eSwatini Parliament starts to push back

Even as eSwatini’s Parliament shows some life, with lively debates that have led to the withdrawal of some of the regime’s bills, it remains an undemocratic institution under the king’s absolute co…

Author:

19 April 2021

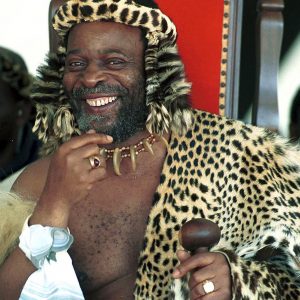

King Mswati III turns 53 today. Fresh from Sherbone School in Dorset, England, he ascended the throne at just 18, inheriting a system carefully built by his father, King Sobhuza II. Over the years, he has exercised control over the country, routinely quelling dissent and populating institutions with people agreeable to him and his policies across all three spheres of government.

Now, 35 years later, one institution – Parliament’s House of Assembly – is showing signs of independence, vigorously debating the government’s bills and notices to the point of rejecting some. But there is no official opposition in the house, owing to there being no political party representation. Instead, some members of Parliament (MPs) have formed a collective akin to one.

Radical MPs have steadfastly opposed some of the government’s laws and positions, but they are few and have had little support and impact on decision-making. This could change, though, as the number of MPs who have organised themselves into an effective coalition has progressed and they are critically debating bills, raising motions and defeating many of the government’s positions.

A history of rule

eSwatini became an independent state in 1968. Before then, it had been many things under settler rule.

After successive white administrations, the country became a protectorate of the South African Republic, under Boer rule, in 1894 through what was called the Third Swaziland Convention. With the British the victors of the South African War in 1903, it became a British protectorate and would remain a colony of Britain until independence.

Under a constitution drafted and implemented by the British, Swaziland became a democracy, with parliamentarians voted for through their political parties, for just four years. In April 1973, Sobhuza II – who had become king after independence, having been designated paramount “chief” in 1922 by the colonial government – declared a state of emergency, abolishing the independence constitution and dissolving the house of assembly. He would rule by decree until 1978, the year the country’s first general elections were held and a new constitution introduced, effectively banning political parties from participating in the political system.

King Sobhuza II died in 1982, leaving behind an electoral system called Tinkhundla. Under this system, one representative would be elected to Parliament from an administrative division (called inkhundla) created by combining a number of imiphakatsi governed by traditional leaders. For the purposes of elections, usually three imiphakatsi would combine to form a constituency, from which one MP would be elected. The system started with just over 40 tinkhundla. The number went up to 55 years later and is now at 59, after some constituencies were deemed too big and further divided.

Related article:

It is this electoral system that King Mswati III inherited along with his throne in 1986. It is a system he has presided over, as an absolute monarch, for many years. And it is a system that the country’s 2005 Constitution further strengthened.

Section 94 of the Constitution, for example, empowers the king to appoint 20 of the about 31 House of Senate members “in his discretion after consultation with such bodies as [he] may deem appropriate”. Then, once constituencies have sent their representatives to the House of Assembly, Section 95 prescribes that the king add 10 of his own. The constitution of the houses makes it his Parliament.

A significant year

Except for episodes of protests and futile outspokenness by some MPs in past parliaments, there has never been a serious opposition coalition in the House of Assembly – at least nothing organised and sustained. Suspect decisions have been taken and controversial bills passed into law by past parliaments with little opposition from inside the house. Then came 2020.

Progressive MPs in the house rejected at least two bills and one legal notice last year, sending them back for further consultations.

In June, the house was to pass the Opium and Habit-Forming Drugs (Amendment) Bill into law. It was a bill prepared in haste by the Ministry of Health and presented by Minister of Health Lizzie Nkosi. Deputy speaker Phila Buthelezi was in favour of passing the bill, as was attorney general Sifiso Khumalo, an ex officio member of the house. The minister claimed that the bill, if passed into law, would open the cannabis industry to eSwatini citizens and help revive the country’s ailing economy.

