Don’t touch me on my stadium. You hear me?

Loud voices insist that politics has no place in sport and athletes should stay out of it. But there seems to be plenty of space for them to support causes other than the fight against racism.

Author:

12 October 2021

Time ticks towards a match in a stadium that shimmers with promise. These are the snap, crackle and pop moments when hope knows no bounds. Anything could happen in the coming seconds, minutes, hours, days.

Where you have come from to be here doesn’t matter. Neither does your race, gender, sexual orientation, size or age, nor to which religion, culture or world view you belong. What does matter is that you are here now, united in the cause of supporting your chosen player or team. Can there be a more pristine democratic space in any society, emptied of agendas and utterly apolitical?

Except that politics is everywhere, and not least in sport in South Africa. Can you spare the money to buy a ticket? Are you among the masses in the stands, or have you set yourself apart in the splendid isolation of a private suite? Do you belong to the credentialled classes in that bubble of contending egos and ideologies, the press box? Or are you working in a low-paid job – behind a broom, a bar or a food counter?

Related article:

How did you get here? In a bus, a minibus taxi, an Uber vehicle, your own car? Do you live close enough to walk or ride a bicycle? Are you in your comfort zone of town, or have you had to leave the township for the suburbs, or the suburbs for the city centre?

Each of these questions has a political dimension. Your presence at the stadium is not coincidental. You are here because of decisions, large and small, taken by you and others. Some were made hundreds of years ago by people who held the power to shape your destiny.

Although these truths should discomfort us, they are unlikely to anger us. But, should the players we have come to watch dare to state their position on issues that go beyond the narrowly defined boundaries of sport, outrage there will be. Well, certain issues, that is.

Selective outrage

When the Proteas turn out in pink to raise funds for and promote researching a cure for breast cancer, no one objects. Ditto when they take a stand against rhino poaching, or when they give all the credit for their success to their idea of a god. But the gods help them should they decide to oppose racism, the most murderous and debilitating chronic disease of all time, because suddenly the objections drown out everything else.

“I’m thinking of Lungi Ngidi wanting to take up the Black Lives Matter cause and getting a lot of flack from white former players,” said Wahbie Long, a clinical psychologist, academic and the author of Nation on the Couch: Inside South Africa’s Mind. “Maybe the controlling interests in a sport like cricket in South Africa are not politically progressive. So they have a problem when a sportsman like Lungi wants to do something different.”

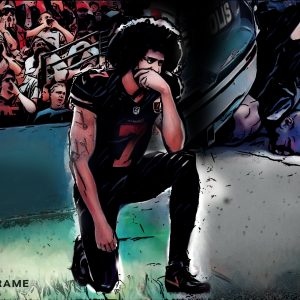

Ngidi is not alone. From Muhammad Ali and Colin Kaepernick to Naomi Osaka, players who make plain their politics have been vilified by a public that wants them to turn up, play and go home. It seems players aren’t human; they’re simulations in a video game and must go back into their boxes afterwards.

Related article:

LeBron James and Kevin Durant felt the sting of this view in February 2018 after they released a video criticising Donald Trump, then the United States president. Trump, James said, didn’t “give a fuck about the people”.

Conservative television host Laura Ingraham took offence on Fox News: “Must they run their mouths like that? Unfortunately, a lot of kids – and some adults – take these ignorant comments seriously. Look, there might be a cautionary lesson in LeBron for kids: this is what happens when you attempt to leave high school a year early to join the NBA [National Basketball Association].

“And it’s always unwise to seek political advice from someone who gets paid $100 million a year to bounce a ball. Oh, and LeBron and Kevin: you’re great players but no one voted for you. Millions elected Trump to be their coach. So keep the political commentary to yourself or, as someone once said, shut up and dribble.”

Daring to define yourself

Invariably, Black players suffer more for holding political opinions. Is this unavoidable in a world of white supremacism, or does it reflect that, too often, their white teammates don’t stand with them? When they do, as with England’s football team taking the knee, the shock and horror in the stands and beyond is palpable.

In 1967, when Ali refused to be drafted for US military service because of his opposition to his country’s involvement in the Vietnam War, he was fined, sentenced to prison (though he remained free on appeal) and stripped of his world title. He also wasn’t spared in the press.

