Few secrets, much intrigue in insights from exile

This Sharp Read takes a look at International Brigade Against Apartheid, a collection of personal tales about the struggle for freedom with the emphasis on those who operated outside SA’s borders.…

Author:

3 February 2022

Remember the 1980s, when the international media were swarming all over South Africa, the dollars and krona flowed like wine, every local journalist had an overseas string, every non-governmental organisation had an offshore Santa, and a brave new world was just over the horizon?

Chester Crocker, Bruce Springsteen, “boycott the fruit of apartheid”, Free Nelson Mandela, the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) and the End Conscription Campaign, the comrades and the toyi-toyi, “talks about talks” … South Africa, now a neglected corner of the Global South, was in the eyes, ears and mouth of all the world.

International Brigade Against Apartheid – the title deliberately recalls the Republican volunteers who fought and died in numbers in the Spanish Civil War – conjures that heady, fleeting and long-lost age.

Subtitled Secrets of the People’s War That Liberated South Africa and edited by former Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) commander and Cabinet minister Ronnie Kasrils, it comprises 60-odd short personal recollections by pamphlet bombers, arms smugglers, buriers of dead letter boxes, safe-house providers, disinvestment and sanctions campaigners, pitch invaders and other non-South African auxiliaries of the anti-apartheid struggle.

Related article:

It also recalls an earlier, very different age when the outside world cared little about apartheid or actively approved of it, and when attempts to mobilise against South Africa amounted to the merest “germ of a movement”.

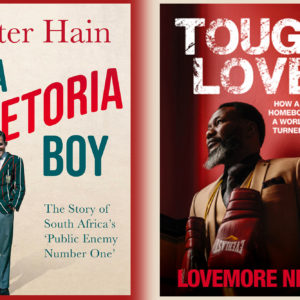

One of the book’s contributors, sports boycott leader Peter Hain, makes the point that international anti-apartheid solidarity “was bitterly hard fought and for most of … nearly four decades … we were in a minority”.

“Country by country voted in the United Nations to condemn apartheid but then traded with and armed the white state; ruling elites in predominantly white Commonwealth nations like Britain, Australia and New Zealand forcibly opposing campaigns to defeat it.”

Another contributor, the former secretary of the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid, ES Reddy, describes how when he tried to raise the issue of apartheid after the Defiance Campaign in the early 1950s, his boss at the UN Secretariat told him it was an internal issue, impugned his lack of neutrality and shifted him to research on the Middle East.

Illustrating the overwhelming risks and difficulties in the early years is Kasrils’ account of the Aventura, a former United States government vessel bought with Soviet money in 1971 in the hope of landing MK guerillas on the Transkei coast.

Engine trouble crippled the ship soon after it set out from Somalia and it limped back to port. Its crew, Greek exiles living in Poland, were replaced by British seamen. A second attempt was made and aborted when the Aventura’s engines failed yet again.

The slapstick ended in tragedy. When the MK fighters were rerouted through Swaziland and Botswana, they and the reception party, including the Greek citizen Alex Moumbaris and his pregnant French wife, Marie-José, were betrayed and arrested.

The tide turns

And yet … by the late 1970s there was such burning anti-apartheid sentiment in the US that 17 states and 60 cities had disinvested from South Africa. By 1986 the Congress could overrule Ronald Reagan’s sanctions veto by passing the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act.

The question of how apartheid became a cause célèbre in the West when other similar campaigns have struggled to get off the ground – one thinks of the trifling support for the beleaguered Palestinians – is an important one.

Hain emphasises the unique zeitgeist, with its “sit-ins, anti-Vietnam War protest, the Paris 1968 revolt and the American antiwar and civil rights movements”, and a youthful culture of direct action and confrontation with the established order.

The biographical details of many anti-apartheid campaigners in International Brigade points to their tender years. One of them writes: “We started in 1986 when we were young and raring to go, in our twenties and thirties …”

Related podcast:

It was an expansive time, quite unlike the present, when the grim austerities of post-war reconstruction in Europe had given way to emancipatory and experimental thinking on all fronts.

It is interesting to note from the biographical details how many of the international collaborators moved on to humane professions such as development planning, low-income housing provision and alternative psychotherapy. They acted out of principle, but were also drawn by the prospect of adventure. All in all, they seem to have been a brave and high-minded lot.

