Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary spirit lives on

A new collection of essays uses the works of the psychiatrist and radical political philosopher to explore how a community’s language and capacity for thought and wit threaten the state.

Author:

29 June 2022

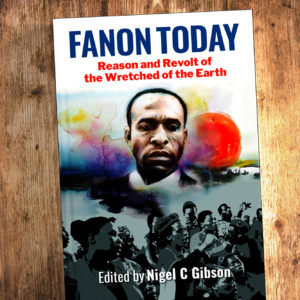

What can a psychiatrist who died 60 years ago offer working-class struggle in the 21st century? Nigel Gibson’s Fanon Today: Reason and Revolt of the Wretched of the Earth (Daraja Press, 2022), an edited volume with contributors from Syria and Pakistan to Palestine and South Africa, suggests an answer: revolutionary healing.

Completed during the pandemic with its attendant amplification of inequity and trauma for the impoverished, this book is a product of the moment, and at 551 pages, unstinting in its coverage. Although it is organised into three sections, Fanonian Militants, Still Fanon and Fanonian Practices, the typology is not rigid. The sites in which Fanon remains relevant are geographically diverse, but one of the unifying features is that no matter where you look, Fanonian space is one of unfolding community power against the state. For that reason, communities are also frequently fenced in to contain the threat, and then pumped full of lead in order to eliminate it.

Consider, first, the fencing of intelligence. Wangui Kimari begins her chapter with Fanon’s observations about geography: “The colonised world is a world divided in two. The dividing line, the border, is represented by the barracks and the police stations.” Toussaint Losier’s fine chapter on Fanon’s relevance in United States prisons observes that it is not the holding of space that is the revolution, but the revolutionary consciousness that emerges dialectically from holding that space.

Related podcast:

The thinking that emerges from Fanonian revolutionary projects is counter-hegemonic and, therefore, a very real threat to state power. Frantz Fanon diagnosed the French colonial project in Algeria as an attempt to “decerebralise” the people, as Gibson reminds us in his outstanding chapter. When communities engage in the scientific analysis of their circumstances and respond with art, radio and politics, people reject colonialism. In Bairro Alto, Lisbon, lyric poetry and hip-hop battles are criminalised. In Los Angeles, police were terrified by the truce negotiated by gangs in Watts in 1992. As gangs laid down their arms, the police filled the vacuum with gunshots of their own, a mark of the panic that the recognition of community power engendered in the state.

For readers who expect to read Fanon on violence, Fanon Today makes clear that there has been a shift since Fanon first published the Wretched of the Earth in 1961. In the 21st century, the ongoing project of decolonisation is countered with violence not from colonial troops, but by domestic forces, whether of law enforcement or militias. The police are a constant threat. While they aim their guns at the bodies of militants, the ultimate target is communities’ capacity for thought, intelligence and wit. Postcolonial bourgeois forces respond with precolonial public policy, offering blood sacrifices to save their body politic.

Those fighting for justice have been systematic targets of police slaughter. From shack settlements in Durban to ghettos in Los Angeles, police violence is conducted as an exercise in teaching the impoverished that they cannot and should not try to think for themselves. In Cova de Moura in Amadora, Portugal, a space occupied by migrants mainly from Cape Verde, workers brought to construct a bridge the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar named for himself were penned in by wire fences and roads, and police shot one resident 54 times.

Global trauma

But bullets need not be shot constantly to be the source of permanent trauma. The threat of state violence is as real as chronic degradation and signs of the enclosure. Both Fanon the psychiatrist and Fanon the revolutionary matter in interpreting and then healing from the violence of colonialism.

Samah Jabr and Elizabeth Berger’s chapter is a hymn to the debt that mental health workers across the Global South owe Fanon when he pointed to colonial trauma and its complexes. Those who survive confrontation with the colonial state are often psychologically shattered by a trauma that will only be over with the end of the occupation.

Related article:

This trauma is global and made acute by the experience of Blackness, but Razan Ghazzawi’s critique of colourism complicates the idea that Black and white are simple categories. This is especially true when class and gender politics inflect the lived experience of militants on the front lines. Fanon would have had little time for authenticity politics.

Fanon the physician understood that the violence of colonial struggle is meted out in many different forms. Indigenous communities are more likely to die – and die by diabetes, homicide and suicide – than the settlers in their countries. Léa Tosold’s chapter, which locates Fanon in the struggles of the Munduruku people in the Amazon and which includes an analysis of the praxis of self-demarcation of territory despite fearsome state resistance, is particularly welcome. Readers wanting more on Fanon and Indigenous studies can head to Glen Sean Coulthard’s Red Skin, White Masks (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

The language of struggle

The Indigenous struggle around the world always involves the defence of ways of thought under occupation. In different ways, Losier and Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh share how incarceration was, for a few, a school of struggle because it was a school of language. Speaking Irish against the hegemony of the occupier’s English was, as one republican ex-prisoner put it, “a crucial part of our struggle against criminality and helped form our identity. We had to fight to learn and speaking it was a form of resistance. Every time we spoke Irish, we were telling our enemy that we were Irish republicans, protesting and struggling. We weren’t going to let them silence us … Irish was a weapon we used against the screws leaving them feeling totally frustrated and excluded. Our expression of identity left them feeling totally powerless. Knowledge is power and ignorance diminished their sense of power and control.”

This language has real healing power. In a number of studies, Indigenous-language use protects its speakers from smoking, alcohol abuse and diabetes, malaises that have colonialism as their vector. Such languages are under attack by colonial capitalism not least because of the grammar of intelligence and reciprocity that is undermined by colonial English. Perhaps the highlight of the book is a chance to see Fanon at work in the rearticulation of language in a dialogue between Gibson and a range of members of Abahlali baseMjondolo. In the dialogue, Fanon is discussed as a way of getting into the politics of movement building, as are the mendacities of “smart city planning”, conflicts over the role of religion and articulations of power within the ANC.

It is a rare privilege to see this kind of transcript of Fanon at work, particularly in an organisation that embodies so many of the ideas in the book. The language of Abahlalism defies the state: the government saw Abahlali as living in “informal settlements” or “slums”. Abahlali itself embraced the language of “shacks”, proud to be occupying and socialising land and housing, and affirming its right to the city. Abahlali’s insistence on its ability to think independently of the state was first met with accusations of a third force, disbelief by the state and the bourgeoisie that impoverished people might be able to think and write for themselves. And, as the threat of organised and intelligent activism pressed back against the state, it has killed dozens of people in response, all of which has left the movement traumatised.

Related article:

The road to healing will be long. No one pretends otherwise. Fanon himself understood the need to decolonise the process of healing. After trying his best to transform the psychiatric facilities at his practice at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Facility, Fanon left to join the liberation struggle in earnest. He died at 36 of leukaemia, but not before observing the colonial barriers to his own practice: “Behind ‘the doctor who heals the wounds of humanity’ appears the man, a member of a dominant society and enjoying in Algeria the benefit of an incomparably higher standard of living than that of his metropolitan colleague. Moreover, in centres of colonisation, the doctor is nearly always a landowner as well.”

It is entirely fitting that in this fine book, those engaged in the radical praxis of healing are movements that are subverting the institutions of private property as a path to an emancipated society. Fanon’s legacy today is kept alive in their struggle.