Derrick Nxumalo’s art finds humour in paradise

Widely collected in South Africa and internationally, the artworks the KwaZulu-Natal visual artist creates are a layered critique of degradation and hope.

Author:

14 September 2021

In a roughly 24m², sparsely furnished enclave at the Kwazulu Natal Society of the Arts (KZNSA) Gallery, visual artist Derrick Nxumalo leans forward and then sits back in his chair as he speaks in circles, tracing his beginnings as a labourer and artist.

He half mocks the ever-hopeful South African democratic project. He muses how corruption continues to plague the country. And then his thoughts circle back to their beginning, again and again, as he speaks of how optimistic utopian speculation and dystopian presents mean further degradation for the cities he studies and indignity for the people who live in them. The architecture of his thinking, unlike his art, is not defined by the linear.

The KZNSA Gallery in Durban is hosting Nxumalo’s Paradise? exhibition. He is speaking about himself and his work in mid-July, as the riots in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng gain momentum. The burning tyres and logs blocking roads, trucks burnt to shells on highways, and looted and incinerated shopping centres contrast starkly with Nxumalo’s iridescently bright works.

Against this wide-eyed reality, Nxumalo is thinking about wakeful dreaming.

“As an artist,” Nxumalo says, “you don’t sleep. It’s like you pretend to sleep. All these pictures are like dreams, they come and pass, come and pass. In the morning, you select and you just do [paint] it. Our leaders haven’t got a dream and a vision of how to satisfy the people of this country. Unfortunately, our government doesn’t want to attend exhibitions in order to see what the people are thinking about, how they feel. This is an expression [of that].”

