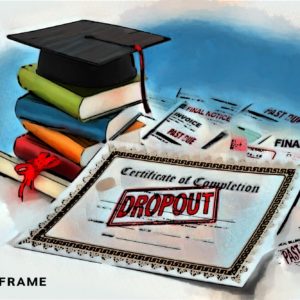

Financial aid schemes hinder graduates’ job search

Impoverished students suffer the consequences when the National Student Financial Aid Scheme fails to pay universities, which then withhold academic records.

Author:

12 April 2022

Millen Mndawe, 22, is among the thousands of students from the Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) who cannot access their academic records and graduation certificates because they owe the university money. This is despite qualifying for undergraduate funding from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS).

It is common for learning institutions to withhold qualification certificates if students have outstanding fees. But this practice makes it difficult to pursue further studies or to find work. Mndawe says she feels hopeless and stuck after the NSFAS failed to pay for her undergraduate diploma in human resources management between 2018 and 2020. “Eish! It is hard,” she says.

Her debt prevents her from accessing her third-year results. She knows, however, that she qualified to pursue postgraduate studies for an advanced diploma in human resources, even though she does not know the results of her assessments for her final undergraduate year.

Related article:

During the TUT graduation ceremony in July 2021, Mndawe was handed an envelope containing a statement of debt amounting to R40 771 and a letter of completion that says that she met all the “prescribed requirements for the awarding of the national diploma”.

When Mndawe asked, an NSFAS call agent said that her tuition fees had been paid. But TUT disputes this. To get her certificates and access her academic records, Mndawe must settle the combined debt for both her undergraduate and postgraduate studies, which comes to more than R70 000.

Prospective employers insist on graduation certificates, so Mndawe’s job applications are being rejected because she only has her letter of completion. “The only proof that I graduated are my graduation pictures on the wall,” she says, pointing at the pictures on the wall of her home in Phola, Mpumalanga. Mndawe will technically graduate with her advanced diploma in May but will not receive the actual certificate because of the debt.

Inequalities in higher education

In response to a parliamentary question, Minister of Higher Education Blade Nzimande said on 16 March 2021 that 106 494 students were blocked from receiving their qualifications between January 2010 and December 2020. They owe their respective institutions more than R10 billion. At TUT over the same period more than 11 000 students did not receive their academic records, and the total debt these students owe is close to R5 million.

“Historical debt affects largely poor students who have to move from villages to the city to access education,” says Nkanyiso Ngqulunga, an education activist with a background in law. “They face the costs of higher education and that of their living expenses. This reproduces inequalities … Those who can afford [it] can graduate and leave to get opportunities whereas poor students have to wait longer, or parade their poverty on social media looking for a good Samaritan to bail them out of their misery.”

Ngqulunga explains that the courts have ruled that law students can get admitted as practising attorneys even if their certificates are withheld. He adds that withholding qualifications exposes the inherent inequalities of higher education, which underlines the need for the “decommodification of education in this country”.

Related article:

Mndawe is desperate to find work and pleads on behalf of all the NSFAS-funded students with outstanding fees to be allowed access to their academic records and graduation certificates, so they have a chance of finding employment.

Ngqulunga insists that companies should hire people without graduation certificates if they can produce a proof-of-completion letter from their learning institution.

Mndawe has started saving up from her mother’s salary, who works as a cleaner. She deposits R500 a month into a bank account, and hopes to use the money to pay for the advanced diploma – but that is if the NSFAS pays her outstanding undergraduate debt. “Right now, I am stressing about the NSFAS failing to pay. On the other hand, I must also pay for my advanced diploma. I am still unemployed. It’s a lot.”

Related article:

Questions sent to the NSFAS regarding Mndawe’s outstanding fees were not answered, purportedly because the Protection of Personal Information Act (2013) prohibits sharing student information with third parties. “The allegations made against the NSFAS by the student through the media will have to be investigated and responded to with facts,” says the NSFAS spokesperson Kagisho Mamabolo. “Once we have concluded our investigation … we trust the student will share … the finding with you.”

TUT failed to respond to questions by the time of publication.

Mndawe received a call on 25 March from the NSFAS promising to settle the outstanding fees for her undergraduate diploma, but she is sceptical that the money will be paid. The financial aid scheme is yet to resolve the issue. “Once I see changes as promised by the NSFAS by 1 June, I will be able to comment on how getting my certificate will change my life.”

In the long term, Ngqulunga suggests that the government cancels student debt – or that “universities should enter into acknowledgement of debts with students by giving them certificates to look for jobs. No one benefits from withholding certificates. It is also arbitrary and disproportionately affects poor students,” he says.