Covid-19 hero: the school cleaner

In this series, New Frame profiles the unsung heroes who have kept the country fed, safe and healthy during the pandemic – like Daria van Sencie, who protected her school over the lockdown.

Author:

7 December 2020

Daria van Sencie, 52, is one of the many heroes who played a critical role in keeping South Africa safe and healthy when the Covid-19 pandemic hit. Van Sencie has been a casual worker for 24 years, but this has not affected her dedication to her job of cleaning up after children at Triomf Primary School, where she works as a general assistant.

The government school in the impoverished community of Bethelsdorp in Port Elizabeth has roughly 1 000 pupils. “I started in 1996, cleaning and running a feeding scheme for the kiddies,” she says. “Those days, I did domestic work in the evenings. Sometimes teachers also hired me privately on weekends to clean. In 2000, new pre-school classes were added, and I painted the walls every day until noon and cleaned the school in the afternoons.”

Van Sencie’s own children, now grown up, attended the school when they were young. She cleans the classrooms, toilets and the administration block. She also does some gardening and general maintenance work. Cleanliness is an important element in the fight against Covid-19, making Van Sencie a critical component of keeping children from Triomf safe.

Related article:

Although she has held this position for 24 years, Van Sencie has never been employed by the Department of Basic Education. She is paid just R1 300 a week from funds raised by the school governing body. Early on in the hard lockdown, this money dried up when parents in the area were retrenched or lost their casual jobs.

Forced to survive only on Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and temporary employer and employee relief scheme payments for three months, Van Sencie was evicted during lockdown because she could not pay rent. It was the second eviction of her adult life.

Van Sencie weeps three times during our interview. The first time is when she tells the story of her lockdown eviction. The second is when she shows us the Wendy House-style home she was forced to erect after being evicted, and the third is when she describes an earlier eviction in 2002.

“When I was evicted in lockdown, I was forced to make a second loan on top of the loan I already had, so I could put a Wendy House up in my late mom’s backyard. I sold koeksisters door to door to survive,” she says.

Leaky houses in the Windy City

Showing us the three-room structure she shares with two of her children and two grandchildren behind the house where her siblings live, Van Sencie cries again. Although the home is new and well built, Port Elizabeth’s notorious winds make it an uncomfortable place to live.

“Living here is disastrous because when the wind blows, there is no sleep, and when it rains, it leaks, and I sleep on a wet bed. But I still go to school every day. I still have the normal smile on my face, and I treat my children [the pupils] and teachers with the utmost dignity and respect,” she says.

Van Sencie went to work during lockdown even though she knew the school governing body would not have the money to pay her. “There was a lot of vandalism happening to other schools. So I wanted to be seen on the premises every day, cleaning and working in the garden to keep visible and to keep bad elements from coming into the school,” she says.

Van Sencie still does not know when she will next be paid. The governing body paid her R100 a week in July. “That was all the school could afford. Then at the end of August as the grade 7s were rolling in, we received R250 in a bank packet for the two weeks we were there, and this came from tuck shop revenue.”

