Desperate asylum seeker languishes in limbo

Junior Ngoy is one of many refugees who were arrested during the Covid-19 pandemic for being undocumented. With refugee reception centres closed since March 2020, he cannot apply for a visa.

Author:

16 February 2022

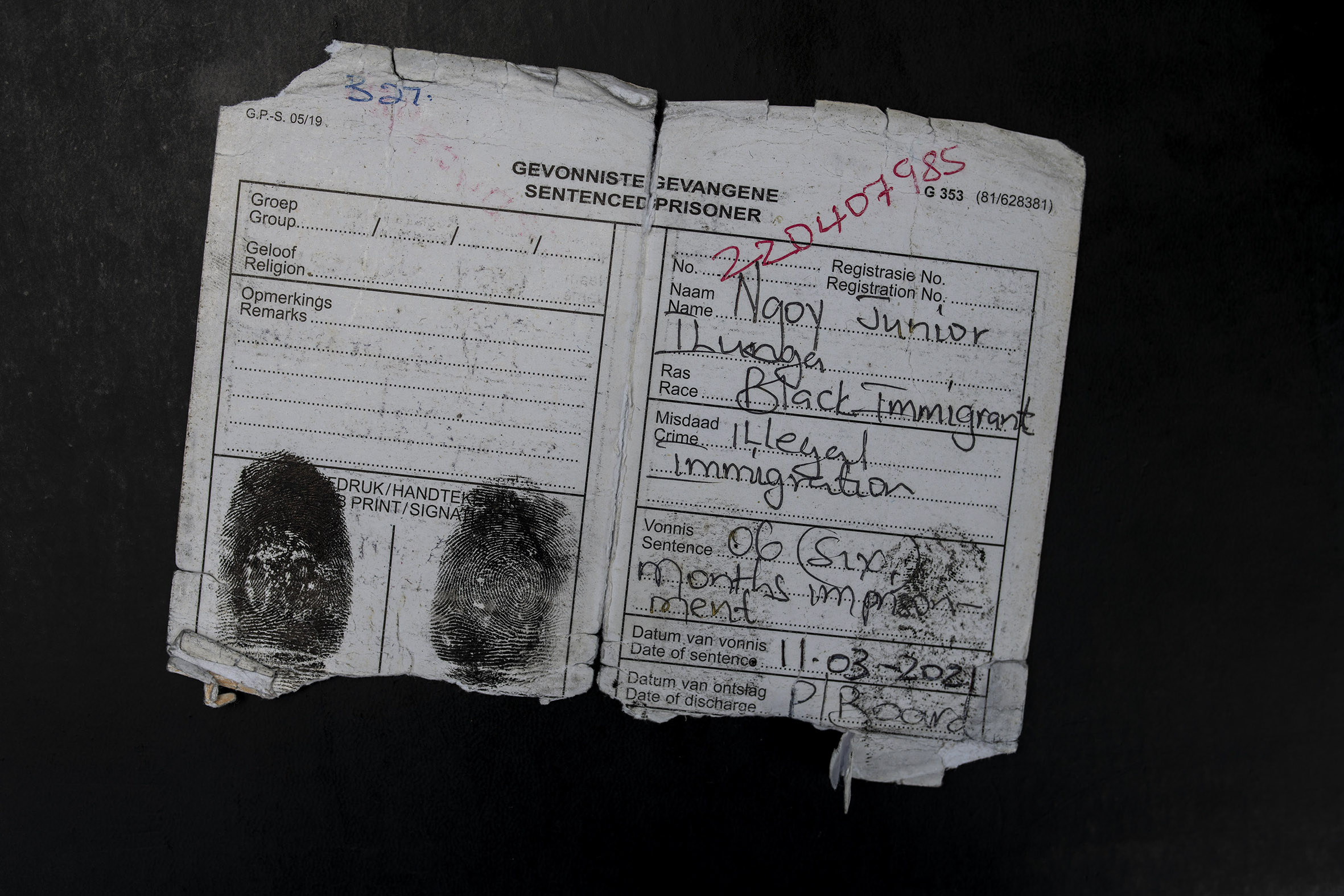

Junior Ilunga Ngoy, 33, saw his son Jason for the first time only when the boy was nearly eight months old. Ngoy was arrested at his house in Germiston in Gauteng’s East Rand in February 2021 when his wife Deborah Kabaso, 27, was heavily pregnant with their first child. He was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for being an “illegal immigrant”.

He had fled the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) after his parents were killed and arrived in South Africa towards the end of 2018. Ngoy says he repeatedly tried to apply for asylum at the Desmond Tutu Refugee Reception Centre in Marabastad, Pretoria, but his efforts were fruitless.

Asylum seekers in South Africa have struggled for years with long queues and having to try repeatedly to apply for asylum. Things got worse when the Covid-19 pandemic hit and the Department of Home Affairs closed reception centres as part of its lockdown measures. That prevented Ngoy from legalising his presence in the country and he remained without documentation until his arrest and sentencing.

