For Barney Rachabane, jazz was a way of life

Starting with a penny whistle as a child on the streets of Alexandra township, the saxophonist went on to leave an indelible mark on South Africa’s musical landscape.

Author:

18 November 2021

When the South African media finally notice the passing of saxophone hero Barney Rachabane on 13 November – at the time of writing, 36 hours in, only one newspaper has done so – they will no doubt foreground his 1987 participation in Paul Simon’s Graceland project.

For Rachabane, and many of the other South African musicians who featured in the project, it was Graceland that took their sound to international stages, audiences and collaborations; it was an important professional opportunity.

But it’s a big mistake to present that opportunity as what “made” them. Simon was led to those artists by shrewd local producers because they were already stars on South African stages. They were stars because they had come from the people, and created music that spoke from and to the people.

That was certainly the case with Rachabane, who was part of the generation that shaped the sound of modern South African jazz.

Rachabane was born in Alexandra township on 2 March 1946. His father was a bus-driver who also played piano. Alex, the first township to be established on the outskirts of Johannesburg, was proclaimed as a freehold location in 1912 and famed for its political activism and its total lack of streetlights, which earned it the title of “Dark City”. It was also home to some notable senior jazzmen, including Zacks Nkosi and Ntemi Piliso.

In the early 1950s, Rachabane was just one of dozens of small Alex boys who admired these bandleaders from afar, climbed on one another’s shoulders to peer at their performances through community hall windows, and eventually plucked up the courage to offer to carry their instruments – for a few cents, or just for the honour of walking beside them or sneaking into the show.

At the age of seven, Rachabane and two of his peers acquired penny whistles and became The Little Bunnies, a street corner band, whistling, as the late National Poet Laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile titled an essay, “for pennies”. The nickname “Bunny” followed Rachabane for a long time.

“No matter what your turn of mind,” wrote Kgositsile, “the lyricism and sometimes bluesy anguished happiness of this seemingly casual music touches your sensibility … sometimes robust, at times whirling, always brutally moving and demanding, [it] has all the ingredients of township life.”

Joining the life

By the time Rachabane was a teenager, both Nkosi and Piliso noticed his enthusiasm and talent and started to invite him, as he recalled, to play “at weddings. I was still at school so I could only play at weekends … In the townships, music was the life … the only way to play was to join up with the old guys and play alongside them to learn more.”

Rachabane’s heroes were American players on LPs, and national icons such as Nkosi and Kippie Moeketsi, “the nearest thing of everything I used to listen to on record. I always thought I want to be like that man … In the late 1950s, Selborne Hall, I would be in all those [Township Jazz] shows playing penny whistle and that’s where I would listen to Kippie’s beautiful playing behind the curtain.”

Rachabane was nonchalant about his own transition from penny whistle to alto sax and clarinet. “It was very easy; you don’t need anybody to show you. Just grab it and play it,” he told music scholar Chats Devroop.

But while it was true that several other penny whistle child stars, including “Little Lemmy” Mabaso, made the same transition, not all of them were, just a few years later, hanging out with the elite modern jazzmen of Johannesburg’s Dorkay House, experimenting with fast, risky home-grown bebop sounds.

