Cara Stacey wants to move the music forward

The Standard Bank Young Artist award winner finds working with other musicians inspiring, despite the mainstream establishment view that collective work suppresses individuality.

Author:

4 November 2021

“It was a total shock,” says composer and multi-instrumentalist Cara Stacey about her selection as the 2022 Standard Bank Young Artist for Music. “And I feel super lucky. I’ve never made strategic career choices within music. I’ve followed what interests me, and in relation to contexts like this I’ve often felt I might not be mainstream enough.”

“Mainstream” certainly isn’t the first word you’d apply to Stacey. Her many instruments start conventionally enough with piano, but also include African indigenous bows such as umhrube, uhadi and makoyane, as well as explorations of electronica and collaborations with traditional, jazz and classical players and visual artists such as Mzwandile Buthelezi.

Stacey was born in South Africa but grew up in eSwatini, where she learned to play the piano and initially seemed set on a career in classical music. It was at the University of Cape Town (UCT) that what she describes as the first major turning point in her musical development occurred. “Up to that point I’d been trying to be a classical pianist, although I wasn’t sure what my eventual career would look like. The choices seemed to be teacher or concert pianist.

“But during my undergraduate studies I had lessons with [Amampondo leader and indigenous instrument master] Dizu Plaatjies and with him, different parts of my musicianship started to bloom.

“His openness – the way he pushed me to contribute my own creativity – gave me a comfort with performing I’d never had before. I could modify and rearrange. Playing these instruments is about your own body and can’t be taught prescriptively. You have to find your own space with other players. I’d never considered those ways of music-making and being on stage before.”

Creating in collaboration

Since those classes with Plaatjies, Stacey has studied with mbira player Tinashe Chidanyika, sabar player Modou Diouf and other teachers. Shaping creative spaces collectively with co-players, rather than pursuing solo success, has been a compass point for Stacey’s musical direction.

At the personal level, that’s reflected in her relationships with notable musicians, for example Lungiswa Plaatjies, Mozambican percussionist Matchume Zango, or bassist Shane Cooper offering advice on electronic remixes.

Stacey talks with warmth about her work with violinist Galina Juritz, for example on the recent album Like the Grass. They studied together at UCT, then met up again in Europe and worked together, “and we’ve really pushed one another in creative ways. I send her ideas for comment; she’s equally accepting of my inputs.”

Related podcast:

More broadly, a collective approach has characterised many of the projects in which she’s been involved. She was, for example, an early member of South Africa’s Women’s Music Collective with composer Clare Loveday, a founder of the Arum performance group and a member of Sarathy Korwar’s Pergola Project, as well as Plaatjies’ Night Light Collective, among others. Creating collectively has given Stacey “the comfort to take creative risks. I’ve always surprised myself when I had the courage to try something new, and part of the support structure for that is knowing I can run things by the people around me.”

She acknowledges that the mainstream establishment often views collective work as suppressing individuality, but she finds the opposite result. “Sure, there’s been feedback that was uncomfortable, but even if it’s hard to take at first you always learn from it and your voice strengthens… Maybe the conventional hesitancy over group working needs to be updated?”

Interrogating composition

That’s as true of composing as playing. In the classical milieu, ideas of the composer as a hero working alone in his garret persist. “It’s surprising how many people want to cling on to that idea,” says Stacey. “Neither my methods nor my aesthetics fit there, and a big part of my move towards African indigenous instruments was opening up to other ways of composing.” Stacey’s master’s dissertation documented traditional bow players in eSwatini as composers “in the true sense. People who create new music, whether or not they notate it.”

Stacey says anyone who can make musical sounds can compose, and alludes to the work of United States Diné (Navajo) musician Raven Chacon, who took string quartets into schools on First Nations reservations and got the children to compose for them. She feels similar initiatives would work in South Africa too, were it not for hidebound attitudes such as “the assumption that you can’t really be a composer until you’ve got your PhD, preferably overseas”.

Interrogating such attitudes, says Stacey, is essential in decolonising the curriculum. Holding a handful of music degrees, from UCT and the School of Oriental and African Studies as well as Edinburgh University, and currently a senior lecturer in African music at North-West University, she has seen first-hand the gap between theory and practice that often prevails.

“Realising how much South Africa is a musical society and what our students bring [to learning music] is discussed at a theory level. But it’s often acknowledged in a box. It doesn’t get practical application in terms of which instruments are valued, or who gets to teach music.”

Conversations on identity

Surely, however, the question of appropriation arises when a white player such as Stacey garners accolades on African indigenous instruments? “Surprisingly, that conversation doesn’t come up as often as it should,” she says. “But I think about it every day when I’m making artistic decisions. I see myself as a multi-instrumentalist and I needed to know how it felt to play certain instruments before I could compose for them. But I have a community and I try to direct attention to the whole community of indigenous instrument players that I’m part of.

“I’ll never be someone like Lungiswa Plaatjies. She’s rooted in her indigenous knowledge and spirituality, and I could never take up that space. Mine’s a different space, composing for the widest palette of sounds and textures. As for thinking about how I can share around… Well, that’s how the people I learned from taught me. They’ve kicked my butt about it and I’m grateful. I can never not be aware of those conversations.”

Another thought strikes her. “Actually, if I was just playing Chopin in Africa today, there are important conversations to be had about the why and how of that too…” Stacey points to the way conversations around identity, race and privilege are shifting even in classical music, citing the address given by George Lewis at this year’s South African Society for Research in Music conference.

