Fans demand the PSL open stadiums

The closure of stadiums has left supporters frustrated. And those who depended on stadium attendance to make a living have been left struggling.

Author:

11 March 2022

Mapaseka Moabelo, 52, fights back tears as she explains how the ban on supporters in football stadiums has affected her and her livelihood. Before the Covid-19 pandemic and the restrictions it came with hit, from March 2020, Moabelo sold braaied meat at football matches to make a living.

“Last year, I had to move out from where I was renting and had to return back home because I could not afford rent,” the mother of two children and grandmother of two said. “The money I made, I used to support my children and pay for my policies. But currently I don’t have anything. Last year, I also had to break up with my partner because I was used to making my own money but now, we were both stuck at home without any money coming in.”

Moabelo, who had been renting a house in Dobsonville Extension 3 since 2000, moved back to her parent’s home in Extension 2 of the township in Soweto. She is among the many people who have been hit hard by the closure of football stadiums, which have not been opened despite the government allowing a portion of supporters to attend sporting events. Meanwhile, concerts and other entertainment facilities are now operating without restriction.

It is because of the plight of people like Moabelo, and the inconsistency with which large-gathering events are treated, that the National Football Supporters’ Association (Nafsa) organised a peaceful march on 5 March.

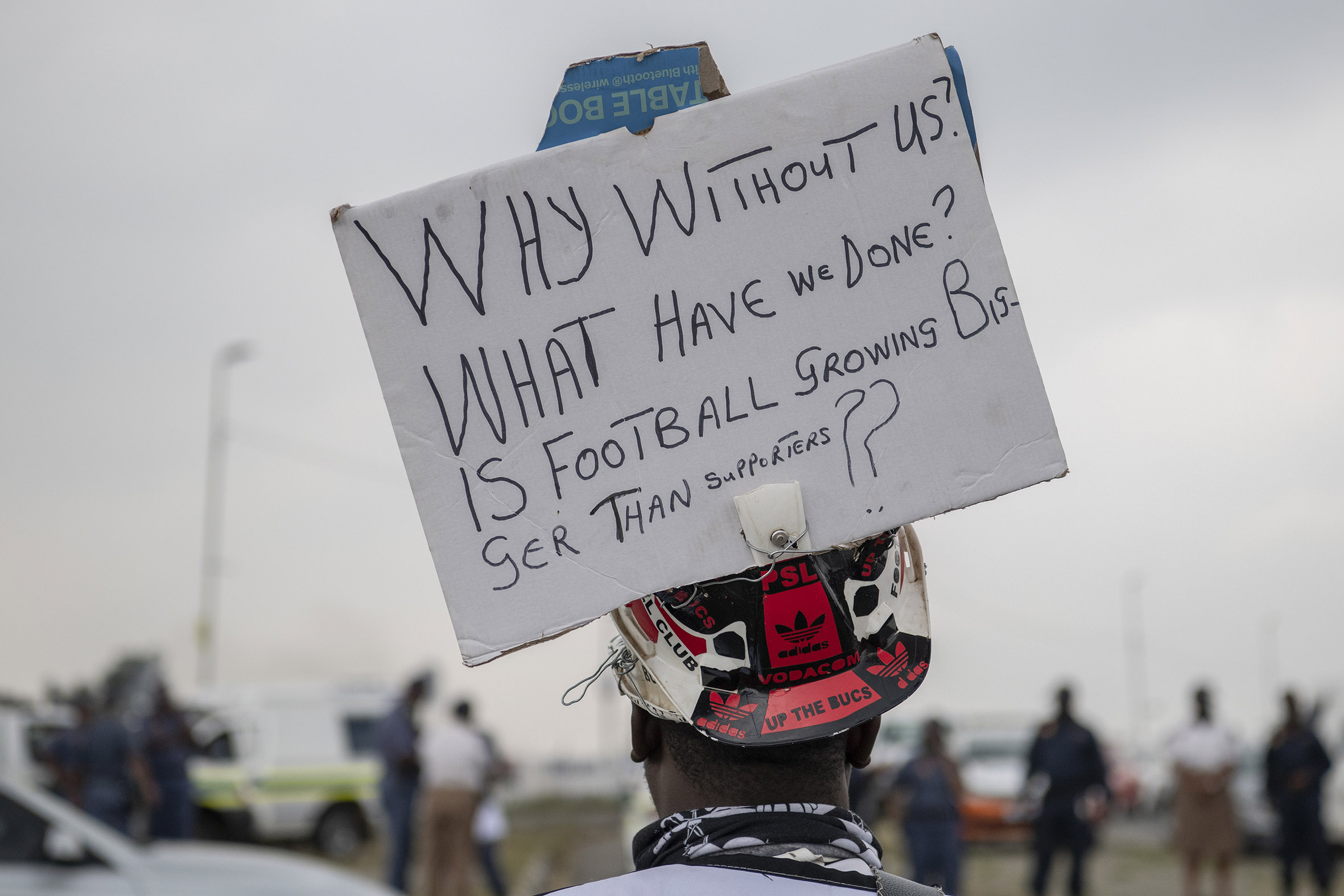

On the day of the march, a cacophony of noise around Orlando at noon fuelled “derby day” in what would otherwise have been another silent Soweto Derby between rivals Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates. A handful of football lovers, dressed in the regalia of their favourite Premier Soccer League (PSL) clubs, convened at the traffic circle on the Soweto Highway, a stone’s throw away from Orlando Stadium, which hosted the 175th Soweto derby.

