From slave to major composer – then erased again

Like most contributions made by black people to the classical canon in Britain, Ignatius Sancho’s work has been overlooked, even though he had a hand in shaping musical culture.

Author:

6 October 2020

Research into early black intellectuals, including the likes of Phillis Wheatley, Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho, is often linked to the Atlantic Slave Trade and abolitionism. But it is not often that we look specifically at Ignatius Sancho and how his life story connects classical music to the business of slavery. Sancho is remembered as a man of letters, but not as an accomplished composer in 18th-century England.

This absence – and the general lack of research into black composers during this period – comes as no surprise. Until recently, it was seldom mentioned that one of Europe’s most important composers, George Frideric Handel, invested in the slave trade. The German-born composer, whose work is considered foundational to music theory, was the first to compose oratorios in English, beginning with the epic Esther in honour of John Brydges, the Duke of Chandos. The duke and Handel crossed paths at the Royal Africa Company, which traded enslaved people from its establishment in 1672 through to the 1720s, with a monopoly in trafficking black people to the Americas and Europe.

Handel began investing in the Royal African Company in 1720 to cushion any shortfall from his work as a composer. It is unclear under which company Sancho was traded as a baby, but to talk about Handel and his great works – from Messiah to Water Music – is to talk about scores of music sustained by the Middle Passage, the forced crossing from Africa to the Americas.

