Eradicating pit toilets is but a first step

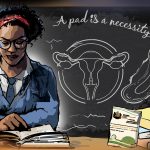

These dangerous and insanitary latrines at schools should be replaced by clean and safe bathrooms that also cater to the needs of girls who’ve reached puberty.

Author:

22 September 2021

It’s been seven years since Michael Komape, 5, fell into a pit toilet and drowned at Mahlodumela Lower Primary School in Chebeng village near Polokwane, Limpopo. The tragic death of the grade R pupil prompted the non-governmental organisation Section 27 to institute legal proceedings against the Limpopo Department of Education and the Department of Basic Education to provide safe and proper sanitation facilities at schools in the province.

In April 2018, the high court in Polokwane instructed the two departments to supply and install at each rural school with pit toilets “a sufficient number of toilets for each school for the use of children which are easily accessible, secure and safe and which provide privacy and promote health and hygiene based on an assessment of the most suitable safe and hygienic sanitation technology”. They also had to conduct a comprehensive audit of the sanitation needs at schools in the province and present a comprehensive plan for the installation of new toilets.

The departments submitted the list of schools with pit toilets and their plan to eradicate these latrines in August 2018 and provided a progress report in May 2020. However, believing the plan to be “unconstitutional and unreasonable”, Section 27 returned to the high court in August this year.

Related article:

On 17 September, delivering its ruling, the high court called for the eradication of pit toilets across South Africa and not just in Limpopo. Judge Gerrit Muller said that “the replacement of pit toilets is a national emergency and must be treated accordingly”, and expressed his disappointment at the lack of urgency to dealing with the issue.

“The proposed 14-year period [to eradicate pit toilets] is unduly long. The rights of the children who are attending school presently are being ignored. They are in constant danger when attending school and when they are compelled to utilise these dangerous toilets, some of which also do not afford adequate privacy. The dignity of many learners are seriously impaired when they have to use these facilities. It cannot be countenanced. Another unfortunate and tragic death of a child at school due to dangerous pit toilets will be a catastrophe that should be avoided at all costs.”

Julia Chaskalson, Section 27’s communications officer, said: “When we returned to court on 6 August to continue the fight for dignified, lawful and safe school sanitation infrastructure, we argued that [the departments’] plans for the eradication of pit toilets by 2030 are unreasonable, unconstitutional and inadequate.

“Their plans do not allocate sufficient resources to deal with the problem of hundreds of schools in Limpopo solely relying on pit toilets for their sanitation needs, and neither do the plans explain how financial mismanagement and underspending – which the department has a long track record of – can be reversed.”

Imminent danger remains

According to Chaskalson, the data of schools with pit toilets in Limpopo are contradictory and incoherent, making it difficult to track progress made to deliver sanitation infrastructure.

“The imminent danger posed by the presence of pit toilets … is not addressed by the so-called plan of the department, which claims it can only resolve the issue between 2026 and 2030.

“With each day that education authorities delay the delivery of safe and decent sanitation in schools, learners remain at risk of being harmed and dying in a pit toilet. For as long as pit toilets continue to exist at schools across the country, learners’ rights to dignity, equality, basic education and a safe environment are jeopardised,” she said.

Nokuzola Ndwandwe, an activist for menstrual health and the founding director and chief executive of the grassroots collective Team Free Sanitary Pads, says owing to a lack of clean and safe toilets, young girls face possible exposure to infections as well as sexual assault.

Related article:

“When girls don’t have access to safe toilets to manage their periods, it exacerbates the stigma and the shame as well as contributes to societal mentalities that a period is unclean. And the government not acting with urgency to provide flushing toilets is merely making a clear statement from its actions that these taboos should not be deconstructed. As a result, girls become fearful of their bodies, and this impacts their performance at school as menstrual health has an impact on one’s mental health,” she said.

Tidimalo Chuene, spokesperson for the Limpopo education department, did not respond to questions sent to her. Instead, she shared a media statement issued by the Department of Basic Education on 5 August 2021 and said it “stands in response to questions around the pit latrines court case at the moment”.

According to the statement, the Sanitation Appropriate for Education (SAFE) initiative was launched in August 2018 to accelerate the provision of sanitation facilities in the identified schools. “The SAFE initiative is a flagship programme and I have resolved that I will carry out the monitoring function until the last school has a proper toilet,” Mathanzima Mweli, the director general of the department, said in the statement. “The monitoring has pushed our performance up and we are sure to hit our target even before the end of the current financial year.”

Sanitation crisis

Candice Chirwa, a menstruation activist and author, agrees with Ndwandwe that pupils in South Africa face a sanitation crisis. She believes that girls require more female-friendly sanitation facilities for when they menstruate.

Chirwa says proper menstrual health management requires access to menstrual products and clean and accessible infrastructure that allows girls to manage their periods with dignity. The sanitation infrastructural requirements include bins, basins with clean water and toilet paper.

“Women and girls are often ignored in the planning and design of public toilets and clean sanitation. Access to water and soap for cleaning hands or the body or washing period products is required for young menstruators to manage their periods,” said Chirwa.

“Sanitation is a human right, yet women and girls often cannot go to the toilet when or where they need it. This impacts their freedom, their health and their ability to participate in public life. In ensuring access to adequate public sanitation, it would therefore address an overall global sanitation crisis.”

Related article:

Chirwa warns that people underestimate the impact that poor sanitation facilities have on children. “A lack of access to proper sanitation poses a huge barrier to education. The availability of clean, safe and accessible toilets can encourage children, especially girls, to go to school and remain at school.

“Reaching puberty is often a scary time for young girls, and oftentimes young girls will have to frequent the restroom to attend to their private needs. If the school does not have adequate facilities, then this could be a determining factor in girls remaining at home, especially when they are menstruating, and thus impacting their school attendance.”

Ndwandwe agrees that female-friendly toilets are important. “Such toilets could have the needed menstrual health education and awareness [materials] on the bathroom walls to help deconstruct the narratives and end period stigmas.

“The toilets would have free period product dispensers, which would mean no more stress of period poverty for girls. [This would] help alleviate mental health concerns such as possible depression from premenstrual syndrome, which tends to be exacerbated by period poverty,” says Ndwandwe.