Gabrielle Goliath creates songs for survivors in scratched melodies

The artist’s new exhibition, ‘This is a song for…’, interrupts song recordings in the manner of a stuck record to jar audience members into experiencing how rape continues to interject itself into …

Author:

12 July 2019

Song dedication is a memory-soaked love language. In this tradition, the cocktail of melody, time and intention produce pure emotional alchemy. Gabrielle Goliath is a master alchemist.

Goliath’s latest exhibition, This Song is for…, draws on the dedication song tradition to render the experience of surviving rape. Rather than seamless nostalgia or escape, however, each of the eight songs in the 2019 Standard Bank Young Artist for Visual Art’s song cycle is interrupted, as a few bars are repeated in a manner resonant of a scratched vinyl record.

The repetition lasts for several minutes, seemingly endless, shifting each performer’s song, as the difficulty is made visible. National Arts Festival Committee member and this year’s visual and performance art curator, Ernestine White-Mifetu, says this sonic disruption represents how each rape “forever created a scratch in the lives of the survivors”.

Related article:

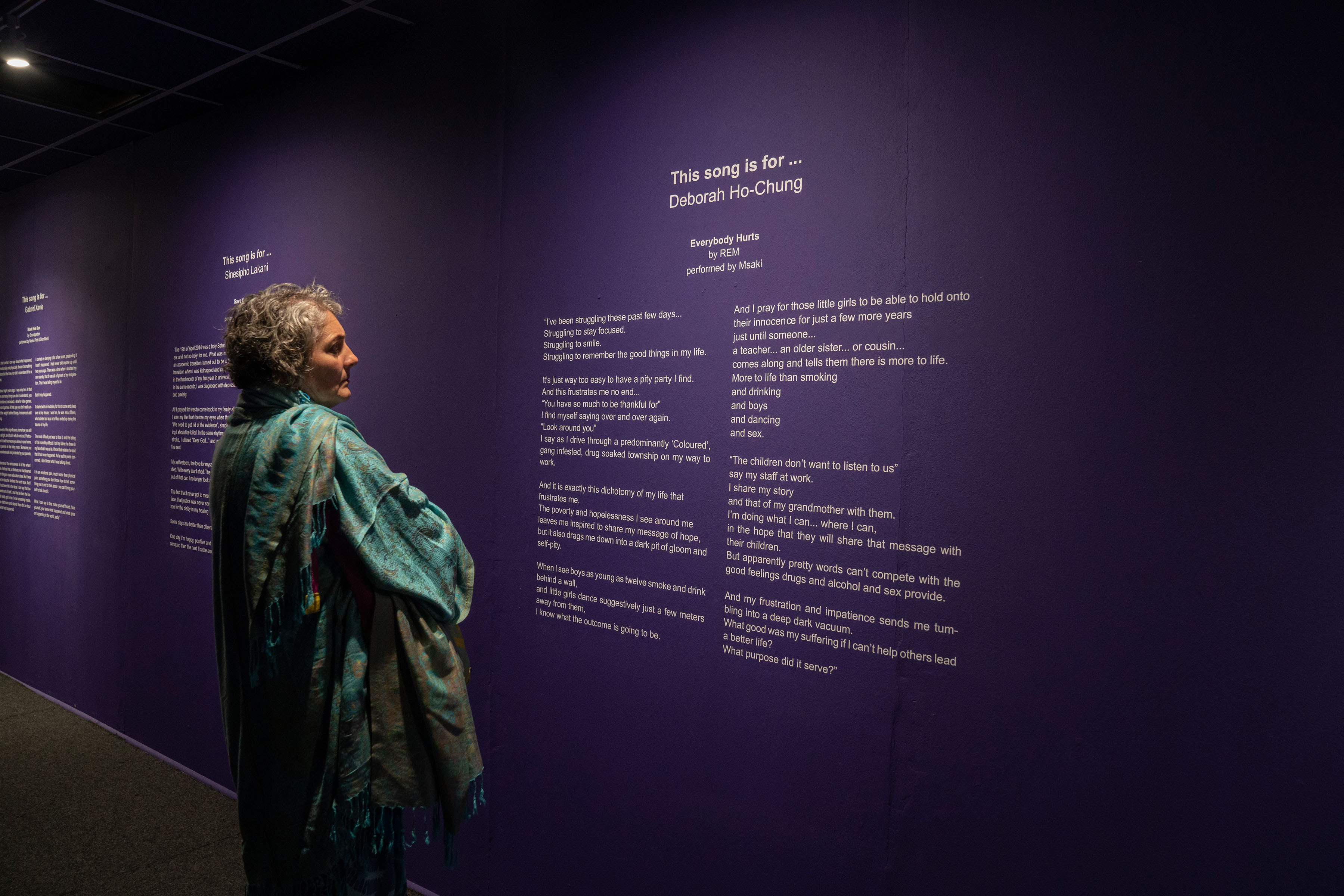

The installation, which showed during the National Arts Festival at the Monument Gallery in Makhanda, uses multiple formats, in signature Goliath style. This is the artist’s preference for a “more capacious approach to art” in which she is “open to an expanded field of sound, touch, ritual, performance and more”. On one side of the room, eight individual testimonies of rape survival are printed on a purple wall. Two of the survivors prefer not to disclose their names. The remaining six appear above the title of the chosen song, its writers and performers, followed by the survivor’s rape narrative.

