Changing the script of sport as ‘just a game’

Sport is all about the hard work and talent that enable athletes to make it to the top, right? Wrong. Beneath this neutral veneer lie narratives built on racism, sexism and dangerous nationalism.

Author:

21 May 2021

In the midst of the most devastating contemporary health pandemic, in a country where the death rate from Covid-19 outnumbered every other nation’s, where racist implications resulted in Black Americans dying at twice the rate of white Americans and Native Americans’ death rate was the highest, 25 000 supporters congregated at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida, to watch the Super Bowl on 2 February.

The importance, salience and content of the Super Bowl in the United States depend on who you ask. The championship game of the National Football League (NFL) is as much about performance as it is about the sport itself. There are contingencies of fans, viewers and consumers who are invested in the contest, just as there are legions of fans, viewers and consumers who are invested in the tradition of the famous halftime show.

The Super Bowl averages at least 100 million viewers each year and has an incredible economy surrounding it. To put it into perspective, advertising space during the Super Bowl costs $5.6 million per 30 seconds, about $4 million is spent on gambling, $14.8 billion is spent nationally on food and drinks, and cities bid upwards of $5 million to host the game.

The staggering figures explain why the NFL spectacle has to go ahead, pandemic or not. But what function does sport, specifically the Super Bowl, play in the American political landscape? Overall, what role does a national sport play when it comes to the maintenance of any nation state?

Sport has long been a place of storytelling. Or rather, of myth-making in which there are prescribed roles and characters, conversations to have, things to cheer for, pedestrian rules and occurrences to be annoyed by, and ideas and outfits to buy. And when looking at the legacy and trajectory of sport in the US, watching it is framed and experienced as “paradise” where “everything that is going on lately” – a euphemism for any challenge to the status quo – is escapable. Numerous scholars of sport note that this kind of political immunity is a result of sport’s privatised nature and the ideals of what privatisation is supposed to bring, which frequently is meritocracy.

Meritocracy and “hard work” permeate the foundations and expression of sport, and therefore “neutral zones” are established. Politicising a sport doesn’t have a place if it is solely about physical virtue, performance and egalitarianism. In other words, “it’s just a game”.

