Drawing everyday heroes out of the archive

A new comic book anthology inspired by the Supreme Court of Appeal archive brings to life an era of popular resistance during the early 20th century.

Author:

26 November 2021

One does not simply walk into a court archive. Historical researchers everywhere know the psychological perils of such places: the brutal, strip-lit loneliness, the ghosts of old injustices, the endless, taunting promise of documentary gold waiting in the next folder or the next trolley.

But the Mexico City-based South African historian Richard Conyngham does not lack endurance, whether mental or physical. He once cycled all the way from Mexico City to Tierra del Fuego, and he is set to climb Mount Aconcagua next month. Conyngham emerged unscathed from a long adventure in the Supreme Court of Appeals basement archive in Bloemfontein – with a trove of courtroom drama.

The result is All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa 1910-1948 (Jacana, 2022), a groundbreaking graphic history of pivotal struggles fought by workers, traders, washerwomen and farmers against the pre-apartheid state.

Related article:

To reanimate these tales of defiance, Conyngham head-hunted a team of stellar artists to draw the stories – including the Trantraal Brothers, Saaid Rahbeeni, Liz Clarke, Dada Khanyisa, Tumi Mamabolo and Mark Modimola. “It was a huge challenge to recruit and sustain those artists. I was very picky, and wanted to find artists that had some kind of bond with the story, not necessarily a direct one.”

The idea was to use the visual punch of the comics medium to hook the attention of young readers and dramatise a neglected era of South African struggle history. “The court records revealed an incredibly colourful and explosive period,” says Conyngham. “But you don’t get that sense from school or university history syllabuses.”

Of compassion and comics

As Edwin Cameron notes in his foreword to All Rise, some of the stories offer a reminder that “the law, when used properly, even in times of great injustice, can produce outcomes that are just”.

That said, Conyngham says he did not sense many flickerings of judicial compassion in the records. “It was respect for the law that the judges had, rather than an empathy for the people involved,” he says.

“Often they come across as very racist or sexist, even when they rule against the state. There was always room to move, and certain judges were so by-the-book in the reading of the law that they would sometimes rule in ways you wouldn’t expect. I think Edwin really experienced that as a lawyer during the apartheid years, that the judge’s respect for the law could be taken advantage of if you were really good in the courtroom.”

In her foreword, historian at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research Hlonipha Mokoena notes the thread of migration that binds the stories – nearly all the litigants or defendants, be they Black, white or Indian, are migrants of some sort, fighting for the rights afforded to (some) citizens. That struggle is still with us, and these stories, she writes, “are an affirmation of the reasons why our Constitution is not just a legal nicety but a moral imperative”.

But some of the historians Conyngham consulted were not excited by the medium, he says. “There is a bit of a stigma around the comics genre that lingers in academia – partly because some feel threatened by it. Along the way, I got hold of many of the authorities on the different areas I was researching. Some were very receptive and others were not at all, as though they didn’t – or didn’t want to – take the medium seriously.”

Scripting stories

All Rise began with a project started by HIV and Aids activist Zackie Achmat, who enlisted Conyngham as a researcher in 2015. “It was Zackie’s idea to go to the Supreme Court of Appeals archive,” says Conyngham, “because through his legal activism, he had discovered some of these obscure judgments from the early 20th century, such as that of Rex vs Detody (1926). So we went to Bloemfontein and did a lot of photocopying. We left with the records of about 12 to 15 cases, some of them thousands of pages long.”

In due course, Conyngham had the idea of writing a graphic anthology, as opposed to the conventional history book that they had initially planned. With Achmat’s blessing, he started out by approaching his friend André Trantraal, a luminary of the South African comics scene, with whom he had already collaborated on a graphic companion to the O’Regan-Pikoli commission into Khayelitsha policing.

Conyngham wrote the scripts himself, with some tough guidance from the artists when it came to cutting extraneous detail. Graphic non-fiction can communicate historical complexity, sometimes more effectively than documentary film can, because of the radical freedom of a drawn line. For example, the books made by Joe Sacco, Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel do things with true stories that no prose book could achieve.

But the form does demand narrative economy if it is to be readable – something Conyngham achieved by moving much of the historical background into superbly designed appendices at the end of each story, complete with contemporary photos of the settings, the protagonists and their handwritten letters.

