Coming of age, lost in the forest

Yellowjackets explores environmental and gender horror through a then-and-now storyline that offers insight into the long-term effects of trauma, with a hint of the supernatural.

Author:

17 June 2022

The pilot episode of Yellowjackets, a series now streaming on Showmax, begins with a terrifying image of a teenager being pursued across a frigid winter landscape. Deep in the woods, her pursuers wield spears and are draped head to toe in animal skins. This icy world seems elemental, as if it’s taking place long before recorded human history and organised society.

But as the camera pans to reveal a crashed aeroplane, it’s revealed that this is 1996. The assailants are not Stone Age hunters but the survivors of a New Jersey high school soccer team, whose plane has crashed deep in the remote wilderness while en route to Seattle for the national championship game.

The audacious first season of the American show follows the same characters across two timelines. The 1990s sections track how a highly sympathetic cast of teenage girls gradually descend into warfare and sinister ritual sacrifices as they are trapped for 18 months before being found.

Related article:

The second picks up in 2021, showing how the trauma and dark secrets continue to haunt them as middle-aged women. With uniformly excellent acting across its multigenerational cast, the story expertly handles the long-term effects of post-traumatic stress disorder and violence, showing how the teens of the 1990s became what co-creator Ashley Lyle calls “the fucked up” adults of the present.

The audience is given two distinct, but constantly intertwined, stories. The past section uses tropes of survival horror as the teens are forced to contend with wolves, a lack of food and the coming winter. Over the course of the season, which follows their first months in the wild, the series increasingly hints that the woods are haunted by some entity that wants to keep them trapped there.

While the show is ambiguous about whether this is supernatural or simply the product of psychological distress, the use of dream sequences, hallucinations and occult imagery brilliantly conveys the sense of fragile humans surrounded by forces that are inconceivably ancient, even hostile to us.

The present plotline is an outrageous fusion of character drama and criminal mayhem. In a similar manner to its New Jersey set neighbour The Sopranos, it contrasts the characters’ family lives and everyday adult problems with their depraved private behaviour.

Nature and violence

Taissa as an adult (played by Tawny Cypress) is an up-and-coming liberal politician living a picture-perfect life with her wife and son. But she has a hidden life of dark rituals and ghostly visitations that increasingly threaten to destroy her public persona. Misty (Christina Ricci) presents herself as a caring nurse for the elderly and amateur detective, but she is a sociopath whose adult version is introduced withholding morphine for an elderly patient who got on her bad side.

Shauna (Melanie Lynskey) has mundane drama, such as a strained relationship with her husband, difficult daughter and a mid-life crisis affair with a hipster artist. But these strands converge in a string of blackmails, chase sequences and accidental murder, which show her formidable capacity for ruthlessness.

The series address themes of violence and sexuality in a way that is forthright, but never crass or exploitative. Renewed for a second season and intended to unfold over a five-year arc, one of the main reasons for its artistic success is how it plays with two themes that have fascinated modern creators of horror and dark fantasy: gender and environmental horror.

Related article:

The show’s focus on humans imperilled by the power of nature is especially pertinent in an era of environmental catastrophe. In the 1950s, films such as Them and Godzilla used giant monsters – created by nuclear weapons – as metaphors for the potential consequences of the Cold War arms race.

Later, in the 1970s, a wave of “nature strikes back” pulp films showed humans being punished for not respecting the environment. In the Australian movie Long Weekend (1977), a bickering couple start fires by carelessly throwing cigarettes on the ground and run over a kangaroo, until the wildlife decides to teach them a lesson. The fires that continue to devastate the Australian continent suggest that the film’s message was ahead of its time.

This theme is even more horrifying in the 2020s, when rapacious greed is destroying the natural environment and leading to a grim world of mega disasters and climate instability. In the South African film Gaia (2021), the Tsitsikamma Forest strikes back by producing a plague of dangerous mushrooms, which the ending hints will scour the world of human civilisation.