Also underscored is the broad appeal of the solidarity movement – rather than being a narrow preoccupation of the political Left, it was embraced by many ordinary people. “Church clerics criticised apartheid from the pulpit regularly, writes Sean Hosey, “and middle-class housewives shunned South African fruit in the supermarkets … Everyone had heard of Nelson Mandela.”

Refreshing detail

International Brigade is not “big history” seen in panorama – in its pages, historical events are refracted through the many small prisms of individual lives. Despite the subtitle, the collection contains very few heart-stopping secrets. What it does quite often, however, is pencil in the detail.

At the time, the 1982 Koeberg bombing was a vague, ill-covered event, so the specifics of the operation – how Rodney Wilkinson smuggled limpet mines into the plant, for example, and later pedalled to safety across the Swaziland border on a bicycle – hold interest even at the distance of three decades.

Another large occurrence seen through a chink is Belgian-born Oscar Marleyn’s account of reconnoitering the oil pipeline from Durban to Sasolburg, maps and camera in hand, for MK. He advised that the line ran underground or was too heavily guarded, and that “an MK unit would be too exposed if it intended to do more than explode a device”.

The alternative target, and strategic approach, appear to have been Sasol 1 and Natref, targeted with limpet mines some months later in the spectacular curtain-raiser to the decade of “total onslaught”.

Marleyn also describes loading the 2.5m artillery piece apparently used in the Voortrekkerhoogte rocket attack beneath a Ford pickup truck. Carried out at night in the backyard of his Maputo home, the job caused “clanging and banging [that] could be heard three or four houses away in this quiet residential suburb … To my surprise nobody came to check.”

Although described in too much repetitive detail by too many participants, the most impressive covert mission detailed in International Brigade is Operation Laaitie, also known as African Hinterland. Posing as an overland safari operation, a custom-built Bedford truck carrying European tourists infiltrated 40 tonnes of weapons into South Africa between 1987 and 1993, without a casualty.

Wilkinson, in exile in London, designed the vehicle, which cost the ANC £80 000. The weapons were buried in marked DLBs (dead letter boxes) by an internal network that relied on many foreign sympathisers, for recovery by MK soldiers.

The ingenuity and efficiency of the operation, and the daring and idealism of the internationalists who joined it as drivers, porteurs de valises (suitcase carriers) and storers and distributors of arms, are not in question. What is less clear is whether African Hinterland contributed much to bringing down apartheid.

The Pretoria Minute suspended the armed struggle midway through the operation, in August 1990. How many of the cached weapons were actually fired or detonated in anger in the war against the South African state and its agents?

Open to question

International Brigade generally avoids nationalist triumphalism and the rewriting of history, but is not entirely innocent of these vices.

There is the remarkable claim by Anti-Apartheid Movement activist Christabel Gurney that “the Frontline states of southern Africa stood firm in the face of armed raids and the fomenting of civil war by South Africa’s armed forces”.

Has Gurney not heard of the Nkomati Accord? Of the military putsch in Lesotho that toppled Leabua Jonathan? Of the secret security pact between the Swazis and PW Botha’s government?

Because Mozambique’s own revolution was threatened by South African-sponsored mayhem, Samora Machel can be forgiven. But the Swazi security forces and traditionalists of the Liqoqo, who snatched the reins after King Sobhuza’s death, had no excuse for their craven kowtowing to Pretoria.

Zimbabwe’s role also comes under scrutiny in Kasrils’ book, through the spicy juxtaposition of two articles that essentially contradict each other.

Arguing for “unbreakable cultural, political and economic ties” between Black South Africans and Zimbabweans, Fidelis Hove concentrates on the relationship between MK and the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (Zipra), the military wing of Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu), in the 1960s, and particularly their joint Wankie and Sipolile operations.

Far more controversially, he goes on to claim that after Zimbabwe’s independence in April 1980, “the bond between the Zimbabwean and South African liberation movement grew”.

A different reality

A very different picture is painted by former Zipra high-up Jeremy Brickhill. He writes that at a conference in 2019, the late Zipra commander Dumiso Dabengwa noted the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) government’s open hostility to the ANC and that “they were assisted in their efforts to block the ANC-MK presence in Zimbabwe by former Rhodesians and the many South African agents operating in the Zimbabwean security services”.

Facing “a wave of terror unleashed against us [Zapu and Zipra] by the Zanu government, we continued to provide support and assistance to MK and underground ANC operatives in Zimbabwe”, he writes. This included hiding MK fighters, providing safe passage, and intelligence and military cooperation.