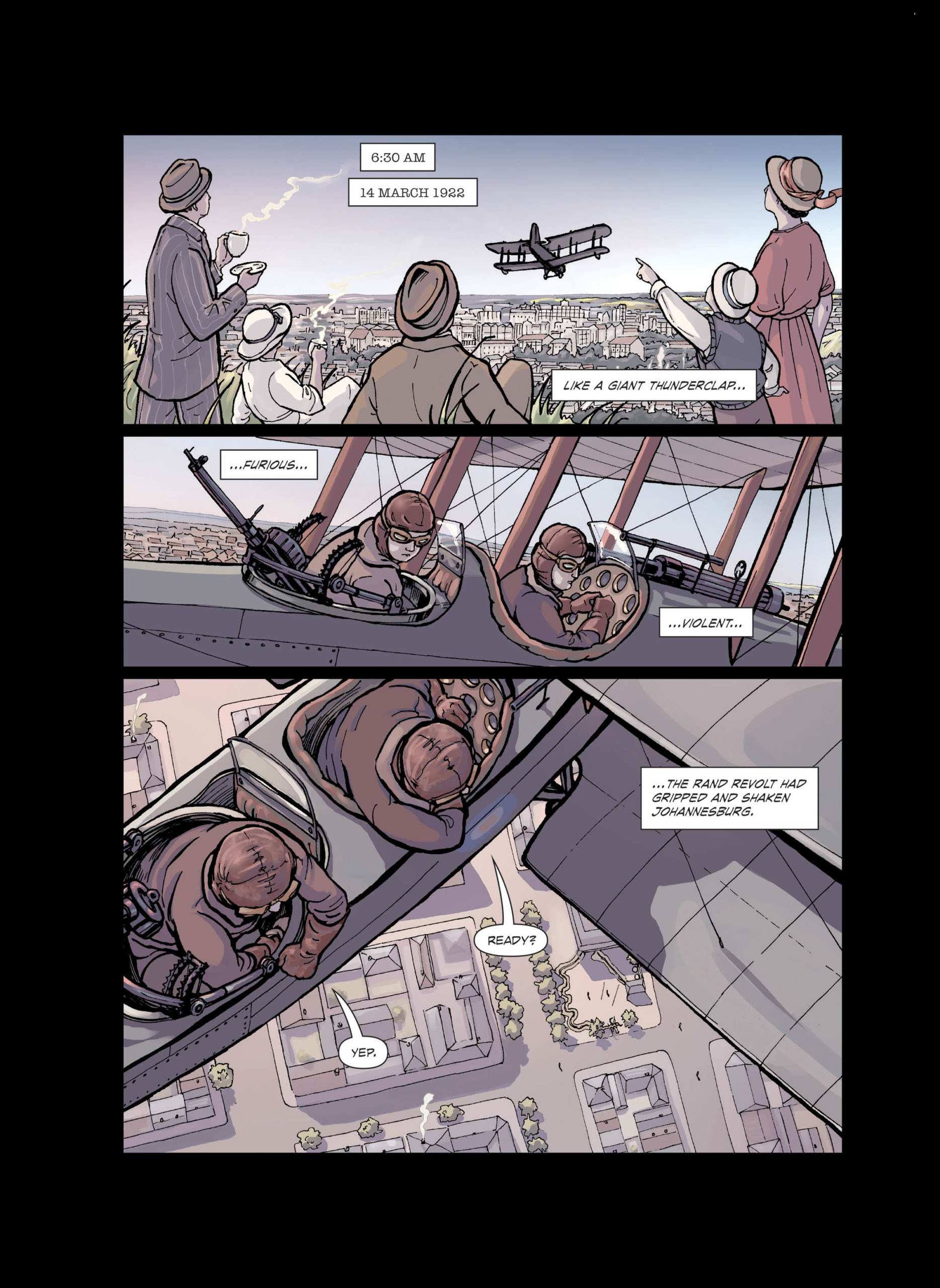

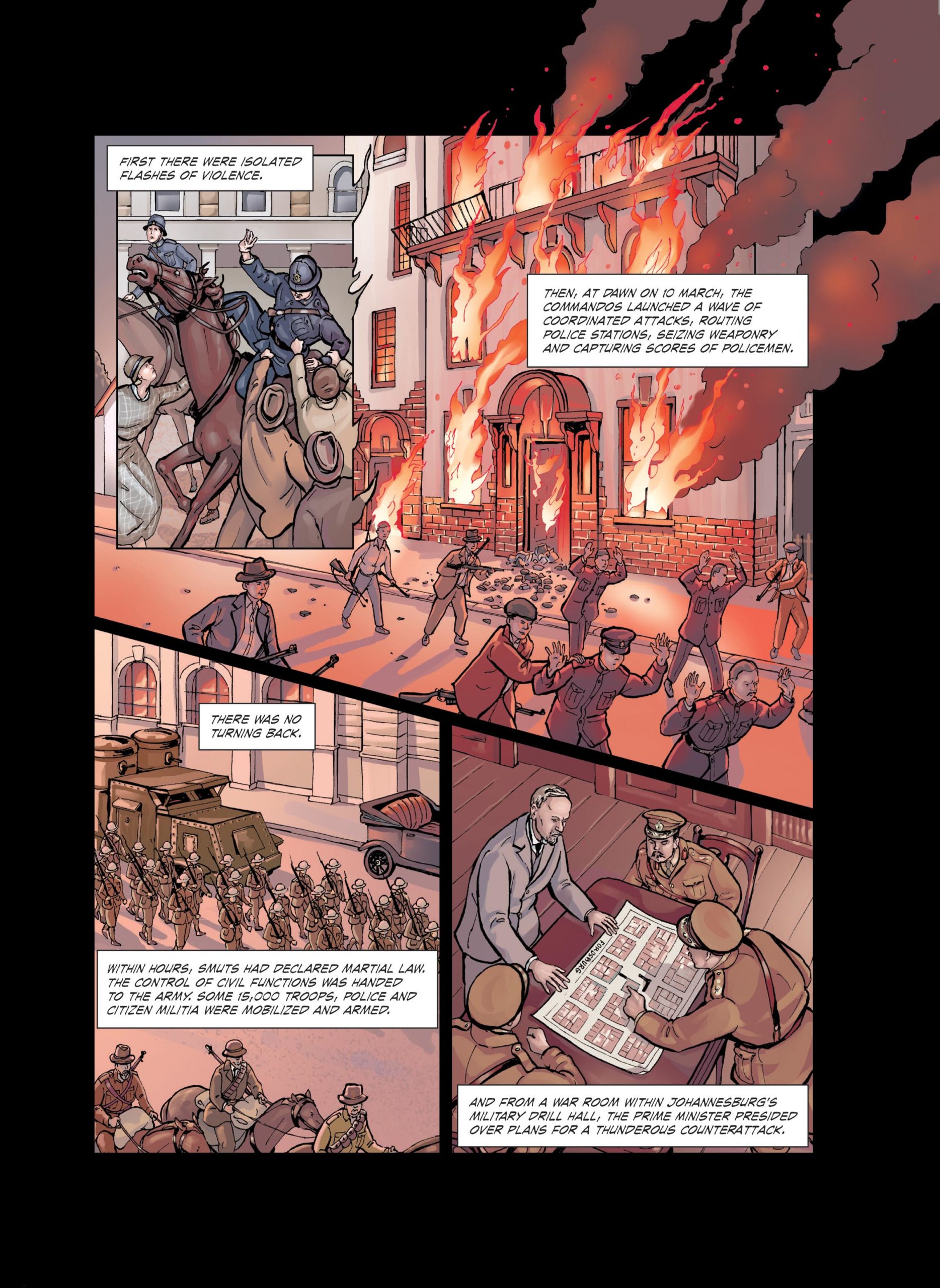

The National Archive even provided actual clippings of the hair of the 1922 Rand Revolt striker Taffy Long, who was convicted for executing a spy. The samples were an exhibit for the Crown, who argued he had deliberately altered his hair colour using permanganate of potash. The trial of Long, who was executed at Pretoria Central Prison, is brought to dark, cinematic life by Clarke in Come Gallows Grim.

