Directory of police crimes tells a brutal tale

With almost 50 000 cases against officers, ranging from rape to death in custody, a new database of police crimes shows apartheid’s authoritarian tactics still pervade the institution.

Author:

25 November 2021

In October, Viewfinder, a journalism project that focuses on police accountability, published a searchable database of charges made against officers in the South African Police Service. Listing almost 50 000 individual cases between 2012 and 2020, the database is a litany of torture, abuse and shootings, and should be of serious concern to anyone worried about the fate of South African democracy.

It is based on reports made by the public against officers. The Independent Police Investigative Directorate (Ipid), a body tasked with ensuring police accountability, is supposed to probe these reports, which come from every police station in every province.

They detail a systemic pattern of officers implicated in violence, including assault of alleged suspects and random members of the public; the unlawful discharge of firearms; suspicious deaths in custody; the widespread use of apartheid-era torture methods; rape and sexual assault of people in custody and in their homes; and soliciting bribes.

Related article:

Beyond systematic violence and venality, the reports highlight an institutional culture of sadism and intimidation. Officers are accused of pepper spraying pregnant women and of shooting teenagers for talking back. Innocent people have been apprehended as armed robbery suspects and subjected to prolonged torture before being released after officers realised they had the wrong person.

On paper, postapartheid South Africa has existing checks and balances to ensure serious allegations against the police are investigated and that officers guilty of violence and delinquency are punished and fired.

The real story

The reality, as Viewfinder’s research has shown, is that bureaucratic inertia has allowed the flagrant abuse of the law to go unchallenged. Ipid is under-resourced. It has a huge backlog of investigations. It is also guilty of “‘completing’ poorly investigated cases to inflate performance statistics, while obstructing justice for victims of police brutality”. The database also shows a persistent trend of officers assaulting and intimidating people who report misbehaviour, which means that these Ipid charges could represent only a section of a vast number of unreported cases.

Officers implicated in serious criminality are often protected by what in other countries is called “the blue wall of silence”, in which police close ranks around delinquents in uniform. In South Africa, station commanders sometimes delay suspending or disciplining officers, saying they are waiting for the conclusion of Ipid cases. This has resulted in officers accused of serial violence against the public keeping their jobs.

Related article:

The government pays the legal costs from any criminal charges, meaning that police officers have no financial incentive to avoid abuse. It seems ironic that for an organisation whose members attack unarmed people for apparent disrespect, there is little actual regard for internal discipline and command.

Internal police surveys uncovered by Viewfinder reveal that a disturbingly high number of officers see no ethical or legal issues with soliciting bribes or resorting to violence. This widespread institutional malaise also means that officers who are committed to public service may find themselves marginalised and attacked when they attempt to whistleblow on illegal activity.

Police culture

These allegations against police are worrying. Members of the police service are not just public servants but armed representatives of the state. They are given substantial powers to both arrest and use force. Having a widespread culture of violence and criminality within the police is a serious threat to democracy. As the philosopher Cornel West argues, “The basic aim of a democratic regime is to curb the use of arbitrary powers – especially of government and economic institutions – against its citizens.”

Abusive and corrupt policing is effectively a form of everyday despotism, which uses terror and intimidation to prevent civil and individual freedoms. The refusal of commanders to discipline habitually delinquent officers makes a mockery of the basic principle of representative governance. And behind every bribe-seeking cop at a roadblock stands a host of kleptocratic officials and politicians who brazenly use the state for personal enrichment.

Related article:

These anti-democratic tendencies extend beyond the behaviour of individuals and stations, and into systematic state repression. In the last decade alone, both national and municipal police have killed protesters, including Andries Tatane in 2011 and the Marikana miners in 2012. They have also participated in sustained hostility towards grassroots movements such as Abahlali baseMjondolo.

Repression does not only entail brute force but also means preventing investigations, such as when officers choose to not pursue charges against politically connected elites.

