Fake it, then make it: How con artists capture us

The popularity of shows such as ‘The Tinder Swindler’ and ‘Inventing Anna’ show the links between late capitalism and the grifters who use the allure of wealth and success t…

Author:

14 March 2022

Brothers Raees and Ameer Cajee promised patrons they could make small fortunes off Bitcoin using their company, Africrypt. But in 2021, the brothers fled South Africa, claiming criminals had hacked the platform. According to angry investors, they fled with $3.6 billion in Bitcoin. In Gauteng, a man named Jacques Arthur Malot posed as a Blue Bulls rugby player on dating sites. The women who initiated relationships with him were subjected to extortion, assault and theft – some even left the country in fear. School teacher Vindra Moodley told her employers in KwaZulu-Natal that she had been diagnosed with terminal ovarian cancer and only had months to live. Her friends and co-workers rallied to support her. The cancer was fake, but she used it to extort almost R2 million from the school.

These people are all con artists who use a false image to extract money, status and sympathy from their targets. The scam is insidious because it relies on victims voluntarily handing over money or support. The con artist’s weapon is people’s dreams. They exploit the desire for love, wealth or adventure for personal gain, leaving a trail of broken hearts and empty bank accounts.

Con artists have become an on-screen phenomenon. Netflix documentary The Tinder Swindler centres on Simon Leviev (born Shimon Hayut), who claimed on Tinder and Instagram to be the super wealthy son of an Israeli diamond billionaire. After luring his victims with lavish meals at five-star restaurants and trips on private jets, he would discuss building a life together. Once he had their unwavering trust, he would claim that he was being hunted by shadowy enemies, using this story to extort money and credit from his dupes. True to (patriarchal) form, Leviev now claims that his scorned lovers are sullying his good name and that he is a “perfect gentleman”, even in the face of overwhelming evidence.

Related article:

Another Netflix series, Inventing Anna, stars Julia Garner as the “Soho grifter” Anna Sorokin, whom New York Magazine writer Jessica Pressler first brought to the public’s attention. Pretending to be a wealthy German heiress, Sorokin gained access to the New York art scene and Wall Street investors, using the cover and appearance of wealth to live a lavish life of hotels, yachts, designer brands and international travel. Sorokin, who received a four to 12-year prison sentence for fraud, targeted the elite and showed no remorse for her schemes – she even hired a personal stylist to ensure her criminal trial was fashion forward.

As shown in the Netflix series, her social circle included other notorious con artists. Billy McFarland, the organiser of fake credit card company Magnises and the fraudulent luxury Fyre Festival in 2017, was once her roommate. She also partied with “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli, who raised the price of life-saving drugs while defrauding his investors.

Both The Tinder Swindler and Inventing Anna expose the links between class aspiration and identities constructed on social media platforms. The con artists used Instagram to convey an image of material wealth, the currency with which they bought people’s trust and respect. From relatively humble backgrounds, they used subterfuge to parachute into the spaces of the super rich.

Snake oil salesmen

Other con artists are more focused on domination over others. The chilling documentary series Puppet Master: Hunting the Ultimate Conman, released in January, shows how Robert Hendy-Freegard used fabrications about being an MI5 agent to insinuate himself into the lives of his victims. Using lies, emotional abuse and coercive tactics he estranged them from their families, effectively turning them into prisoners in their own homes. The documentary shows a David Lynch-style nightmare of cruelty and gaslighting taking place behind the placid facade of middle-class homes.

Many documentaries tread a fine line between romanticising the exploits and fabrications of con artists and condemning their criminal behaviour. But Puppet Master shows the devastating personal and financial harm they can cause.

Historically, con artists have also been known as grifters or snake oil salesmen, referring to the selling of fraudulent products. Capitalism has long produced criminal entrepreneurs prepared to tell lies for a quick buck. In the early 19th century, Scottish adventurer Gregor MacGregor convinced European investors that he had exclusive control of a territory in South America called Poyais. But instead of a bustling settlement, Poyias did not exist, and many of his victims who came to live in the promised utopia died in the jungle.