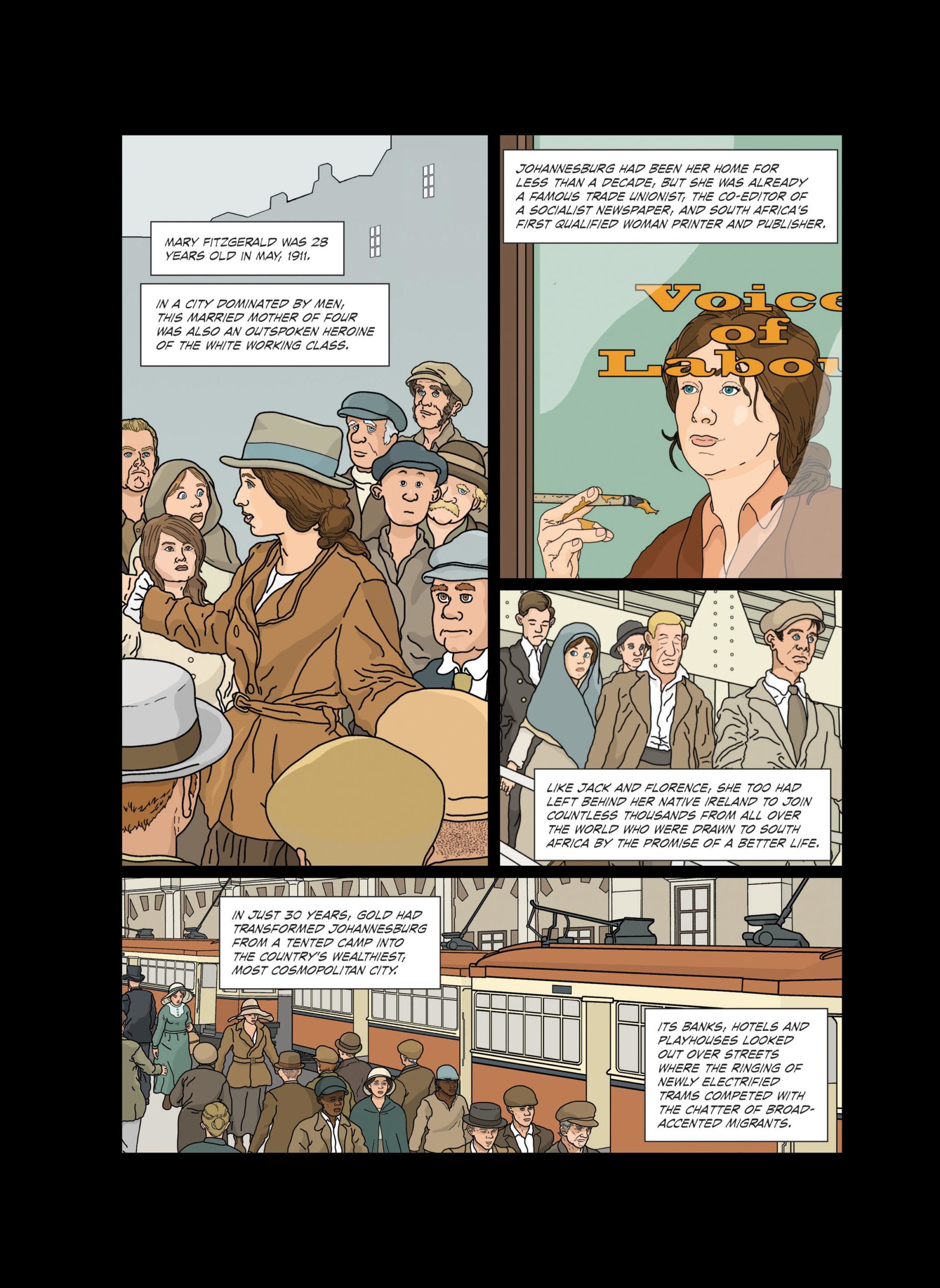

In the Shadow of a High Stone Wall sees the Trantraal brothers, Nathan and André, tackling the story of Jack Whittaker, a Johannesburg tram worker who downed tools in a 1911 strike. At the heart of the action we encounter Mary Fitzgerald, the pick-handle-wielding firebrand of Joburg’s early class wars. Whittaker was framed for the possession of explosives. His eventual acquittal was a victory, but not as significant a precedent as his later victorious claim for damages from the state for inhumane confinement while awaiting trial.