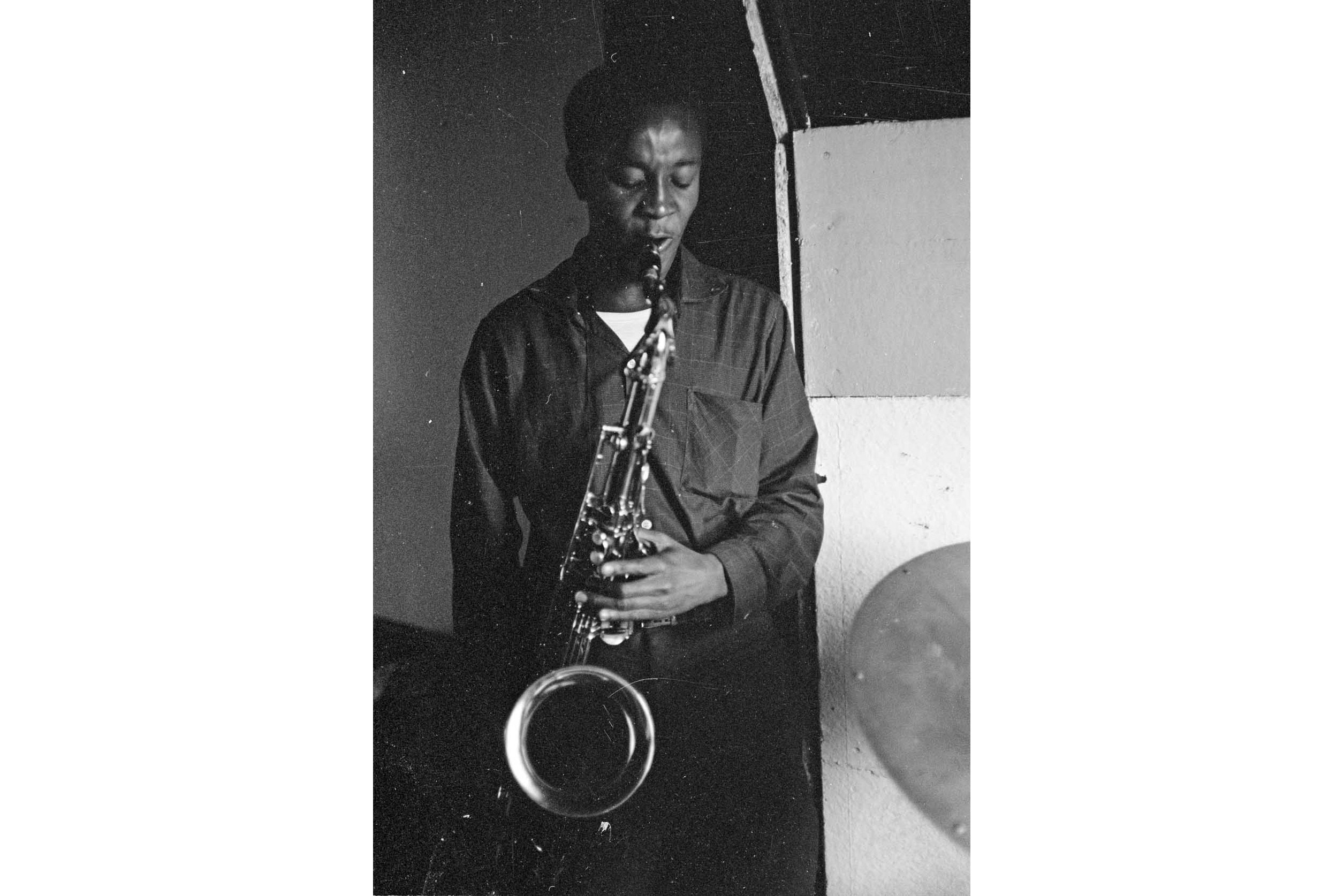

The photographs of that era show a still startlingly young-looking Rachabane jamming with his peers and elders, the cream of the scene: trumpeter Dennis Mpale, pianist Tete Mbambisa and more. By 1964, only 18, he was considered accomplished enough to deputise for his hero Moeketsi in drummer Early Mabuza’s Quartet at the Castle Lager Jazz Festival.

He went on to work with Mabuza’s Big Five, and with several bands led by Tete Mbambisa, including the Big Sound and the small group the Jazz Disciples in Cape Town, which he said he found a slightly more “laid-back” city than Johannesburg in terms of the enforcement of apartheid.

Rachabane featured in some of the landmark recordings of the late 1960s and 1970s, creating both intense modern jazz such as the Soul Giants’ I Remember Nick and music that nodded more towards popular trends. In his own group, Roots, with Mpale, Zacks Nkosi’s son Jabu and Sipho Gumede, he explored jazz fusion. He worked on the Beaters’ debut, Harari, recorded bump jive and even mabone (sax jive) with the Sound Proofs.

He was developing a distinctive saxophone voice and his own stage image, straight from the fashions of the Joburg township streets – often a checked shirt and almost always a poor-boy cap. From a player not much over five foot tall, the sax sound was startlingly big, rounded and warm, characterised by a ululating reed shout that, once heard, stayed in aural memory forever.

A homebody on tour

Life was harsh through the late 1970s and 1980s for musicians. Censorship, tight audience and stage segregation, curfews, violence and states of emergency meant players had to travel and take whatever meagre work they could find in whatever genre, or stay home, compose and starve. “The guys could not really make money,” the reedman said. He never disassociated himself from the struggle against oppression, attending the 1982 Medu Culture and Resistance Festival in Botswana.

But he loved his home and his family. “I felt the pain through apartheid,” he told Devroop, “but did not want to run away from it.” He described the time as one when he was “very militant” but “I didn’t go abroad. I just stayed here and accepted the whip … stayed here at home and played and practised.” Of those who did suffer exile, he commented: “I think they were very brave to do that.”

Rachabane recorded two more albums as leader, Blow Barney Blow in 1985 and Barney’s Way in 1989. In between came Graceland, a project he stayed with for 20 years.

That and time on the road with Hugh Masekela following the Botswana Techno-Bush recording gave him the opportunities to travel and interact with his American jazz peers he had previously lacked. Simon hailed him as “one of the most soulful saxophone players in the world; one of the best I have ever played with”. Rachabane recalled a conversation with the American reedman Michael Brecker: “[He] used to say ‘this is unique, man’. He never hears anybody in the world play the way we play. Even if you try to play the American tunes … you still have our flavour. We’re born with it … it’s just different.”

Touring was a mixed blessing. Rachabane told many journalists he still regularly got homesick and couldn’t wait to be back. And he did not idealise New York: “A very tough place to be. I could never in my mind imagine hustling in that place. Arrrgh! Very tough … You’ll see a guy sleeping in the park and he’s got his saxophone – street sweepers are jazz players – and people are cold…”

The international opportunities continued, including a 1990 partnership with pianist Darius Brubeck and bassist Victor Ntoni at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival with the Afro-Cool Concept. He displayed a different musical character in an intense, contemplative relationship with trumpeter Bruce Cassidy in Conversations. More recently, he got the opportunity to reunite with Mbambisa when the pianist toured a revisioning of his Big Sound concept including United Kingdom musicians. He would also pop up as a guest on South African stages, playing as well as, if not better, than ever and finally receiving some recognition for the role he had played in shaping that distinctive jazz sound at home and taking it to the world.