The US playbook

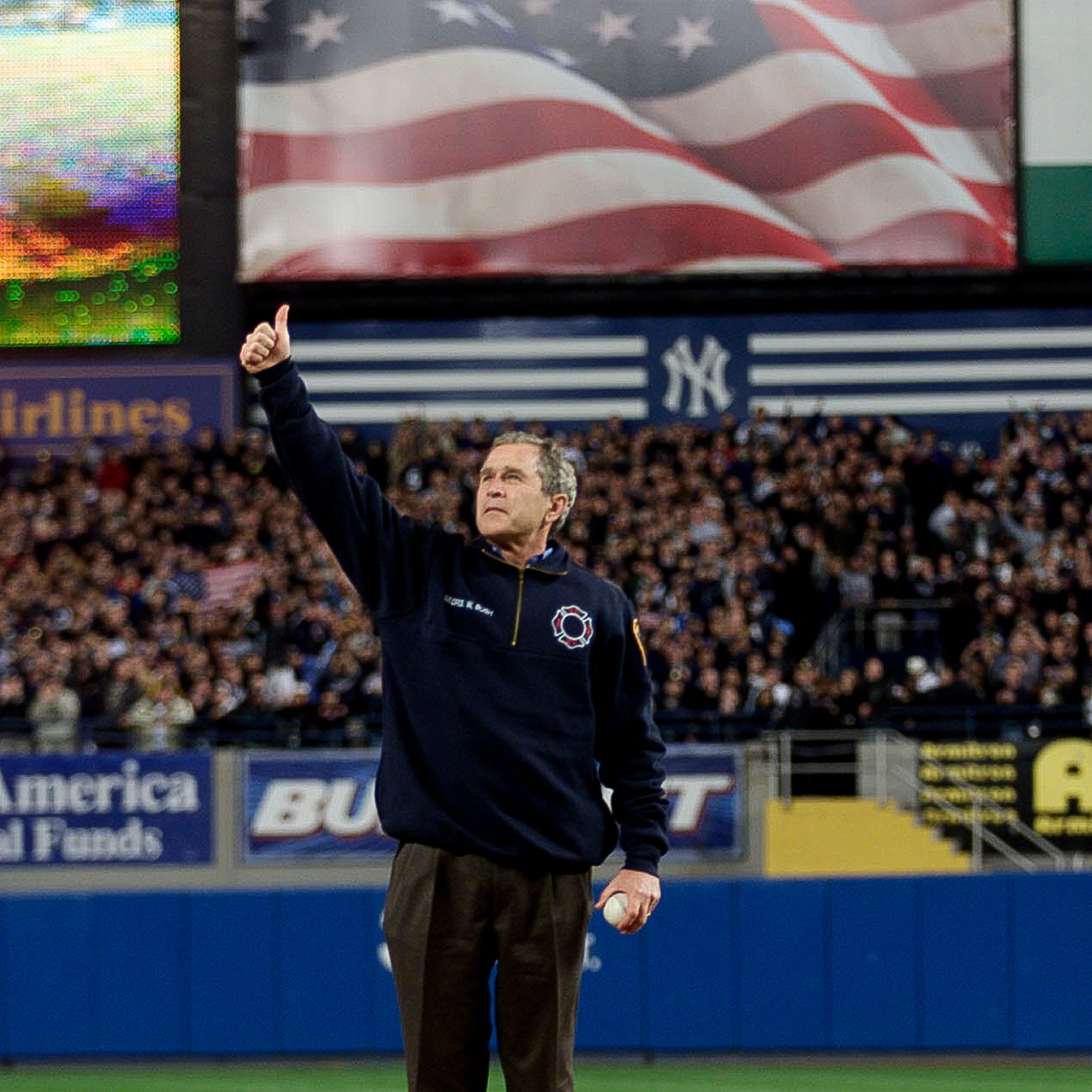

Built around the neutral zones of any given baseball, basketball or American football game is an atmosphere of ritual. The symbolism of sport in the US is deeply entangled with the symbolism of America itself and the scripts of exceptionalism, nationalism and patriotism that are indoctrinated in many Americans from a young age.

From your local middle-school volleyball game to the Super Bowl, games are consecrated with the national anthem and a pledge of allegiance to the American flag. This repetition of a song that was written about preserving slavery normalises the American narative of a kind of revolution and liberty that is defined, written and accessed by whiteness and white people.

This ritual also solidifies American exceptionalism because of the sentiments of reverence, honour and sacrifice that are woven into pledging allegiance to the flag. This then legitimises the police and the military as respected defenders of an American liberty and democracy who are protecting “the best nation on earth”, which is always “under threat” from things like communism, terrorism, immigration and so on.

Related article:

American exceptionalism is a selective kind of amnesia and obscures what writer and scholar Richard Slotkin refers to as one of America’s long-standing practices, namely “regeneration through violence”.

In many ways, the need for sport is a need to tune out. Sport offers a script of escape. Sport also provides a script for capitalism, with entire multimillion-dollar economies functioning around its production and media coverage. These economies also create devastating ecological and spatial issues.

Hosting the Fifa World Cup in 2014 resulted in massive displacement and labour exploitation in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In South Africa, the Gautrain was launched and upgrades to Cape Town’s metro rail were done in time for the 2010 Fifa World Cup. But the implications of these “innovations” and upgrades are resoundingly colonial in that an international audience is catered to in their inception and continuing use. Take, for example, the implementation of a dress code that doesn’t allow hoodies to be worn on the Gautrain.

Red, white and blue for whom?

In their book As Black as Resistance, Zoé Samudzi and William C Anderson assert that Black Americans are not American but rather citizens of a settler colony. This calculated and systemic lack of access to citizenship for Black people is highly observable through the realm of sport, affirming the story and practice of racism in the US.

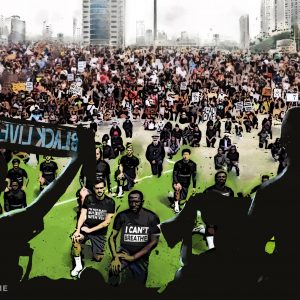

Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of this is when San Francisco 49ers’ quarterback Colin Kaepernick began kneeling in 2016 as the national anthem was played. When asked why he did it, he said: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of colour.”

What followed was a media frenzy that lasted for months. Across the biggest media platforms and the political spectrum, commentators and journalists began discussing how legitimate this protest was. Arguments ran the gamut of “if you hate it here so much, leave (á la go back to Africa)” and “how are you oppressed if you make a million-dollar salary and Barack Obama is president?” to “you are disrespecting the troops and those who died for this country”. At a political rally in 2017, then-president Donald Trump referred to those who protested in a similar fashion as “sons of bitches”.

While all these arguments failed to grasp what Kaepernick was seriously grappling with, namely the long-standing state-sanctioned murder of Black people, what they did show is that the script of sport is fragile and that the nationalism of the US seeks to obliterate anything that points out the truth of violence being the country’s first – and often only – language. We see athletes like Kaepernick five years later still being blackballed and effectively shut out of the NFL and others, particularly Black female athletes, striking out and receiving similar kinds of backlash.

In South Africa, there is also an observable kind of nationalism that sport tries to achieve. Following the 2019 Rugby World Cup victory, the loose and somewhat lukewarm grasps at Rainbow Nation-building were expressed through the media in sentiments that tried to frame the moment as a needed revival of hope, something that presented a forward momentum against the backdrop of a “disillusioned” South Africa.

The 1995, 2007 and 2019 victories differ greatly in how they are remembered and their context, but a significant theme is the proposition that unity is within reach and rugby can show us the fruits of everyone’s unassigned but required labour.