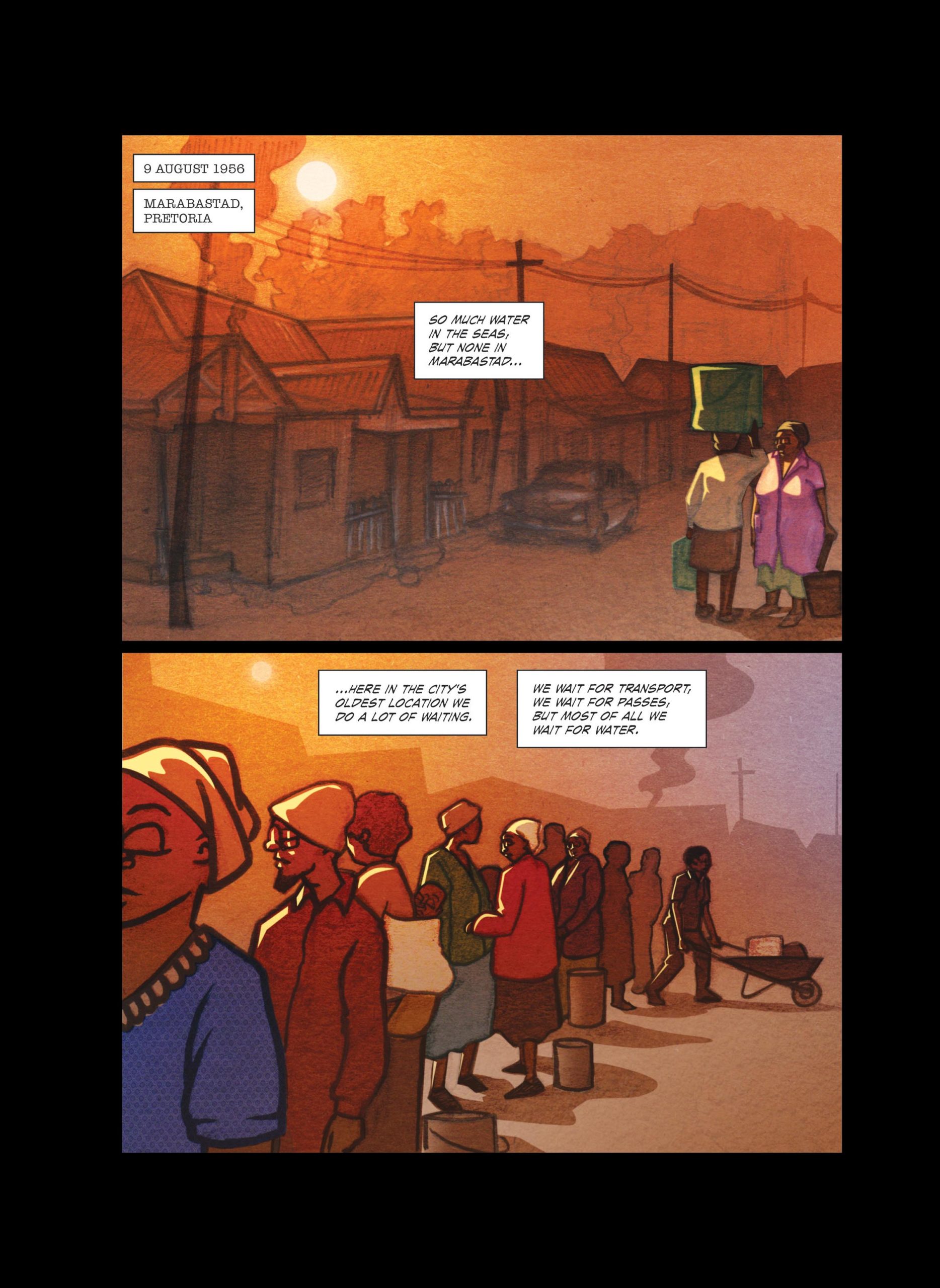

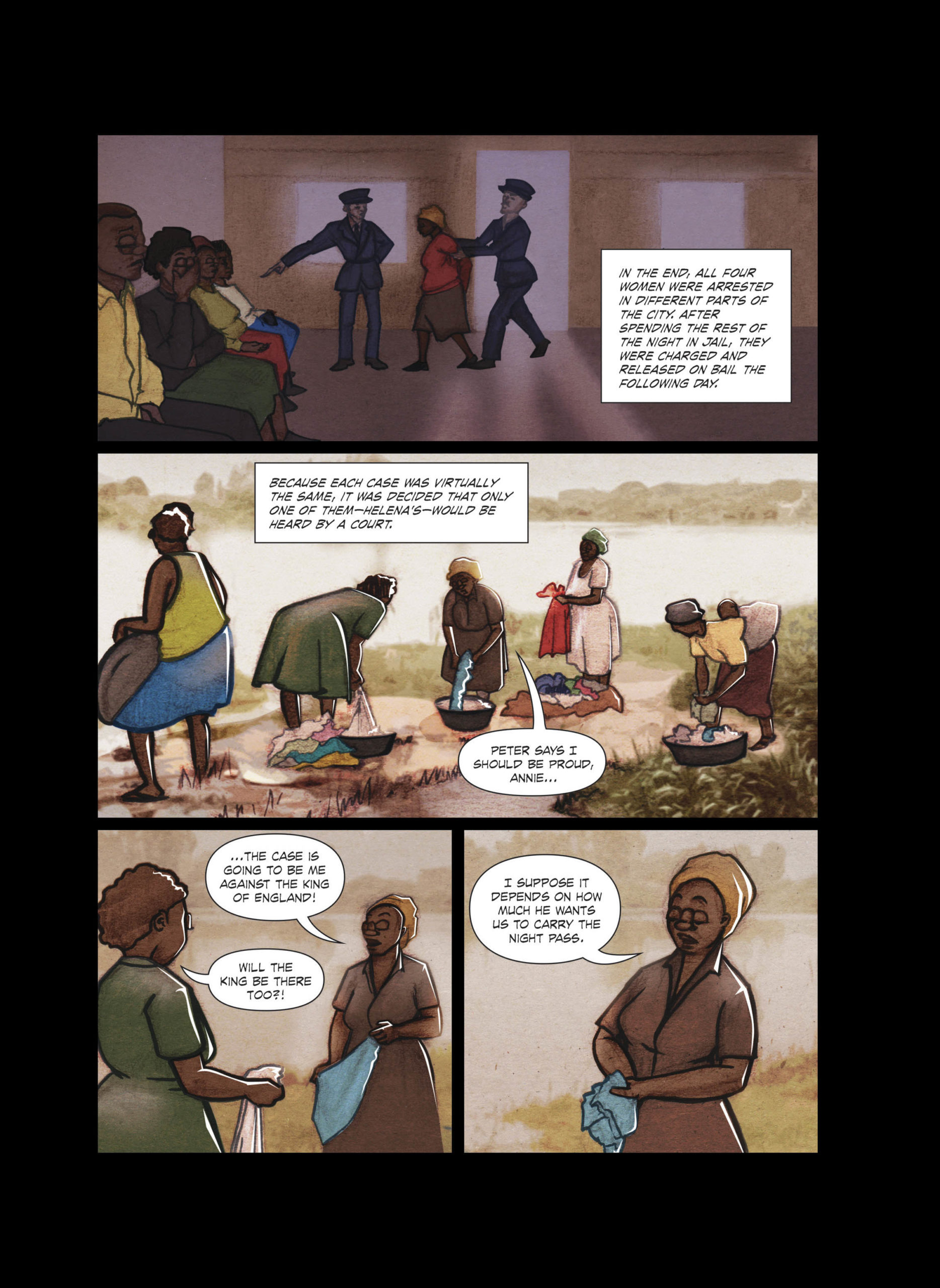

Khanyisa’s radiant artwork illustrates The Widow of Marabastad – an account of a long battle against the imposition of night passes for Black women in the Transvaal. It was led by a Pretoria washerwoman, Helena Detody in 1926. With the help of the Transvaal Native Congress, she took her fight for the right to move freely through the city all the way to the Supreme Court in Bloemfontein. Detody’s triumph secured free movement for Black women in the Transvaal for 20 years.

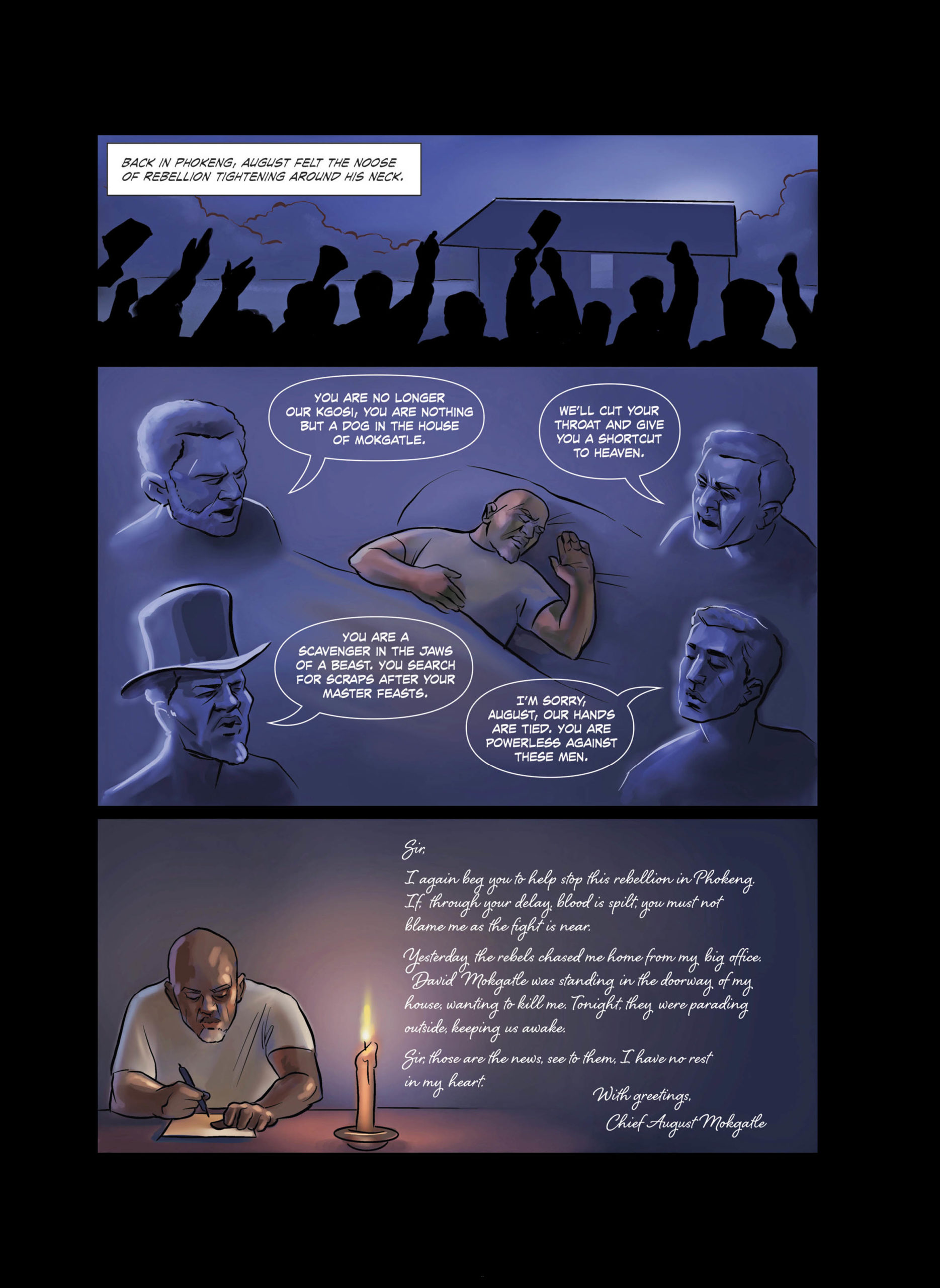

Mamabolo drew A House Divided, about the 1922 showdown between the Bafokeng chief August Mokgatle and his lekgotla, or tribal council. Mokgatle’s councillors had rejected his weak and erratic leadership, partly inspired by the democratic ideas of a Black Jamaican reverend who had settled in Phokeng, Kenneth Spooner. Despite the impassioned courtroom testimony of Sol Plaatje in defence of the rebels and their ideals, the Department of Native Affairs won the case and banished them – paving the way for Bantustan puppet governments and the erasure of precolonial forms of tribal democracy.