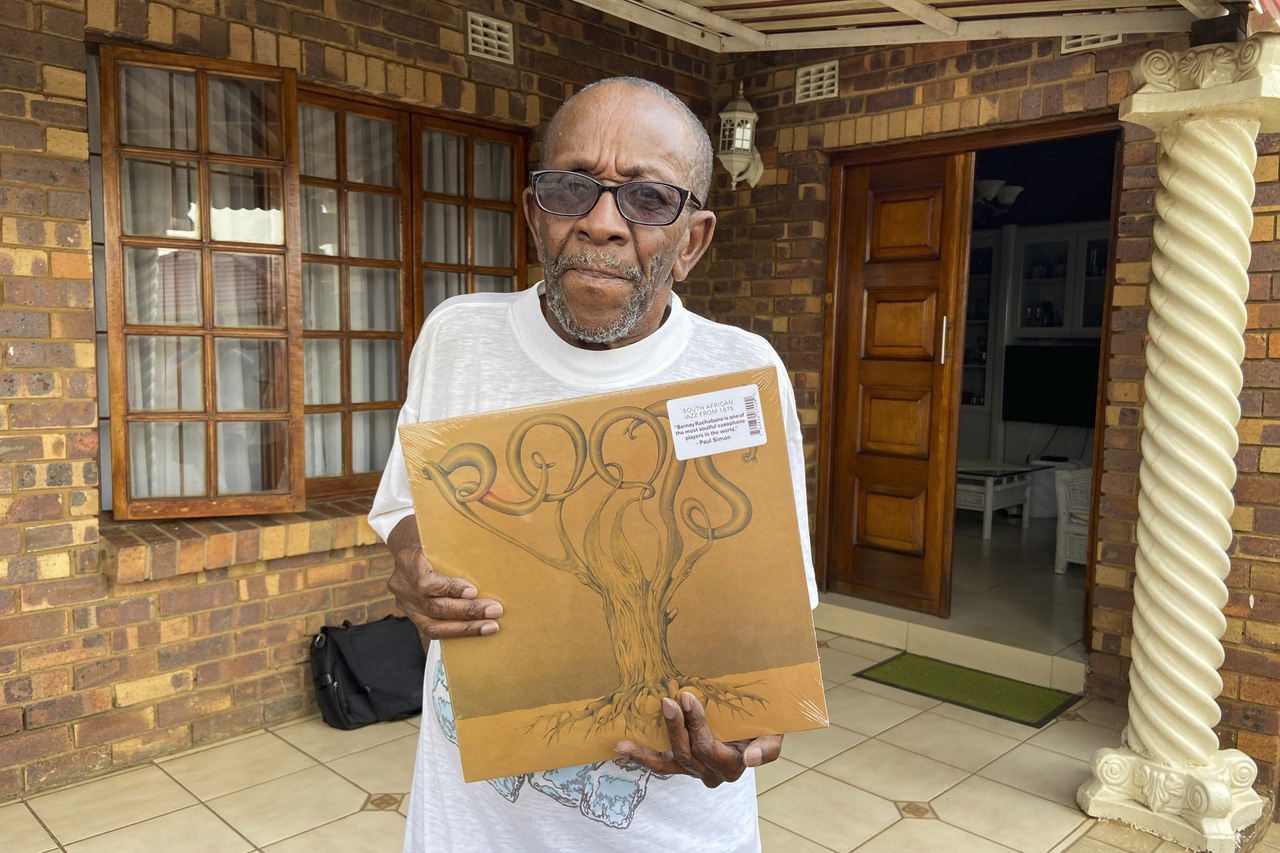

In late 2020, the Fredericksburg record label re-mastered Roots for reissue. The horns, relegated to the background on some tracks of the original, now sounded loud and clear. Rachabane was delighted the album was back in circulation, but archivist Calum MacNaughton of the As-Shams label recalls that he was more interested in talking about “his home and family”.

The saxophonist had worked hard to keep that together over the years, and it was his pride and joy: three daughters (of whom the youngest, Octavia, is a jazz vocalist) and a son, Leonard, also a saxophonist, who died tragically young. Now grandson Oscar continues the saxophone tradition. Rachabane had met his wife Elizabeth Nini when he was 14 and they had been together for 60 years. He told Devroop: “I still love her so much.” Elizabeth died on 30 July. Eyesight problems and his devastating grief at that loss contributed to his growing frailty this year.

In personality, Rachabane was very unlike the fiery Moeketsi he had so admired back then. He just quietly got on with his music work, with the fire confined to his sound, and was prosaic about his achievements. But he had regrets. He told me when I interviewed him that “the history is not written anywhere. There’s been albums and now you don’t even know what they were. The history of our jazz has been thrown away …”

Let that not be the case with his own, quite remarkable, life. Hamba kahle.