Related article:

There were reports, however, that an American company called Stem Holdings had already received preliminary approval, and would soon be granted a monopoly licence to farm and process cannabis and industrial hemp in the country. The cannabis bill would be the instrument to put a stamp on it all.

A group of MPs, led by Bacede Mabuza of Hosea Inkhundla, rejected the bill. A select committee led by Lobamba Lomdzala MP Marwick Khumalo had not conducted satisfactory consultations, said Mabuza, who suggested that the health ministry’s portfolio committee take over the process. Members of the house then voted overwhelmingly with Mabuza, rejecting even Khumalo’s select committee report on the bill.

A bill to tackle cybercrimes

In August, the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology published the Computer Crime and Cybercrime Bill in the government gazette. With Minister of Information Princess Sikhanyiso (King Mswati III’s daughter) on maternity leave since November 2019, it fell on acting minister Manqoba Khumalo to table the bill.

Among other things, the bill sought to criminalise sharing fake news on any medium, especially social media, with some offences carrying a fine to the tune of R10 million.

It was seen by many to target some of the independent and online news sites that are now popular among eSwatini citizens. Prominent among them is Swaziland News, a site that publishes investigative stories about even the most powerful in the country, including the royal family. The police detained editor Zweli Martin Dlamini after he published two stories about the king in early 2020, and confiscated his laptop and other devices. The police later said they were investigating him for suspected sedition.

Dlamini fled to South Africa and continued to publish stories, some about Princess Sikhanyiso. The bill came in the wake of this and commentators saw it as a politically motivated piece of law.

Related article:

Mlungisi Makhanya, leader of the banned People’s United Democratic Movement (Pudemo), said the bill was laughable. “The cybercrimes bill that you are talking about, I want you to check the Zimbabwean bill. Word for word. Those guys, they literally plagiarised and copied the Zimbabwean bill, section by section. They went and took [Emmerson] Mnangagwa’s bill and only replaced Zimbabwe with eSwatini.

“We are not resolving challenges that are potentially facing Swaziland. We are getting inspiration from other dictatorships to try and strengthen [a] tin-pot dictatorship here.”

Members of the House of Assembly rejected the bill, with Manzini North MP Macford Sibandze saying the law targeted “citizens and the independent media”. Siphofaneni MP Mduduzi Simelane, a vocal dissenter on most issues debated in Parliament in 2020, was particularly harsh: “We can’t arm this brutal government with such a law. It will use it against the citizens. We have seen this happening before.”

The bill was subsequently withdrawn. It was yet another victory for progressive sections of the eSwatini Parliament.

Car clash

Then, in October, MPs went on to reject Minister of Finance Neal Rijkenberg’s Legal Notice 183 of 2020, which ruled that vehicles imported into the country shall not be older than seven years at the date of purchase. Many of the cars on eSwatini roads are imported from Japan. Some of these cars are as old as 15 years when they are bought. It is all many eSwatini residents can afford.

Not many people in the country are employed in the formal economy. Many scrape a living in the informal sector and in neighbouring South Africa. They do not have a credit profile. So, for cars, they go to the many Pakistani dealers in Matsapha and other towns. Prices range from R35 000 to a little over R100 000, depending on the make. And buyers can arrange to pay in instalments, over many months.

For days, members of the House of Assembly debated the notice and rejected the finance minister’s stipulated seven years, eventually settling for 12.

Related article:

Simelane spoke strongly against the notice, saying it goes against “public interest”. People in rural parts of the country depend on these cars to get to towns and health centres, he said. Government ambulances sometimes cannot attend to emergencies such as women in labour, for example, because there are often fuel shortages.

The ministry’s initial claim was that these cars are an environmental concern, but it later admitted that the ban was a measure towards improving the country’s earnings from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). A member state’s share of revenue drops when most of its imports are from outside SACU countries. Rijkenberg hoped that the ban on most Japanese car imports would help improve eSwatini’s profile in the customs union, leading to an increase in receipts.

In the end, it did not matter as MPs rejected the notice.