Related article:

Gender, too, impacts these contexts. Stacey is a little surprised by where that has and hasn’t cropped up. “Partly, I think in a lot of the small experimental music spaces where I work, you do already find many more women and people of colour.” But she hears what she calls “the backward conversations” these days most often “in South Africa’s big-city jazz scenes. There seem to be new power structures emerging reminiscent of the old classical establishment at its worst, a slightly sociopathic view of jazz as something you have to be ‘tough’ enough for. That comes out as ‘there just aren’t enough good women players around’, the same thing the classical establishment said until very recently about composers of colour.

“It’s disappointing those conversations – many of them with players whose musicianship I really admire – are so defensive, rather than about what they could do to facilitate more women’s participation.”

Redressing imbalances

The Standard Bank Young Artist award occupies a unique space in South Africa’s music landscape, and Stacey feels it has a role to play in redressing such imbalances. She’s grabbing the chance it offers to “jump into collaborations I haven’t previously had time or resources for”, taking voice lessons and working with Loveday to “dust up” her scored composition technique.

On those foundations she’ll be creating works that bring together her three musical worlds: improvisation, indigenous music and electronica, including a new collaboration with Zango. Stacey hopes her award represents part of “a transition” towards more openness in the music category. “Up to now there’s been no space for indigenous instrument players and composers. It’s long overdue that we make real all this talk about acknowledging indigenous knowledge systems.”

A Cara Stacey discography

2015 debut album Things That Grow with Shabaka Hutchings

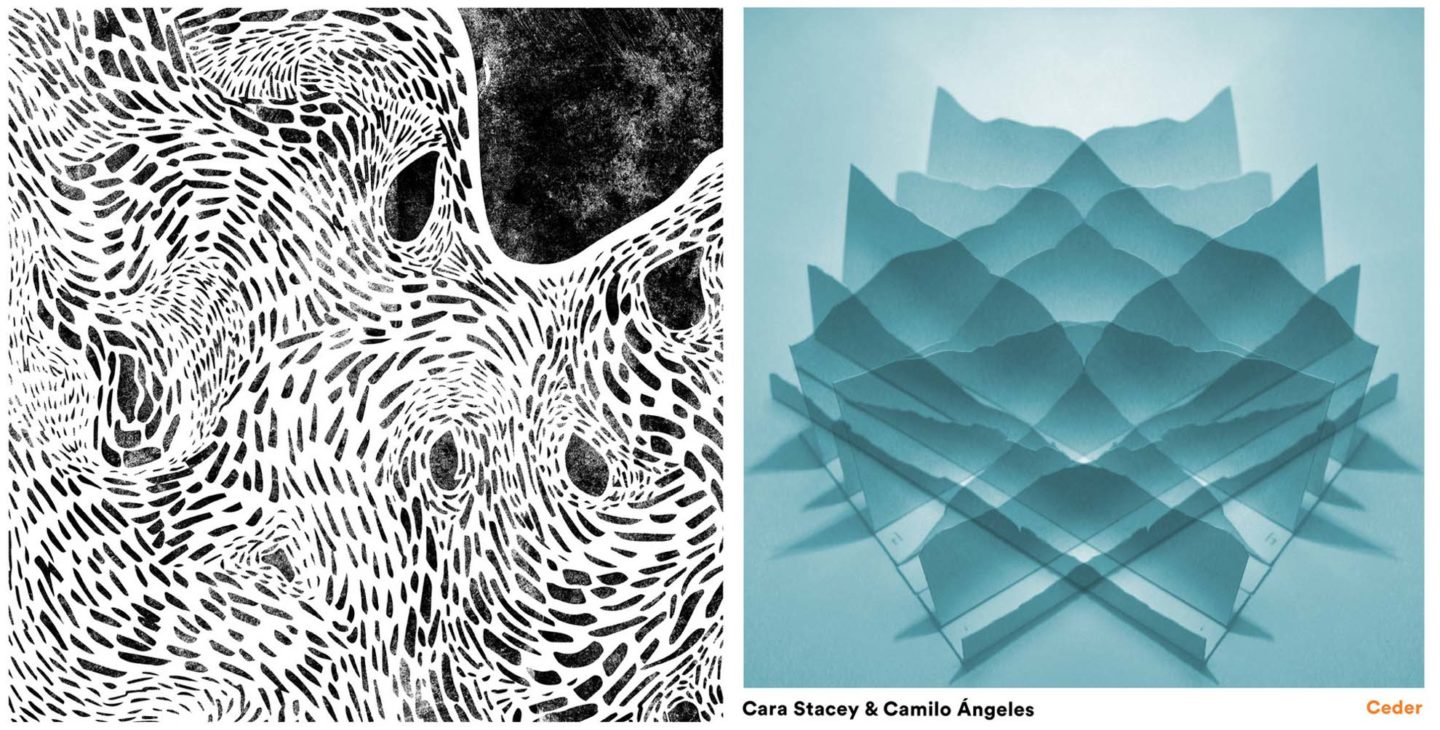

2018 Ceder with Camilo Angeles

2020 Like the Grass by Stacey Juritz Ravens Keller

2021 The Texture of Silence with Keenan Ahrends and Mzwandile Buthelezi (self-released as As in the Sun, So in the Rain)