Related article:

One of the most enduring cons is the Ponzi scheme, which uses money from new investors to pay off existing ones, a practice Leviev used to finance his fake billionaire lifestyle. It derives its name from Italian Charles Ponzi, who ran a scheme in the early 1920s that extorted almost $200 million dollars (in 2022 currency). Ponzi schemes have only become more popular over the past century.

Financier Bernie Madoff was arrested for running one that amounted to $64 billion in 2008. Madoff was not a marginal figure but a Wall Street insider. While the extent of his crimes was extraordinary, it reflected the wider culture of casino capitalism and wild speculation in the finance industry that triggered the 2007 financial crisis.

‘Hell-bent on the high life’

The personal psychology of con artists has been of particular interest to writers and filmmakers. Crime noir author Jim Thompson wrote The Grifters, about mother and son con artist duo Lilly and Roy, in 1963. But it gained wide exposure after it was made into an acclaimed 1990 movie starring John Cusack and Anjelica Huston. Both the novel and film end with Lilly accidentally killing her son, crying as she leaves with his stolen money.

Tom Ripley, a more urbane con artist, is the protagonist of five novels written by Patricia Highsmith between 1955 and 1991. An orphan obsessed with gaining entry to the world of the wealthy jetset, Ripley uses murder and art fraud to finance a stylish lifestyle. European and American filmmakers have adapted the books a number of times, attracted by the frisson between sunny Mediterranean locales and the shadowy world of psychopathology.

Related article:

In both the Highsmith books and films – including 1999’s The Talented Mr Ripley, starring Matt Damon – the audience is seduced into feeling sympathy for the character, especially when he is in conflict with rich snobs and boorish criminals. In a similar way, Sorokin has become a folk hero because she tricked the idle and credulous rich.

But the con artist has something of a reptilian world view – they are cold-blooded. Ripley wants social respect; he wants to be perceived as a man of wealth and taste, and he will murder anyone who stands in his way. As the cover blurb on one of the early paperback editions has it, he is “hell-bent on the high life”. His desire for status contrasts with a misanthropic world view that sees people as “marks”, disposable pawns to be used and abandoned. In the final summary, the con artist is a predator who views society as their prey.

Summiting success

Much of the commentary on The Tinder Swindler and Inventing Anna focuses on how the image-conscious culture of social media encourages fake identities. But this technology exists against the backdrop of neoliberalism, with its Darwinian ideology of competition and wealth accumulation at all costs. In this culture, dishonourable or dishonest practices are now called “hustling” or “grinding” – the ends of more money and power are seen to justify the means.

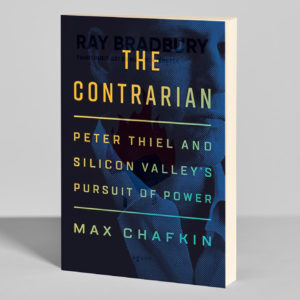

This attitude pervades the top of the financial pecking order. Elizabeth Holmes became the toast of Silicon Valley as a young chief executive whose company, Theranos, had supposedly invented a new way to test blood. But as shown in HBO documentary The Inventor (2019) and in upcoming dramatised miniseries The Dropout, despite raising almost a billion dollars in investment none of the company’s testing equipment actually worked. Holmes capitalised on the modern cult of the chief executive, in which plutocrats such as Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos are portrayed as geniuses rather than cut-throat businesspeople who have learned to game the system to their benefit.

Related article:

Ultimately, con artists flourish in a society that rewards ethical delinquency. Financial fraudster Jordan Belfort gained notoriety when Leonardo DiCaprio played him in the 2013 Martin Scorsese film, The Wolf of Wall Street. The film’s unflattering portrayal of him did nothing to stop the former convict, who rebranded himself as a business advice guru and headlined Success Summit South Africa in Johannesburg in 2014. Similarly, Leviev is now trying to capitalise on his notoriety by charging $20 000 to make appearances at nightclubs. Our culture permits these kinds of reinventions because of the way society views and treats white men.

But in their dishonesty, con artists reveal the truth about capitalism. Rather than through hard work or perseverance, the way to acquire a fortune is subterfuge, class power and exploitation. In an increasingly unequal and chaotic world, the myth of meritocracy is perhaps the greatest scam of all.