Progressive elements of the house would have scored even more victories had their resolution on the controversial Prevention of Organised Crime Act been successful. The act, passed in 2018 before the current MPs were elected to Parliament, was later used to target cannabis growers in the country. MPs opposed the manner of the act’s application in 2020 and sought to repeal it. However, their efforts proved futile as only a court of law can order the repealing of a law already approved by both houses of Parliament and assented to by the king.

No democracy

That 2020 was a particularly busy year for the eSwatini Parliament, especially the House of Assembly, may appear to be democracy in action to the outside observer. But human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko – jailed in 2014 for 15 months, after questioning the independence of the judiciary – warns against looking at recent events in Parliament as democracy in action.

“The mere fact that some bills have been withdrawn does not necessarily mean that that’s a victory for democracy, or even a victory within the context of democracy. And besides, we don’t know if they are withdrawn permanently. They might come back at some point, in a different form,” he said.

“I am not even sure if the ‘fights’ in Parliament are informed by an intention to advance democracy in Swaziland … That’s why I am not sure that can be said about this Parliament.”

Related article:

Mabuza, however, said he and some of his colleagues are exercising their rights by speaking up in Parliament. By opposing motions and bills openly and at this scale, they are “exercising democracy without fear. We now want to talk [about what] exactly the issues of the electorate [are], because we have been representing the people.”

When asked if he hopes to see the end of the current system, he said: “If the people of eSwatini want the change from Tinkhundla to democracy, then us representatives need to represent them. Because we are the voice of the people. So, whatever they want, we need to do it without fear or favour.”

The system is the problem

Maseko said the main problem in eSwatini is the system of governance, and that meaningful debates in the service of democracy should be directed at that. “But there is never a debate around the system of government. The elephant in the room is the system.

“Even if one accepts that there are one or two MPs who appear to be progressive, they have not challenged the root cause of the problem of the Swazi people, which is Tinkhundla as a form of government. That is where we have a problem in this country. All these other things don’t matter. There has been no direct challenge of the system by this Parliament. Of course, these people are elected through the very same problematic system.

“If perhaps the debates were saying these bills are intended to entrench Tinkhundla as a system of governance and therefore they can’t be allowed, perhaps one could say there is some hope. If that were the position. That is, if their argument was that the system is an impediment to achieving greater democracy for the whole of Swaziland.”

Related article:

Makhanya agreed with Maseko. “One can start by saying, at the moment, our opposition to the regime is an opposition to a system that goes beyond spontaneous individual actions here and there. It is about the system.

“So, a pronouncement by a member of Parliament, a progressive pronouncement, does not change the systemic repression of a regime,” said Makhanya.

“Small victories matter, definitely. But it is important that we don’t get jaundiced from small victories and start confusing a need for a solution for a bigger problem by elevating small victories, making them appear like they signify real victories.”

Makhanya reiterated Maseko’s point that these seemingly progressive moves would mean more if they were directed at the system of governance itself. He said this affects every aspect of the country’s running. “But our position has always been clear, my brother. In Swaziland, the king enjoys executive, judicial and legislative absolutism. It is for that reason, for example, that in November last year Judge Ticheme Dlamini of the high court said to litigants on a matter that was before him that these people must seek the intervention of the king to resolve the matter.

“This is a judicial question and here is a judicial officer of the high court, instead of adjudicating the matter based on what the law says, he is sending the matter to the king. And there is nowhere in the Constitution where it says legal matters must be resolved by paying respect to the king. What instrument is the king going to use to resolve legal matters?”

Makhanya said Parliament operates in a similar vein.

Still a site of struggle

Pudemo still views Parliament as important, despite its limitations. Makhanya said his organisation is willing to work with MPs who want to fight for the people.

“Even where we take a principled decision as a party to say we are not going to participate in Tinkhundla elections, for instance, it does not mean that we are not going to regard Parliament as an important site of struggle.

“But we simply say … if we were to tell our people that if you elect us into this platform, this platform will automatically transform into a representative platform, we would be lying.

“But if we do have people who are there, who are willing to fight for the people, they will always find an ally in Pudemo. And that has always been our posture.”