Red Smith, a luminary of the New York sport press pack, wrote: “Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius [Clay, Ali’s birth name] makes as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war.”

Related article:

The feeling was mutual across the country, with Jim Murray writing in the Los Angeles Times: “Cassius Marcellus Clay, one of the greatest heroes in the history of his people, has decided to secede from the Union. He will not disgrace himself by wearing the uniform of the army of the United States … From the safety of 103 years, he waves his fist at dead slave owners. Down to his last four Cadillacs, the thud of communist jackboots holds no dread for him. He is in this country but not of it.”

A few years earlier, after Ali’s conversion to Islam and shedding of his birth name in 1964, leading New York columnist Jimmy Cannon had written: “The fight racket since its rotten beginnings has been the red light district of sports. But this is the first time it has been turned into an instrument of mass hate … Clay is using it as a weapon of wickedness. I pity Clay and abhor what he represents. In the years of hunger during the depression, the communists used famous people the way the Black Muslims are exploiting Clay. This is a sect that deforms the beautiful purpose of religion.”

The use of Clay instead of Ali by all of them was no oversight. It took years for the New York Times to require its reporters to call Ali by his chosen name – to accept his dictum, which he had unfurled after beating Sonny Liston: “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want.”

Rocking the establishment

Like most of their editors and readers, Smith, Murray and Cannon were white. Almost six decades later, it is still the colour of power and authority in the many societies in which whites think it is their right to define Blackness. It has fallen largely to Blacks to expose and oppose that reality.

“Causes like Black Lives Matter are going to resonate with players who come from underprivileged backgrounds,” Long said. “They are going to want to be active on those kinds of platforms, and then they’re going to run into problems like Lungi has. The establishment, in certain instances, doesn’t look kindly on political activity by sportspeople.”

Even Black players who don’t take political stances are targets for racist abuse. As we learnt from social media during the Euro 2020 finals in July, having a penalty saved while Black is a crime against football. But should a white player balk at explaining his decision not to take the knee, or raise a fist, or stand to attention in support of the fight for social justice, the fans come down on the reporters who have the audacity to ask him why. Will the real Quinton de Kock please stand up?

Related article:

And De Kock is not alone. Bafana Bafana have played more than 10 matches since the Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd on 25 May 2020. Not once have they taken a knee. Why?

“If I think about how racially divided South African society is, and the fact that South African football is a predominantly Black sport, then it may well be that our Black footballers are moving mainly in Black circles,” Long said. “So all that stuff that kicks in when social comparisons are activated isn’t relevant.

“For someone like Ngidi, who is a Black man from an underprivileged background moving in white circles, race and privilege are more salient. All those contrasts are in your face. It’s hard to not feel some degree of resonance with a cause like Black Lives Matter.

“There’s that great passage from Marx where, to paraphrase, his point is that the problem with inequality is not that you live in a shack but that the shack is in the shadow of a palace. That’s what fuels the tinderbox of emotion.”

The admirable vs the deplorable

Some don’t need injustice spelled out so clearly. Graham Mourie refused to captain the All Blacks against apartheid’s Springboks in 1981. Thousands of New Zealanders protested against the tour and were met with state violence.

Brazilian midfielder Sócrates co-founded and led his Corinthians team’s democracy movement, which would inspire the nation to stand up against the military dictatorship. The players insisted on filtering everything they did through a political prism. In 1983, after beating rivals Sao Paulo, they carried a banner on the field that read “Ganhar ou perder, mas sempre com democracia (Win or lose, but always with democracy)”.

Sadly, for every Mourie, woke Kiwi, Sócrates or Ngidi, there’s a Roland Schoeman – once an Olympic swimmer, now the author of bumptious letters to President Cyril Ramaphosa offering his services as minister of sport. “For far too long politics and ideology have polluted sports to the point that many federations are in dire straits,” Schoeman wrote on 3 August.

Related article:

“We need a minister of sport who is more interested in getting our young men and women to the point of success on major international platforms than the politics of federations and sports clubs. Surely we want to win as a nation?”

And surely we’re willing to sacrifice anything for victory: integrity, conscience, the responsibility of not only being in a society but also of it.

That’s what’s coming soon to a stadium near you. Anything could happen, but not if it’s political.