigs and this is how I spot the young musicians who are energetic and who are beautiful. Because as you can see, jazz is buzzing in South Africa. And they’re all wonderful and beautiful doing great stuff, producing their own records and performing. So, it’s just beauty all around.”