The politics of perspective

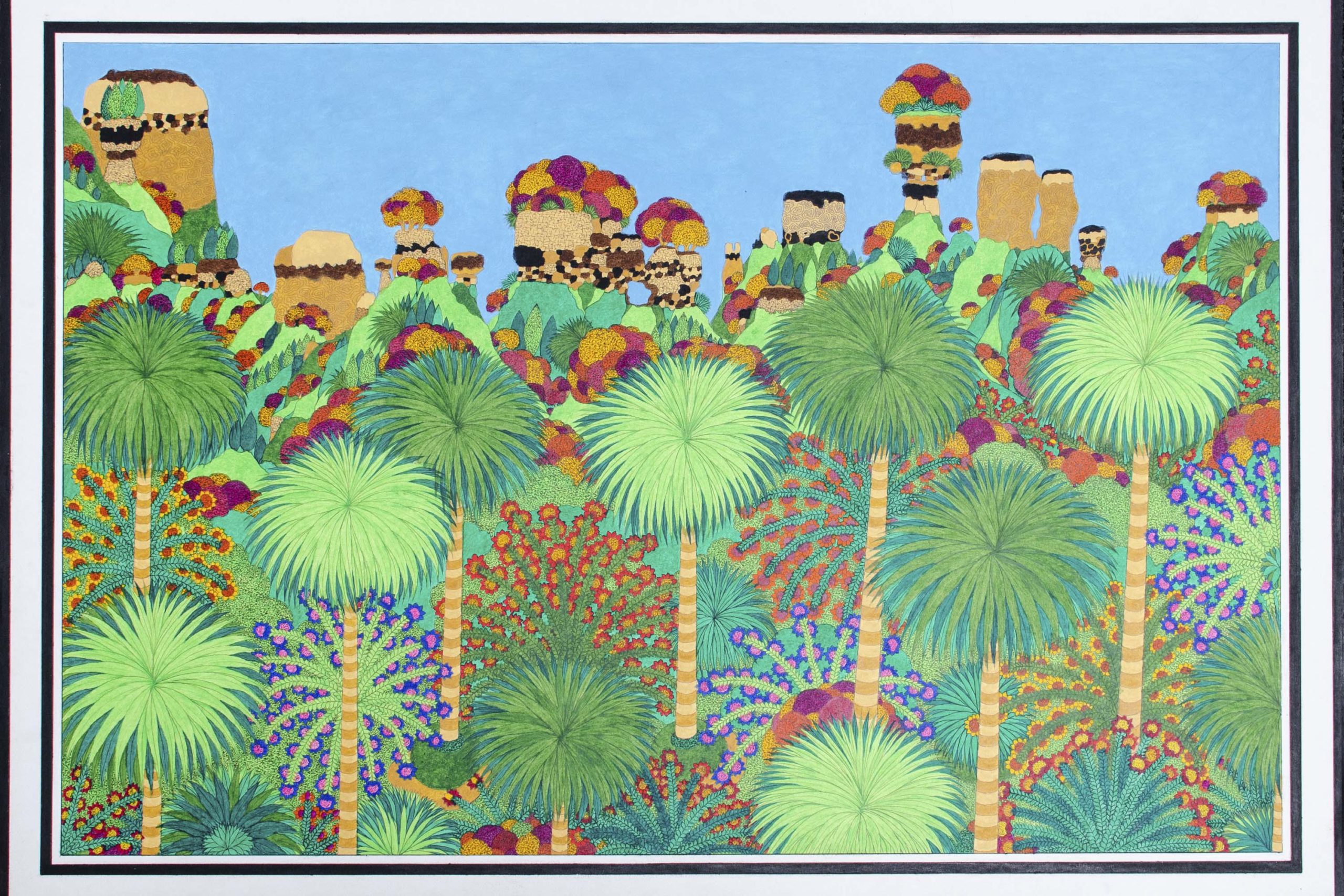

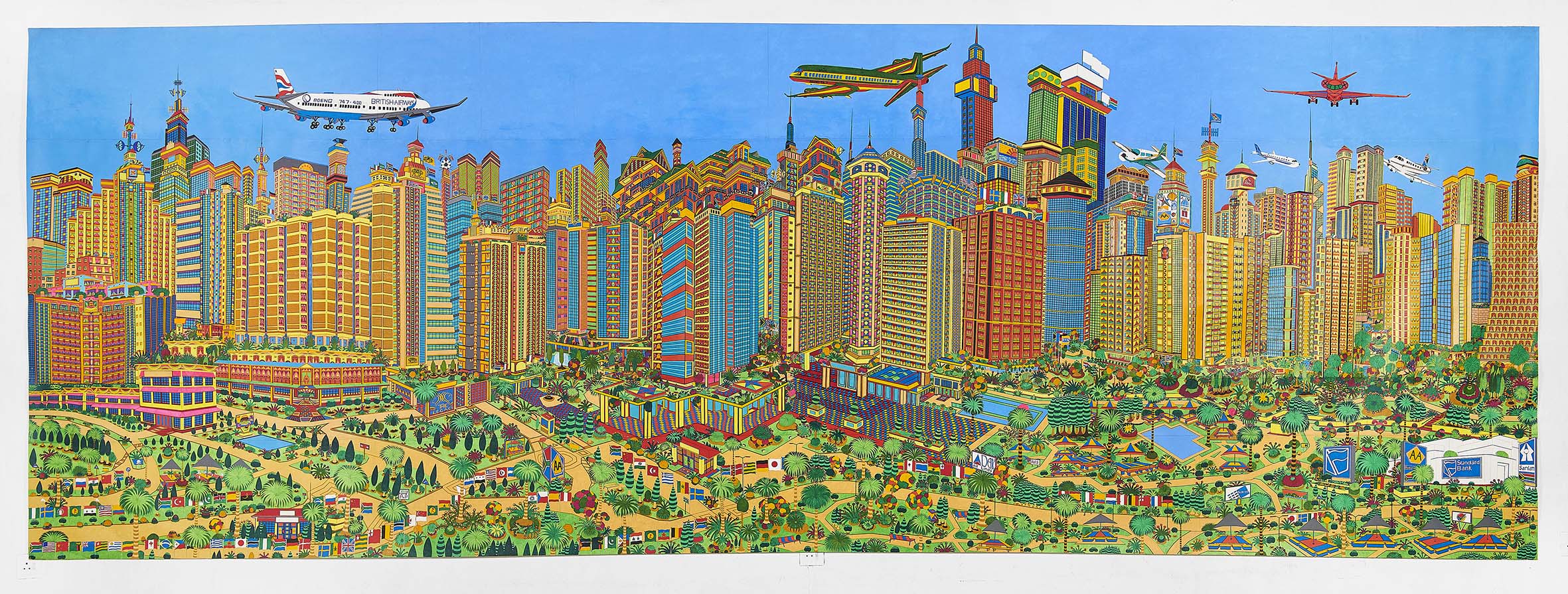

As Nxumalo shifts intermittently while he speaks, so viewers looking at his work shift and reposition themselves. Paradise? is made up of three mural-sized and 23 smaller works in the gallery’s double-storey, three-room exhibition space. The larger works are intricate and show sustained commitment from the artist. From a distance, they are viewed in totality. But the detail coaxes viewers to take a closer look, confirm or dispel a suspicion, make a surprising discovery or gain a new perspective.

One of the three larger works is 20 years in the making, according to Nxumalo, and still not complete. The image is painted from the perspective of someone looking diagonally down at the Durban beachfront and the city immediately beyond it. A multiracial crowd frolics in the water as four menacing characters look on – government officials, says the artist. Logo murals and rooftop billboards litter the tops of skyscrapers, indicating the super-presence of corporate South Africa. From here, the cleanliness and order of the scene is abstract and not lived or experienced intimately.

Less than 30 minutes’ walk away is the suburb of Berea, where Nxumalo once worked as a gardener on Musgrave Road.

“There’s almost this invisible voyeur that’s looking into the suburban garden,” says cultural producer and creative industries consultant Russel Hlongwane. “I think it’s how he as a Black man is looking into the garden space or is looking into the suburban home. That’s one of the few ways that he becomes visible. He’s not present in that frame.

“How he is asking us to look at these gardens is the way that he looks at them himself, I think. And the removal of Black folk in that situation says a lot. If anything, it probably reaffirms this suspicion. It definitely speaks to this invisible labour that tends to these pristine places yet are completely invisible and can’t be imagined in those spaces.”

The smaller works also feel more intimate up close, almost invoking portraiture techniques in portraying natural landscapes. But these, too, do not show the domesticity of the city’s households. Instead, white characters are seen stamping their authority and ownership of leisure in these public spaces.

Speculative futures