Authoritarian drift

From the first private militias used by the Dutch East India Company to make a beachhead for the dispossession of indigenous people in the 17th century to the racist police state of apartheid, policing in South Africa has been historically defined by social control achieved with force and repression.

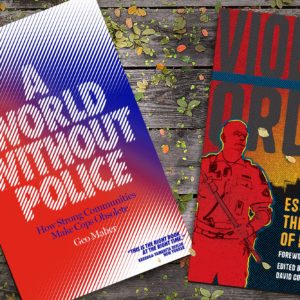

As Paul Erasmus’s shocking Confessions of a Stratcom Hitman underscores, apartheid police were not just agents of crimes against humanity, but also were involved in personal enrichment schemes and cultivated links to organised crime networks. Under apartheid, many in the police became criminals. Officers from all racial and ethnic backgrounds were hired for their violence and sadism, leading to an institution riddled with petty tyrants and outright psychopaths.

The postapartheid government inherited a police force that was effectively a domestic army of occupation. Reforming such an authoritarian institution was never an easy task, especially given the racial and class biases within policing training and practice. But for the past three decades, the ANC-led government has displayed a sustained lack of imagination in holding abusive officers to account.

Criminologist Ziyanda Stuurman’s book Can We Be Safe? – The future of policing in South Africa (NB, 2021) goes into this in detail, showing that the apartheid police was never extensively overhauled. Politicians such as Nelson Mandela promised there would be “no witch hunt”. Among the practical effects of this was that apartheid practices like torture were handed down to officers who joined after 1994.

Related article:

The government did implement legislation and created Ipid, both intended to demilitarise the police and bring their work practices in line with democratic values. But these efforts have been rejected by police management, who claimed that expanded oversight prevents them from stopping violent crime. This argument blames the police’s historical ineptitude at crime control on democracy itself, rather than on the failures of their institutional culture.

The government pandered to this delusion by adopting a “war on crime” mindset, representing the police as the outgunned good guys who need the gloves taken off to fight the real criminals. This rhetoric also deflected from the government’s failure to improve socioeconomic conditions and reduce the causes of violent crime and public insecurity.

The ANC has also relied on police authoritarianism for its own political ends. In the early 2000s, social movements such as the Treatment Action Campaign and the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign were met with paranoia and hostility by the ANC. Police were deployed to repress and intimidate grassroots activists.

Repression has been accompanied by deepening kleptocracy within the ANC, which intensified in the Jacob Zuma years. Delinquent police have been key in ensuring criminal politicians evade investigation, while some local stations serve as de facto private security for political despots.

Kleptocracy joins in

Opposition parties propose crime policies that would flood the streets with more police without substantively addressing the clear internal failings of the institution. Police brutality is also legitimated by a popular authoritarianism in the mass media and culture that justifies abuse of the impoverished as necessary for maintaining “order” and “respect”.

What these reactionary arguments omit is that the current system of policing is inadequate for ensuring public safety. The police focus its resources on brutalising impoverished communities, while its capacity to investigate complex crimes, such as the construction and trucking mafias or gang violence in the Western Cape, is negligible.

Crime and personal safety are urgent issues that require social interventions, but the Viewfinder database shows the police is itself a major contributor to daily violence and to a culture of state impunity.

Related article:

The South African Left needs to engage with this crisis, to demand accountability for daily police killings and graft and also to challenge the wider authoritarian drift within the state. As shown at a recent demonstration in Mitchells Plain, impoverished communities want both an end to police violence and better public safety from daily criminality.

Activists and theorists in other parts of the world have offered both radical and pragmatic alternatives to bad policing, from increasing the police’s public accountability to building community safety and resilience at a grassroots level.

There are no simple programmatic answers to issues of crime and insecurity, but it is clear that the postapartheid police have failed to break with the racial, class and gender domination that characterised its pre-1994 role. Without a progressive response to the problem of policing, right-wing demagogues and local vigilantes will offer draconian “solutions” that will only advance the decline of democracy.