Brickhill says he personally recruited Wilkinson into MK after he and his partner in sabotage, Heather Gray, tried to contact the organisation’s representatives in Zimbabwe to hand over top-secret Koeberg documents.

When the South Africans learnt that MK fighters were secretly integrated into Zipra units, he alleges, the Zimbabwe government ordered their removal to Zambia. “We made a show of removing some of them but others were hidden and provided with assistance … to establish themselves in our towns and villages.”

Related article:

He also makes the explosive claim that the government’s discovery of arms cached for MK, “with the direct involvement of apartheid agents”, was used to put Dabengwa and other Zapu-Zipra leaders on trial for treason and unleash the Gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland.

Zanu-PF’s hostility seems to have been fuelled by a volatile mixture of ideology, fear of South African reprisal and ethnic suspicion. The spotlight International Brigades puts on it, and on Zipra’s continued dealings with the South African underground in defiance of Robert Mugabe’s government, is its most piquant disclosure.

But it has to be said that swathes of the book are already in the public domain. And the selection of contributors sometimes seems off-centre – Basque solidarity hardly merits inclusion, and Barney Pityana’s article about Black Consciousness seems to have been solicited largely in the spirit of fairness to an alien political tradition. Far from emphasising international camaraderie, the Black Consciousness watchword was “Black man, you are on your own”.

Flawed perspectives

Perhaps one’s main reservation is that books of this kind encourage the perception that the externalities of the anti-apartheid struggle, and particularly its military aspects, were paramount and events inside South Africa peripheral, or an extension.

It is disconcerting that the 345 pages of International Brigade contain just two or three references to the United Democratic Front (UDF) and possibly more mentions of the South African Congress of Trade Unions, the ANC’s internally defunct trade union wing, than the Congress of South African Trade Unions.

Of course, global solidarity and money were vital to sustaining organisation and bolstering morale inside South Africa. Horst Kleinschmidt reveals that the London-based International Defence and Aid Fund, for example, channeled £200 million in legal aid and assistance to the families of jailed, detained and executed activists, sourced from 56 governments. Up to 65% of this came from the Swedish government, which pumped more than R6 billion into non-military resistance between 1972 and 1994.

Related article:

In addition, MK’s “armed propaganda” was a great symbolic inspiration to the youthful insurrectionaries who manned the barricades from Worcester to Sekhukhuneland.

But to suggest that the township militants acted under ANC or MK direction is a conspiratorial delusion worthy of the South African Institute of Race Relations – all the indications are that they rose spontaneously and that the vast majority were unarmed.

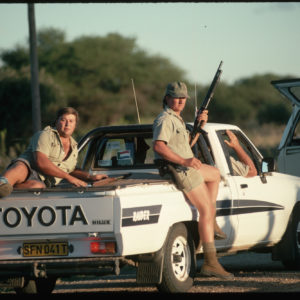

Equally, it is clear that in purely military terms, the South African state could have held out against MK’s guerilla campaign until, to use Jacob Zuma’s phrase, the return of Jesus.

Two forces principally drove Pretoria to the negotiating table: the tightening noose of capital starvation – the product of international sanctions and disinvestment – and rising turmoil at home, to which the UDF and the trade unions in the MDM were pivotal.

Related article:

These fuelled each other in a cycle, but the main direction of the current was outward rather than inward. Gurney rightly observes that “the explosion of solidarity in the 1980s was above all a response to the growth of resistance within South Africa. The formation of the … UDF in 1983 and the insurrection in the townships in 1984-1986 changed the potential for anti-apartheid action in the international community.”

Kasrils is a principled and sincere man, as his willingness to stick his neck out over the Palestinians and the sins of Jacob Zuma makes clear. But he has a broad streak of revolutionary romanticism that inclines him to a fascination with things that go bang and the cloak-and-dagger side of warfare – disguises, codes, dead letter boxes and messages written in lemon juice.

One of the founders of MK, he also spent 27 years out of the country. One cannot help feeling that the perspective of International Brigade is one of a military-minded, long-term exile for whom “the people’s war that liberated South Africa” was centrally about what happened in Lusaka, Moscow and London.

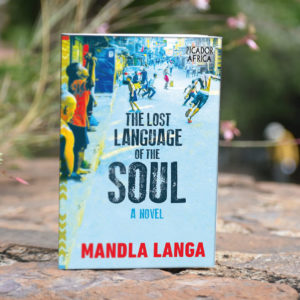

International Brigade Against Apartheid: Secrets of the People’s War That Liberated South Africa is published by Jacana.