In Until the Ship Sails, Rahbeeni illustrates the story of Mahomed Chotabhai, a 15-year-old Indian boy who was barred from joining his merchant father in Johannesburg as a result of the Jan Smuts government’s crackdown on “free” Indian workers. At the time, the registration certificates introduced for Indian workers in the Transvaal – an effort to criminalise new migrants – sparked a defiance campaign of certificate burning, and the Chotabhai case was taken on by Mohandas Gandhi.

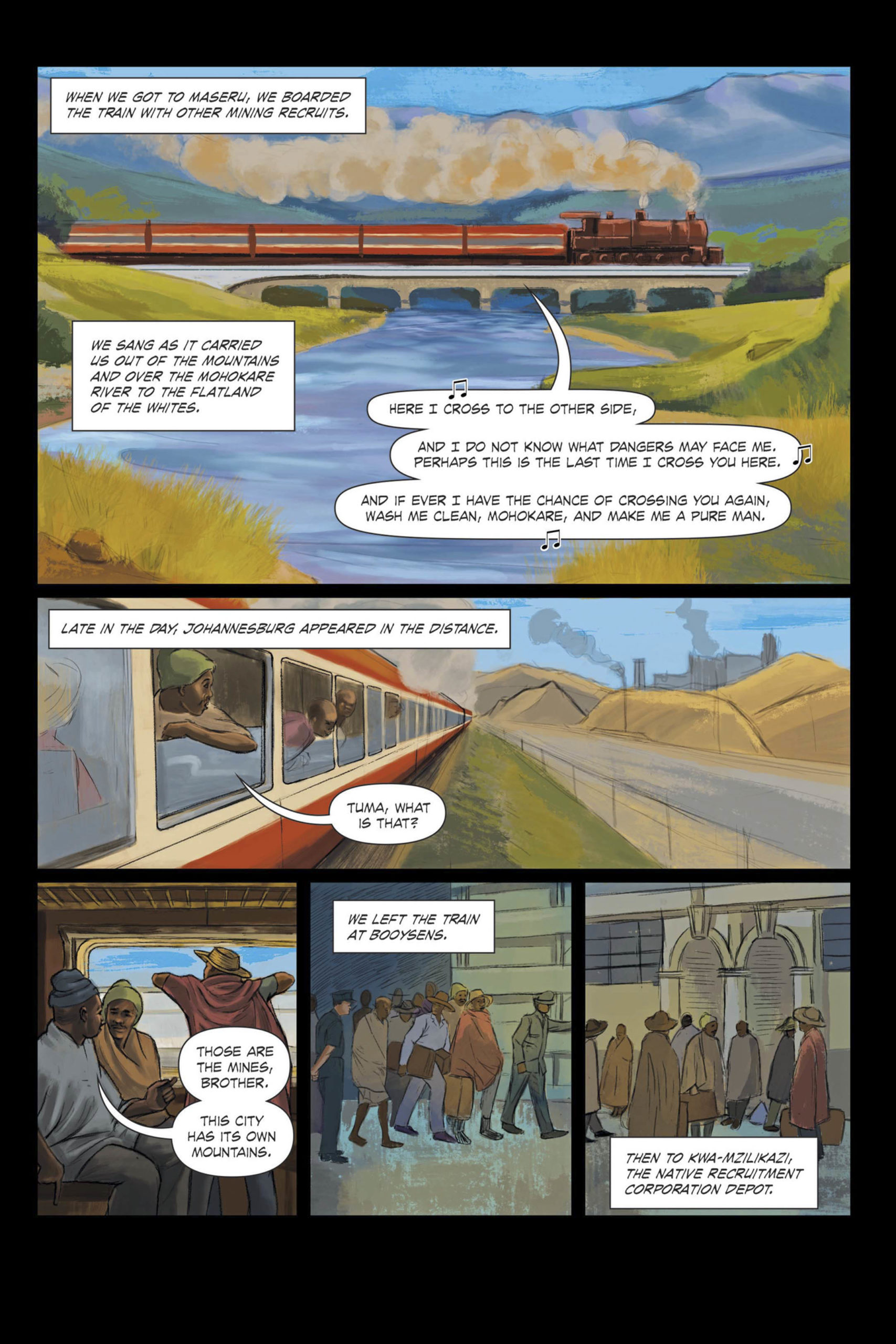

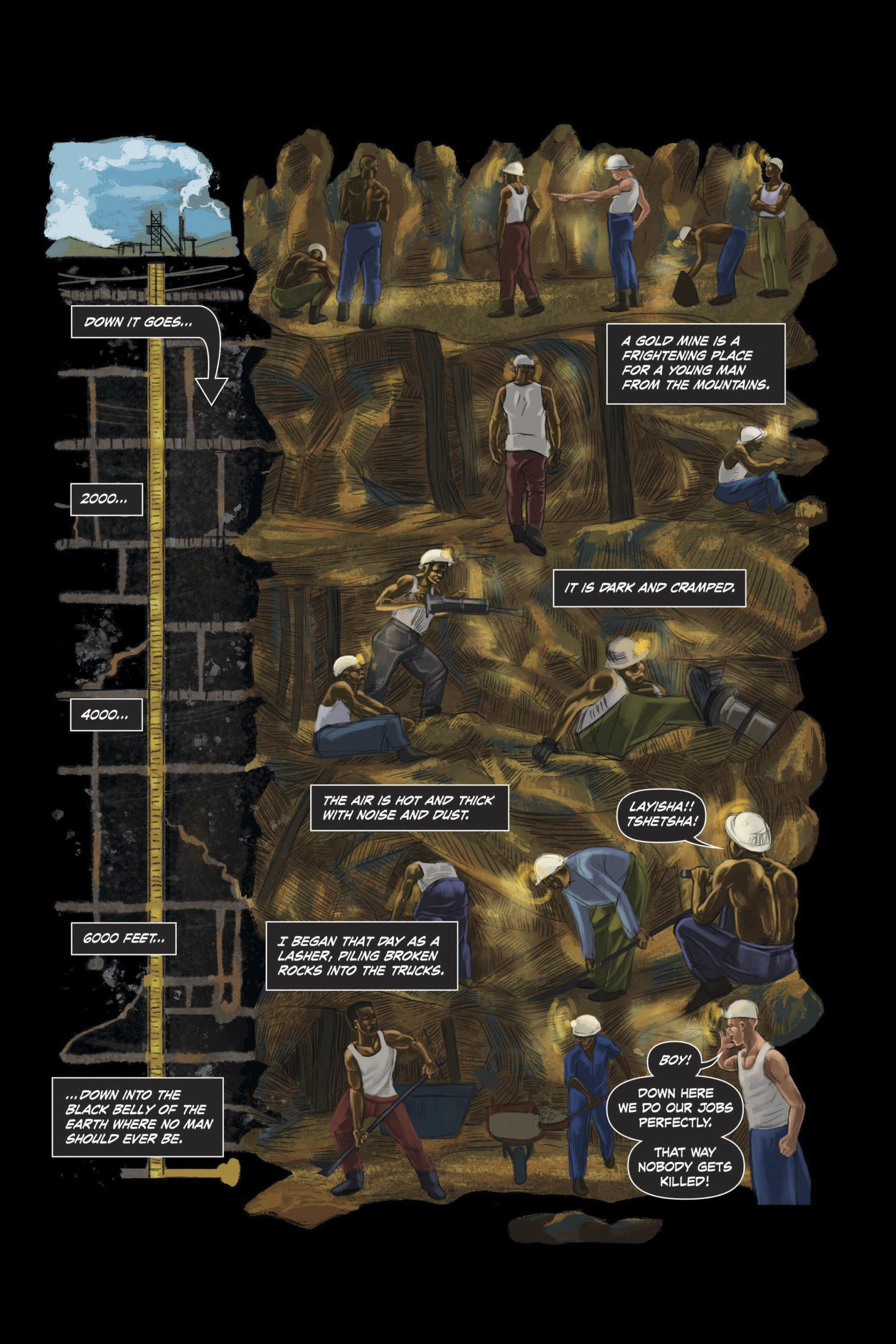

And in Here I Cross to the Other Side, Conyngham and Modimola expertly reconstruct the world of the 1946 miners’ strike on the Reef, which was violently suppressed along with the African Mine Workers Union, which organised it. It is less a factual narrative than a skilful imaginative reconstruction of a young Basotho recruit’s first journey to the Reef and the frontlines of resistance. While the 1946 strike failed to bring fair wages and living conditions, its legacy shaped the rebirth of organised labour decades later.

All Rise is a moving tribute to the power of the ostensibly powerless, and a quiet corrective to the apathy and despair that haunts South Africa right now. As Conyngham says: “It’s possible for everyday people to use the law courageously in ways that can actually cause lasting, systemic change. Although we tend to wait for a truly extraordinary person to do it for us, the stories in this book show that there are also ways to do it for ourselves.”