Across the gallery space, two giant television screens play a two and a half hour song cycle of cover versions performed by women and/or a queer-led ensemble. Placed like this, the songs chosen by the survivors reverberate back at them.

A scratch in survival

The “scratch” in each melody is an apt metaphor for the scratch created by rape in a survivor’s life. A scratched record irreparably alters a song as rape does its afterlives, disrupting the ease of seamlessness. The scratch is permanently etched on to the psyche. Rape may not define a survivor’s life. After all, the survivor continues to feel and experience a range of other life textures and emotions. Still, there is no escape; the song cycle returns to the moment of disruption in each song. Each return is recall – sometimes expected, often unannounced.

In this installation, as in Elegy and Faces of War before it, Goliath evades the traditional artist-audience distance that we expect from the gallery space. Instead, the length of the sonic disruption discomfits the audience.

A woman who came to view the installation commented that the broken record was distracting her from reading the writing on the walls, announcing that she would return once the audio had been repaired.

Goliath’s chosen form creates this desire for relief in her audience, as an echo of the desire of the survivor. However, when the repetition does eventually pass, this too comes with discomfort and anxious anticipation of its return.

In old-fashioned vinyl records, the scratch did not resolve itself. A hand would need to lift the needle away from the scratch. Something would be irrevocably lost, causing another disruption to the irritating repetition that had become a pattern. Relief would pass, the needle would return to the scratch.

An apt metaphor

That the scratched record is an apt metaphor is clear from the survivor’s words on the walls. The narrative of one survivor, Flow, personifies the rape as death’s knock readying to steal her soul. This attempt is only partially successful. She does not die in the rape, even if a part of her does.

Similarly, Nondumiso Msimanga’s words powerfully explore the paradoxical death dance rape injects into her life. Pitting her will to live against her desire for relief, she insists, “I’m a fighter and every day I’m fighting for my life, fighting for it to matter.” Msimanga’s words contain the recognition echoed in all the narratives in one form or another, that rape was an attempt to erase her. To matter, then, is to survive; it is to stay alive long after the sound of death’s knock.

Deborah Ho-Chung’s words tie in with those of Msimanga and Flow to ask, “What good was my suffering if I can’t help others lead a better life? What purpose did it serve?”

This onerous struggle against meaninglessness, death and disposability complicates how to speak about the experience of rape. Gabriel Savie’s statement that “the telling of it is incredibly difficult” is as much about the difficulty of finding appropriate language as it is about the threat of revictimisation.

When they choose songs, which are then sung and played for them by Goliath in this installation, these survivors are also choosing beauty and life. Living with interruption, they grasp at connection and continuity, as symbolised by the song cycle, and the unstuck parts of the music. The song cycle stands for their lives, the interruptions are triggers as well as empathic recognition.

Sinesipho Lakani’s testimony underlines the haunting of repetition. “But again I am forced to relive the moment every time I hear a story of a raped woman.” Here, repetition creates pattern recognition. In the midst of a national rape crisis and heightened global awareness of endemic sexual assault, Lakani’s sentiment carries additional poignancy.

White-Mifetu notes that as Goliath’s audiences, after accepting that the sonic disruption will not end, we try to grow accustomed to the scratch. When it does end, we experience both sonic relief and a new discomfort as the melody returns because its beauty is haunted by awareness of the scratch’s return. Rape need not define life, but it does poison life. The battle to survive is the fight to hear the music while knowing the scratch is permanent.

The first and eighth narratives belong to women who prefer to remain unnamed. The first asserts that “survival is a prayer”, a hopefulness and yearning for answered prayer. The eighth ties in with this testimony: “I will not write of the depths I have sunk to. I will simply sing, meditate, pray. Sing, meditate and pray for us.” Here, too, the struggle for definition and connection.

A song for survivors

This Song is for… is as much about the eight specific survivors whose words line the walls of Goliath’s exhibition space as it is a song for survivors beyond those walls. The story of rape is not a single one even if it creates patterns. Goliath stages threads and distinctive voices, quirks and tastes in text presented as letter, poem, testimony, prayer and news article.

Audiences pay attention to difference and are prompted to take cues from the specific in furtherance of a language of undoing rape. For Corey Spengler-Gathercole, who writes a letter to her rapist and former friend, this commitment is clear: “I will fight for all women who are hurting because of someone like you.”

This song is for… is a scratchy melody, a compassionate and brilliant work on memory and hope. The songs are also for millions more who are similar to Goliath’s eight, and also different from them. It is not an exhibition about amplifying voices or breaking silences. Goliath’s is an invitation to feel differently about rape and be changed, and therein lies the hope for undoing rape.

The Rape Crisis Centre number is 021 447 9762

This song is for… is now showing at the Standard Bank Arts Gallery, Corner Simmonds and Frederick Streets, Johannesburg from 26 July 2019 – 14 September 2019.

![2 August 2018: “I decided to kill myself because when my last-born experiences what I had been experiencing, [it] was [a] torture ... I couldn’t withstand…”](https://www.newframe.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/image-24-442-150x150.jpg)