-

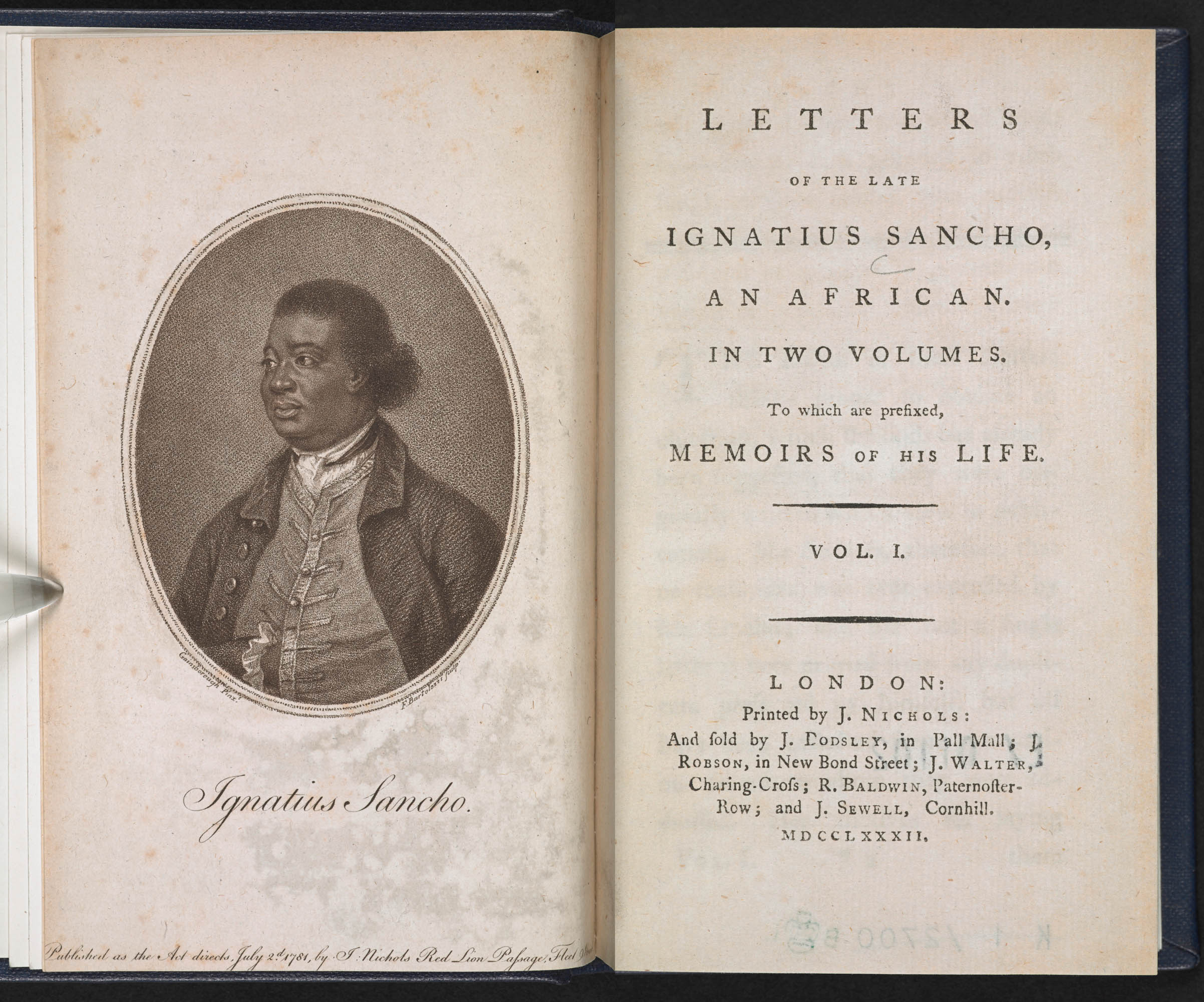

A composite image of the inside of The book Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African was printed in 1782, two years after Sancho’s death, and became a powerful tool in the campaign to end slavery. Source: The British Library -