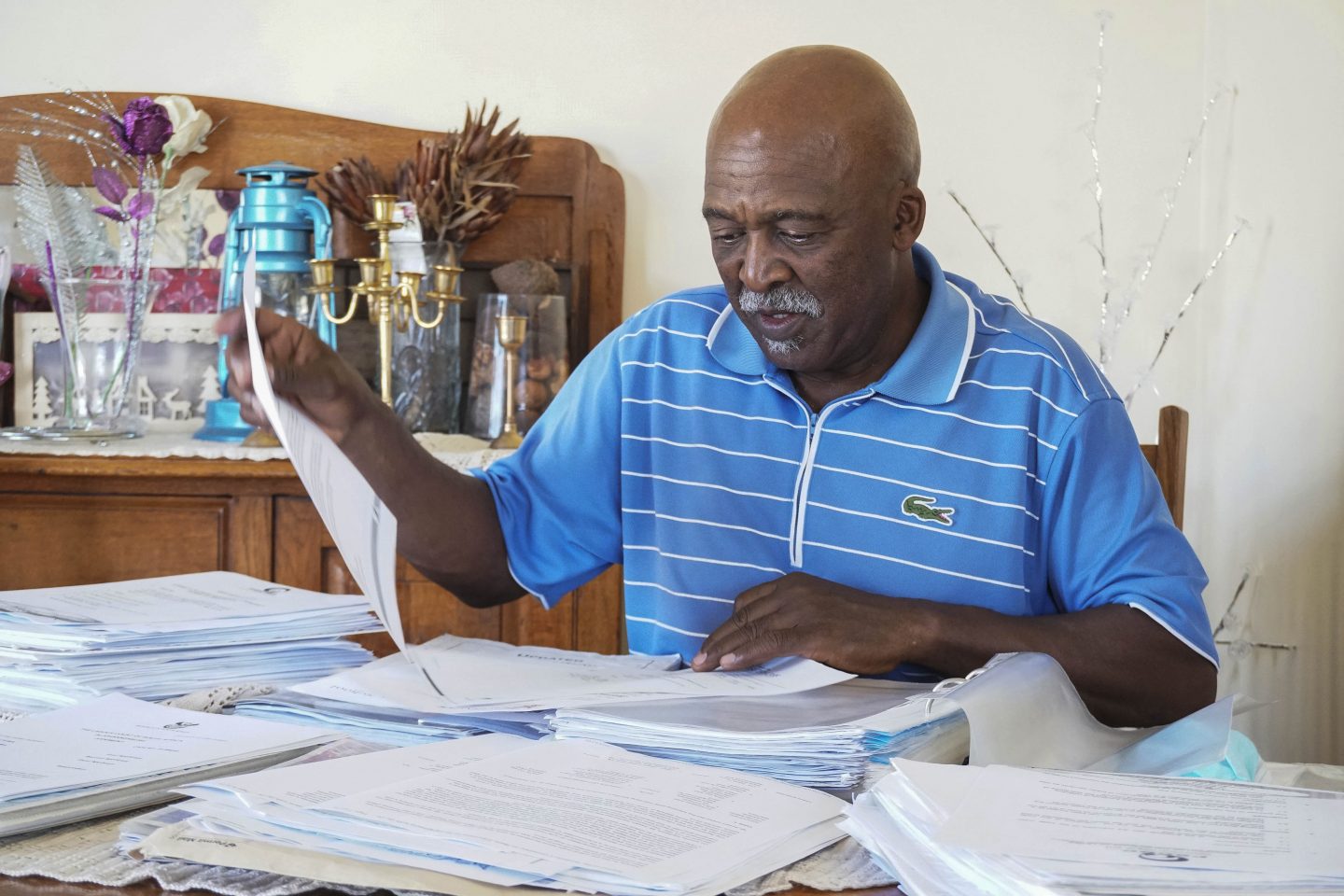

Van Sencie is part of a campaign against casualisation in schools in the area organised by Arthur Frans Grootboom, a former Triomf Primary School science teacher.

Grootboom, who was also forced to work as a casual for four years after the department refused to make him permanent, says there are educators, administrators and other “downtrodden general assistants” like Van Sencie who have no job or income security and who have been campaigning for eight years to be made permanent.

Grootboom says the basic education department oversees a system that is full of problems. It freezes posts and issues a list of available positions at every school – the post provision norms list – but then refuses to fill all the posts. Sometimes, directors in the department fill positions without consulting the school. On top of this, the department does not fund enough general assistant positions.

“At one point, the school was relying on me and a few parents to do all the cleaning. Can you imagine hundreds of young kids using the toilet and no cleaner? It would have been a bad situation within two days if none of us stepped up,” Van Sencie says.

A helping hand from teachers

Schools cannot do without administration staff, enough teachers and cleaners, so the governing bodies have had to “step in and assume the employment and remuneration responsibility of the state. This became an immense financial burden on parents resulting in countless disruptions at schools because of fees charged,” Van Sencie wrote in a letter to the department.

Triomf Primary School is not adequately funded, so parents need to volunteer at the school, even laying concrete slabs in front of the classrooms. They clearly appreciate Van Sencie and greet her warmly when she arrives. She is also valued by the educators, and says, “During lockdown, I survived, barely, thanks to teachers and ex-teachers. They used to collect groceries to see that I had food, some greens and things.”

Related article:

But while it is gratifying to be so appreciated by her community and educator colleagues, the injustice of being overlooked by the basic education department weighs heavily on Van Sencie, because she has never had a regular income and has been unable to live a secure life on her own terms.

“I have no medical aid. I only have UIF. To be very honest, I don’t believe in sick leave and have never taken it. But it would be nice to have medical aid. In 2002, when I was earning only R250 a week, I lost the Wendy House I was staying in and the late principal found a place for me and paid my rent,” Van Sencie says, weeping. “That principal used to give me a bonus out of his pocket every December. He was such a good man.”

“I feel it has been enough now. I have reached the age of 52, and I have no home to call my own. I have had enough of the department’s abuse now. They have been letting the [school governing body] be brokers for them, which is so unfair while everyone else is living a good life.”

President Cyril Ramaphosa recently promised to spend R7 billion creating 300 000 “work opportunities” for young people in the form of teaching assistant positions at schools. But this will not help valuable cleaners such as Van Sencie. She says her basic constitutional rights will “only be realised when school support staff are state-appointed employees and not the lowest tier of workers in the educational sector”.

The Eastern Cape Department of Basic Education did not respond to emails or text messages regarding Van Sencie’s plight.