These supporters sang in solidarity, recreating the nostalgic moments that they used to savour when they were still allowed at stadiums. That is before Covid-19 took away that euphoria.

Motorists, including actor and comedian Kenneth Nkosi, a staunch Pirates supporter, could not help but join in on the act. They hooted and signalled the sign of their beloved clubs – either the skull and crossbones for the Sea Robbers, the love and peace sign for Chiefs and the seven for Mamelodi Sundowns.

‘Vul’ amasango’

But this gathering was not in honour of the most sought-after fixture in the country’s sporting calendar. The placards said it all: “OPEN UP THE STADIUMS! VUL’ AMASANGO!”

Even though the government has allowed sporting bodies to host a maximum of 2 000 supporters owing to Covid-19 restrictions, the PSL is still played behind closed doors. The league argues that opening up to only 2 000 supporters would see clubs operate at a loss because of the costs of hosting a match with supporters.

Nafsa executive committee members, who were geared up in personalised jumpsuits, led from the front in the march.

“Nafsa was founded in 1992. But it was amalgamated in 2012 to a three supporters’ group that was facilitated by Safa (the South African Football Association) to actually form the name Nafsa,” their acting CEO Siyabulela Loyilane said.

“The whole idea of Nafsa was to ensure football supporters unite behind one cause and purpose. And that is to support football.”

Unlike her colleagues who were all in white regalia, Loyilane stood out in a green jumpsuit that had an orange collar and ankles. In her pinkish cropped braids and white sneakers, she exuded confidence. She was the image of a confident leader as she fearlessly stood on top of a jersey barrier, the concrete barricade used on highways and in construction sites, to address those attending the march.

“It’s a great experience, I had never organised a march before. This was the first time,” said the holder of a masters’ degree in football and business administration from the Sports Business Institute of Barcelona. “Having to go through the compliance process and reach out to the people and say ‘let us be peaceful’ wasn’t easy, but [it was] fulfilling.”

Nafsa is the second organisation to picket for the reopening of stadiums. The EFF led the motion in January, picketing outside the offices of the Minister of Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture in Pretoria. And it is there that Loyilane joined forces with the EFF whose members in turn came out in numbers in Orlando.

“As young as I am and as a woman, I think people have given me respect because I am a football administrator. I know what I am doing in football. So, I am hoping that this war of getting supporters back to the stadiums will be won soon,” she said.

Football bodies go AWOL

But not everyone is as hopeful as Loyilane. That there were no officials from all the three entities – the PSL, Safa and the office of the minister of sport – to receive the memorandum came across as an insult. Only heavy security welcomed the protesters at Orlando Stadium.

Most of the blame was laid on the PSL, given that they had promised Nafsa to “send officials who’ll receive the memorandum on their behalf”.

Loyilane was not discouraged. “I am actually not disappointed because with the PSL we’ll actually deliver the memorandum because the channel of communication has been opened,” said an exhausted Loyilane in the aftermath of the protest.

“But it’s disappointing that we haven’t heard from the mother body, even though at times they’ll feel that I am fighting with them. I am not. It’s the frustration in me. And it is also about carrying the hopes of people on my shoulders.”

Safa said the PSL will have to consult with the office of the minister of sport if they want to open stadiums to full capacity as the amended regulation 69 of the Disaster Management Act permits 2 000 fans at outdoor sporting events. The organisation said local football, especially the matter of fans in stadiums, is beyond their control. For international matches, Safa has stuck to the law and allowed only the permitted 2 000.

There were, however, nervous moments for the organisers of the march as they feared that fans might throw missiles at the team buses when they arrived. But to their awe, the Pirates bus was welcomed with a round of applause. However, Chiefs’ luxury bus did not receive the same welcome. The fans surrounded their bus, resulting in law enforcement officers dispersing them with a stun grenade.

Chiefs went on to win the match 2-1.

“We lost the league two seasons ago because we were not there [in the stadium]. If we were there, I am telling you that the draw [to Baroka on the final day of the season] would not have happened. Even now they are not playing well because we are not there,” said Manelisi Kubayi, a Chiefs fan.

Kubayi’s love for football runs deep. She’s been attending live matches for close to 26 years, having started with the 1996 Africa Cup of Nations final at the FNB stadium.

“We are tired of sitting at home, doing nothing. We love football,” the passionate Amakhosi supporter said. “If you don’t have money for DStv you can’t watch your team. I am not working, that means I am unable to watch my team.”