Environmental warnings

Stories about the mysterious perils of the deep forest have an ancient history. Indigenious people in North America have extensive folklore about the same type of woods that Yellowjackets is set in, which includes the semi-human Sasquatch, or Bigfoot, and shape-shifting and malevolent shamans called skinwalkers.

Rather than being used to make people despise nature, these stories are intended as warnings to respect nature and realise that not everything belongs to or can be controlled by humans. Native American communities are today at the forefront of defending natural spaces from reckless expansion and harmful practices such as oil and gas fracking.

The dual facets of nature, as our life-giver but also potential destroyer, is brilliantly captured in Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997). Set in the feudal past, this fantasy anime film shows the conflict between the ancient gods of the forest and the forces of Irontown, a proto-capitalist industrial society that slashes and burns the wilds with no thought of the consequences.

Related article:

These attacks destabilise a more harmonious natural order and unleash fearsome demons on the human world. The film’s protagonists, which include San, a young woman raised by wolves, are forced to defend the forest against the forces of greed and power.

Even though it’s set in the distant past, Miyazaki’s film has a visceral contemporary relevance. Corporations and governments continue to devastate the environment in pursuit of short-term profit, ignoring the nightmarish ramifications for the near future.

In contrast, the film suggests that we need both an awe for and a healthy fear of the planet, suggesting this will save us by guiding us to ways of life that respect biodiversity and environmental limits. In defending the forest, we are defending ourselves.

Patriarchal fear

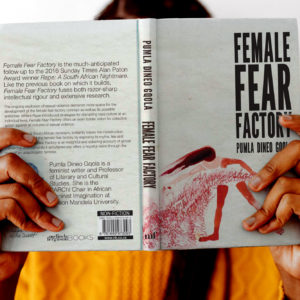

As Silvia Federici writes in her 2004 book Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation, the environmental crisis of today entails specifically gendered forms of domination. She says the ideology that underpinned the beginnings of capitalism in Europe was based on the claim that nature was there to be exploited by men, but so was the autonomy and sexuality of women.

This found cultural expression in a panic about “witches”. Campaigns of burning and persecution were launched against women, and practices such as peasant “wise women” providing medicine to their communities were rebranded as being in league with the devil.

Related article:

The stereotype of women as forest witches – who are often alluring, beautiful and murderous – reflects a paranoid host of reactionary patriarchal fear of matriarchal power. As the teenage Natalie (Sophie Thatcher) points out in Yellowjackets, there is a long history of male scapegoating and projecting their failures on to women.

In modern times, artists have reclaimed the figure of the witch as a “symbol of female strength in both positive and negative ways”. The witch, in this version, is the ultimate anti-patriarchal rebel. The cult 1996 movie The Craft focuses on four alienated high schoolers who form a Wiccan coven in ways that empower but also endanger them. Rather than painting the witch as a threat, it celebrates the idea of finding power in being an outsider.

Real-world witches

This thinking has filtered into real-world activism. In 1968, members of a New York socialist feminist group formed Witch, the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell. Using sarcasm and irony to challenge greed and warmongering, members conducted theatrical protests such as placing “hexes” on Wall Street as “a symbol of patriarchal, slave holding power”. Witch also challenged how patriarchal definitions of family were used to force women into subordinate and restricted roles, and impeded their potential as liberated individuals.

The theme is explored in director Robert Eggers’ The Witch: A New England Folktale (2015). In early colonial America, the family of teenager Tomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) are forced out of their settlement after a religious schism. And the deep woods they live in are indeed surrounded by a coven of witches who pray on the isolated family.

Related article:

But rather than being innocent victims, the film shows Tomasin’s parents as ignorant and cruel religious zealots. They blame their misfortunes on their kind-hearted and independent daughter, and in the end their adherence to harsh patriarchal standards destroys them as much as the occult forces around them.

In the film’s closing scene – which has become an iconic image of contemporary horror – Tomasin leaves the bloody wreckage of her family to join the witches of the woods. Dancing around a bonfire, they began to float above the lush treeline as she responds not with fear but gleeful laughter.