The politics of hope

This dangerous sentiment is poignantly countered by writer Lindiwe Mngxitama when she writes: “One could argue that the politics and politicisation of hope, or what Lauren Berlant names as a ‘cruel optimism’, have been used as organising tools of social pacification since water has been wet.” From here, it can be understood how deflating an emotion hope is, how ambiguous the requisites for the future are, and how consensus requires the silencing of narratives that centre the indignity which colonialism produces every day.

The positioning of rugby as an available interlocutor or connector of a “divided nation” severely undermines what created – and continues to create – the division in the first place. It is pinning an almost random potential of what South Africa could be against a lived reality that lacks access to dignity for many people in the country. Like a plastic fork breaking underneath the weight of hearty food, it cannot do any heavy lifting.

Writer and essayist Sisonke Msimang also made important observations in interrogating the Rainbow Nation ideals that were expressed by the editor-in-chief of News24, Adriaan Basson, following the Springboks’ victory in Japan. In his op-ed titled “The Rainbow Nation Reloaded – Let’s Not Mess It Up Again”, Basson wrote that there were lessons to learn such as “nothing beats hard work” and “champion diversity; it makes us stronger”. He also noted that there was an issue of polarisation, with “the emergence of organisations like AfriForum, the EFF and BLF [which] actively promote polarisation between racial groups to drive membership and votes”.

What Msimang notes from this is that the Rainbow Nation is a costly project. It is one that seeks to flatten out “prejudicies” and violence to a point where the white supremacist ethnostate that AfriForum desires is comparable to patriarchal (and misplaced) iterations of Black politics.

Making race and gender

In addition to fortifying amnesiac myths about the potential of any given country, international sports arenas are also places of racialisation and gendering. Caster Semenya, the South African track star, has been subjected to numerous investigations over the past 10 years by World Athletics, formerly the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).

These investigations are motivated by incredibly rigid, violent and unreliable ideas of sex and gender and performance, and they ultimately are an enforcement of these limited ideas of normative sexual and gender identities.

At the beginning of her career in 2009, Semenya was subjected to tests of her chromosome and testosterone levels to verify her gender. She took testosterone-suppressing drugs from 2010 to 2015 under the conditions of the IAAF. And in 2019, World Athletics declared that Semenya was “biologically male” with a “female” gender identity.

Related article:

This deeply private-turned-public policing demonstrates a level of violence and violation that is unthinkable. It is a depersonalisation that is institutionalised as “regulation” based on ideas of science that are not only inaccurate, but also deeply colonial in the organisation and differentiation of sex as well as gender.

Semenya’s queer identity plays a large role in the discrimination against her. But she is Black, queer and a woman – all identities that society deems to be of lesser value and that therefore invite more suspicion and attract more violence to her. While there is seemingly a kind of politically correct distinction made between gender identity and sex, scholars like Oyèrónké Oyěwùmí point out that sex and gender are on the same side of the coin because both essentialise difference.

“Consequently, those in positions of power find it imperative to establish their superior biology as a way of affirming their privilege and dominance over ‘Others’. Those who are different are seen as genetically inferior, and this, in turn, is used to account for their disadvantaged social positions,” Oyěwùmí writes.

In interrogating the experience of those gendered and raced as Black women in gymnastics, Nomali Minenhle Cele reflected on fine artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s series Gymnasium. Cele writes that Black female athletes, the subject of Nkosi’s artworks, are often massively doubted and then, once they are recognised as excellent, become subjects of suspicion. This is incredibly applicable when Serena Williams’ career is considered in terms of the amount of racist, sexist and often transphobic scrutiny to which she has been subjected.

Breaking the code

In 2018 alone, Williams was subject to two significant kinds of policing or scripting. After competing in the French Open, a tournament she has won on three occasions, in a black jumpsuit, or as she called it, her catsuit, French Tennis Federation president Bernard Giudicelli banned her from wearing it again because it broke the “dress code” of the tournament. It was an arbitrary yet targeted decision against the look and movement of a muscular Black woman.

Later in the same year, an Australian newspaper, The Herald Sun, released a cartoon of Williams that drew many parallels to Jim Crow and colonial imagery. Her body was depicted as “oversized”, attempting to emphasise how “unwomanly” her figure is. As such, transphobic commentary aimed at Black cis women about their “manly” form reinforces ideas of smallness, fragility and inferiority in “female” forms, but also aims violence at those whose appearance does not fit into a prescribed box.

Additionally, in the context of sports media, commentators and journalists engage in the maintenance and reproduction of racialised and gendered discourse. For example, Black male athletes are often referred to as “naturally gifted” and “strong”, while their white counterparts are regarded as “intelligent” and “hard-working”. The underpinning of what could be read as admiration is more so a rootedness in the fetishisation of the Black body, a further extension of colonial imagination.

Sport presents an incredibly intricate place in which to view the world and how the world is made up and remade on a regular basis. The narrative of hard work and physical ability and the overall notion of a game provide the basis for an outlet that is accessible to many. But the silencing of the political implications of how some of us show up at the arena or the signing ceremony and get shut out is a reality that needs changing.