“I don’t know what [the police] were checking, but they were checking the paper. They said to my wife ‘if we find the paper, he will come back’,” Ngoy explained.

He was taken to the police station, where he spent the night in a holding cell while his wife was home alone. She did not see him again for almost 10 months because he went to prison and on release was sent to the Lindela Repatriation Centre where undocumented migrants are housed before they are deported. Ngoy was kept for the maximum period of 120 days before being released and reunited with his family.

“Prison was so bad,” he said. “They mixed me with criminals, with someone who commited murder and all those kind of things. It was not easy to adapt to that kind of thing.”

Illustrating the institutional xenophobia that so many migrants experience, his prisoner card classified him as a “Black Immigrant” under the race category, something his lawyers described as “incredibly concerning and … reflective of government institutions’ discriminatory attitude towards migrants”.

But Zandile Mabunda, spokesperson of the Department of Correctional Services, denies that the description is xenophobic, saying there is no intention to discriminate against anyone. “The department’s system is designed as such for record purposes to be able to refer [released prisoners] to home affairs if necessary and for security reasons,” she said.

Scared, hungry and alone

While Ngoy languished in prison, Kabaso was left to fend for herself. She was evicted from the couple’s flat because she could not continue paying the rent. She briefly ended up on the street and lost most of their possessions.

“It was so difficult for me. I was alone and slept on the street,” Kabaso said through tears. “I dream of just living a happy life like everyone else lives. Sometimes I ask why I have to live in these conditions, from the time I was pregnant up until now. I have been through a lot.

“The stress of my husband [being in prison] … sometimes I didn’t know where to sleep. Sometimes you sleep outside, sometimes you don’t have food. And you’re pregnant. It’s been too much,” Kabaso said.

With her husband standing next to her, she describes “a happy life” as one in which they have a safe place to sleep, can buy the food they want and not have to worry about their immigration status. As things stand, they are always filled with fear when moving around.

Related article:

Ngoy says it has been a struggle to “start from scratch again” after losing everything. The family struggle to pay for the small wooden shed they have been renting for R1 500 a month in a backyard in the north of Johannesburg. They have already been threatened with eviction.

“Sometimes I can’t even sleep because I worry about the baby,” said Ngoy. “You see this thing [the house]? It gets cold and then the baby gets sick. People should not live like this. We were not supposed to stay like this. It is cold, too cold. When you feel the skin of the baby it is cold.”

Jessica Lawrence, Ngoy’s legal counsel at Lawyers for Human Rights, says Ngoy’s failure to apply successfully for asylum after his arrival in 2018 makes his case weak, but he has the right to try again. However, he is at further risk of arrest and detention from officials because he is undocumented. The fear of being rearrested means Ngoy and his family barely leave the property and they don’t ever venture too far from home.

A game of semantics

The seemingly indefinite closure of the refugee reception centres have forced many new arrivals hoping to apply for asylum to remain undocumented for the past two years. “The problem of people being undocumented was not triggered by the closure of the refugee reception offices,” said Siya Qoza, spokesperson for Minister of Home Affairs Aaron Motsoaledi. “It was there long before Covid-19. At any rate, not all undocumented persons are asylum seekers. Secondly, nobody ever said the offices will be closed indefinitely.”

Qoza insists that the refugee offices have been closed only temporarily. “You consistently refer to the indefinite closure of the offices. Kindly refer us to any decision by the department where the word indefinite was used,” he said.

Related article:

“The closure has nothing to do with anybody’s thinking but is a consequence imposed on us by the global pandemic. Services were disrupted worldwide and no country is offering services as it used to when there was no Covid-19.”

He says the decision to “temporarily” close the offices was taken “to give the department the best chance of saving the lives of persons” in South Africa. And though he claims the department allows for online asylum seeker visa applications, there is no such link or information on its website. A statement issued on 6 May 2021 provides only email addresses to extend existing visas.

Hardened attitudes

Lawrence says Lawyers for Human Rights has received many requests for help from newcomers who cannot apply for asylum. “Asylum seekers who are new to South Africa or arrived during the lockdown have not been able to submit an application for asylum, placing them at risk of arrest, detention and refoulement.

“Currently, the Department of Home Affairs has not indicated when the refugee reception offices will reopen nor has it introduced an online system for lodging an application for asylum,” she confirmed.

She says the department has been introducing more regressive anti-migrant policies, draft bills and laws under the leadership of Motsoaledi. These include the Refugees Amendment Act, which limits to five days the time an asylum seeker has to report to a refugee reception centre.

“Furthermore, through our experience, there has been a shift in the Department of Home Affairs’ attitude towards asylum seekers since his appointment, with officials unashamedly displaying contempt towards non-nationals,” said Lawrence.

“The government’s anti-migrant narrative, which we are seeing in policies, laws and election campaigns, filters down to all government institutions and ultimately government officials, resulting in institutionalised xenophobia and the othering of migrants, specifically Black migrants.

“Classifications like ‘black immigrant’ seek to create a second-class citizen, who in the eyes of the government and certain political parties is less entitled to rights and constitutional protection.”