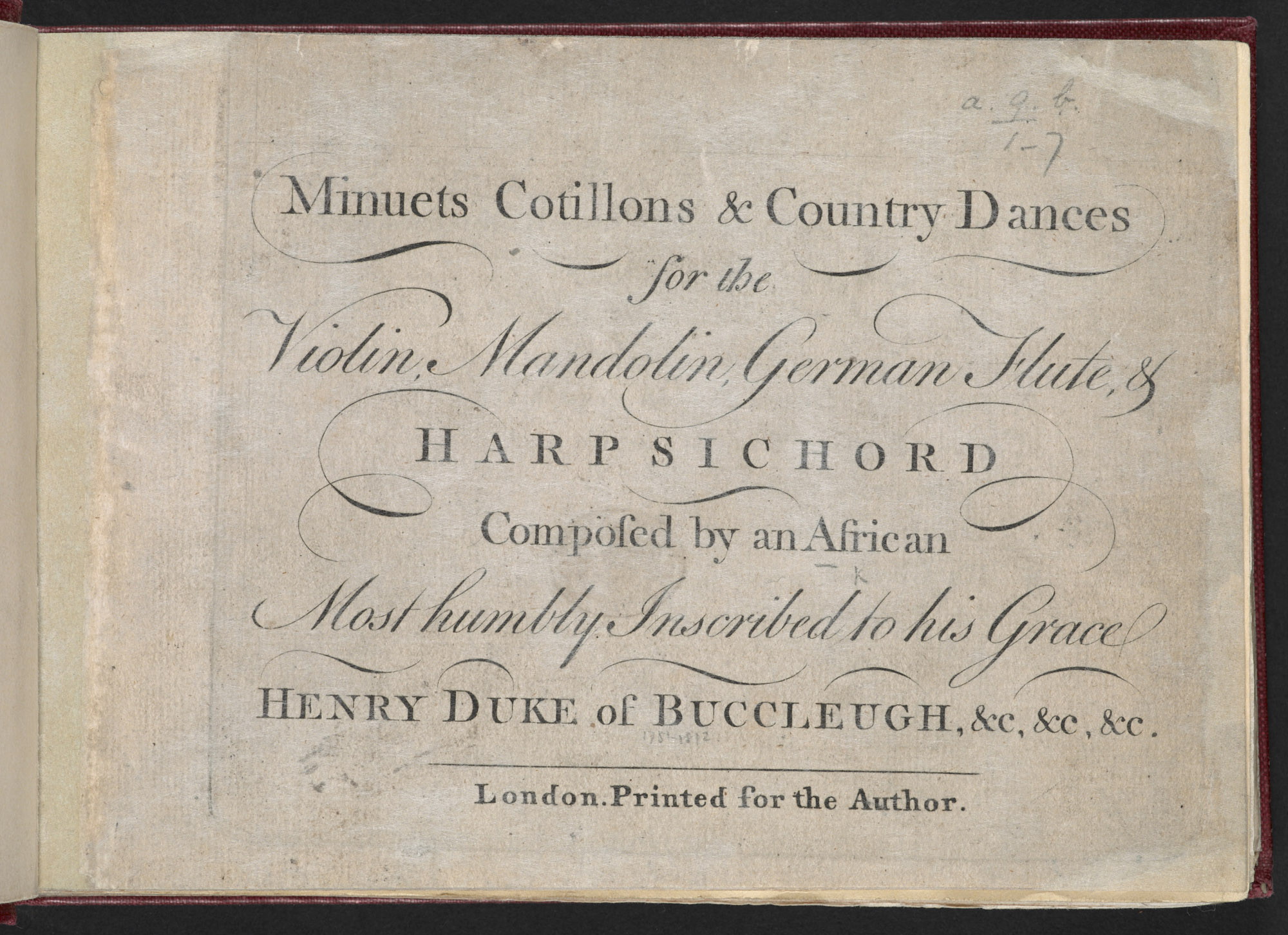

One of the music and dance books written by Sancho published in 1775: Minuets Cotillons & country Dances for the Violin, Mandolin, German Flute, & Harpsichord. Composed by an African. Source: The British Library

The life of Ignatius Sancho

According to his posthumously published memoir, Sancho’s mother died of an undisclosed disease when he was barely two years old. His father drowned in the Atlantic Ocean after jumping off a slave ship – many of the enslaved chose not to find out what awaited them. Sancho was then sold to three sisters in England, becoming their servant. (Another recent turn in slave history places white women at the centre of the brutality and not just as aloof wives of slave masters.) He then met John Montagu, the former governor of Jamaica, who exposed him to literature and culture as a boy. Sancho escaped his slave mistresses with the help of Montagu’s widow.

Sancho’s work as a musician began with his relative freedom. In addition to his books of minuets, or dance scores, published between 1767 and 1770, Sancho published A Theory of Music: A Collection of New Songs and Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1779 between writing plays, starring in Shakespeare’s Othello and later owning a grocery store. It is through Sancho that we are introduced to a music culture black British people both free and enslaved had a direct hand in influencing. Perhaps this wouldn’t be surprising if the classical canon were explored in its entirety. Then again, Britain has somehow managed to evade accounting for its role in constructing the brutal world we know. Sancho invites us to undo the erasure of black people’s contribution to the canon.

Major composer

Sancho’s contribution to classical music was through the minuets, a musical dance form popular with white aristocrats. In her biographical essay of Sancho, Josephine Wright writes, “Black musicians were recruited – indeed, often forcefully conscripted – for British regimental bands. A few men succeeded in breaking down racial barriers to prosper in aristocratic English society as professional musicians, performing with major symphony orchestras and chamber groups in London.”

Sancho enjoyed a certain privilege equal to the tenure of some major composers in England. He was a sought-after artist, even though today his place in the canon is all but ignored. This privileged space also calls into question the problems of the notion of genius. Sancho as an exceptional figure in Georgian England didn’t do much to recast the black British population as human rather than inferior. It saved one man.

Related article:

Yet, at the same time, not entirely, as his work is marginalised. His visibility contributed to turning the tide toward the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade, but his special position as a so-called genius – genius being a prerequisite to be seen as human while existing in black skin – means the general population failed to recognise black people as human. His erasure in the classical canon speaks to how easily racism can overturn progress when that progress has relied on problematic reasoning in the first place.

Sancho’s work was published posthumously by white abolitionist Frances Crew with a foreword by Joseph Jekyll, who sought to present the composer’s letters and minuets as evidence of the intellect of black people.

There are far better ways of reinstating black composers in the canon and framing the likes of Sancho without succumbing to the method used by Crew and her colleagues. Perhaps we could write about Sancho today in the same way we would an erased white composer – such as Augusta Holmés, a French woman commissioned to compose work in honour of the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution – by analysing his contributions and approach to the classical form in the same ways we do for his contemporaries.