Paradise? and Nxumalo’s greater body of work interrogate the state of post-democratic dilapidation in Durban (arguably all South African cities) by speculating about a future in which they are meticulously maintained and their presentation is pruned, almost preserved. “The work interprets what I feel is supposed to be in our country,” Nxumalo says. “We are a lucky country because a lot of people want to invest their money here. They invest it and it just disappears. We don’t see what is happening.”

There is more to it. The artist and his praxis challenge a way of understanding both artist and work outside of Western frameworks and norms. Even Afrofuturism, which hypothesises utopian and dystopian African futures, doesn’t quite suffice as a singular point of departure. The quickening moments of Paradise? are when the multiplicity of gazes and perspectives is felt by the viewer. The visceral response carries a tinge of suspicion that the viewer’s limited experience and knowledge of South African society might be derided.

“From my point of view, Derrick shows us part of the South African psyche,” says Greer Valley, a Michaelis School of Fine Art doctoral fellow and co-author of the exhibition statement. “There is parody in the way that that’s been played out. It’s almost a parody of itself, this great South African city. Regardless of everything that we need to focus on in order to get there – [municipal] service provision, access to housing, a transport system that is egalitarian, the real gritty things that make a city work – as South Africans, we often put that stuff aside and want to talk about the idealistic [and] utopian.

“That is a coping mechanism in the face of trauma and a dream deferred. Because Derrick invokes a lot of these nationalist symbols, we’re constantly being confronted with this notion. I think he is trying to be tongue in cheek in showing us that.”

Nxumalo’s complexity is not that he might be playing a game with the viewer without their being privy to it and its rules. It is that he is likely playing multiple games simultaneously with different sets of audiences. As he speaks and moves, you are forced to focus and refocus. As he paints, you are forced to do the same, stepping back and moving closer, gaining new insights every time.

Nxumalo will feature in Off the Grid, an exhibition at the Turbine Art Fair that features mid-career South African artists.