Can hateful and abusive podcasts be stopped in SA?

Podcasts are becoming increasingly popular in South Africa, but what does accountability look like for a medium that falls outside traditional broadcasting regulations?

Author:

23 March 2022

Media personality and entrepreneur Bonang Matheba welcomed a judgment in late January that ruled in her favour after she sued podcaster and co-host of Everything SA Music Rea Gopane for defamation. During an episode of his podcast in May 2021, Gopane alleged that Matheba had introduced rapper AKA to cocaine.

Despite having been given the chance to apologise and retract his statements twice by Matheba’s lawyers, Gopane refused. He was ordered to pay R300 000 in damages. Matheba released a statement shortly after the ruling explaining that people such as Gopane need to realise that there are “consequences for abusing public platforms to defame and humiliate others”. This is the crux of the issue of regulating podcasts.

The chart-toppers in this form are influential and usually men. Take American podcaster Joe Rogan, whose show, The Joe Rogan Experience, was bought by Spotify for $100 million in 2020. Earlier this year, Rogan received a backlash for spreading Covid-19 misinformation. Musicians have banded together to remove their music from Spotify in protest. In response, the streaming platform put an advisory warning on any content with Covid information, but it has refused to change any of its policies because of one creator.

Related article:

Gopane is certainly not the only South African podcaster in hot water for his statements. No stranger to dominating headlines is MacG, the host of Podcast and Chill with MacG, who has a brash, uninhibited hosting style. During his interview with American singer Ari Lennox, MacG used explicit language to probe Lennox about her sex life in what he said was a reference to one of her lyrics. She said the question, which she described as “creepy”, made her feel ambushed and led to her decision to refrain from doing interviews altogether. Moreover, Lennox further claimed that MacG’s team had agreed to remove the part of the podcast that included that specific question but instead used it as a promo. This was a move that on a regulated traditional broadcasting medium would have been grounds to go to the ombudsman.

When speaking about issues of race, Black people experience subtle forms of racism that are often difficult to name. In a similar way, women experience harassment on these unregulated platforms. At the heart of the conversation about MacG’s podcast is acknowledging that inflammatory and derogatory statements about women and queer people on public platforms perpetuate the harm that is often already an everyday reality for them.

This issue is a reflection of larger social problems. But in a country with an unrelenting scourge of gender-based violence, rape and femicide as well as escalating homophobic violence and killings, what podcasters say matters a great deal.

Accountability in a grey area

The Broadcasting Complaints Commission of South Africa (BCCSA) ensures that both public and privately owned television and radio broadcasters adhere to a code of conduct that prohibits the use of offensive and discriminatory language, displays of gratuitous violence and hate speech. Matters involving accusations of hate speech can be escalated to the South African Human Rights Commission.

The Press Council of South Africa, the accountability body for print and online media, tries to uphold journalistic ethics and standards in the country. But publications must be members of the council to be held to the code of ethics. In the case of podcasters, many aren’t journalists.

When asked if it would explore the inclusion of podcasting within its regulatory jurisdiction in the future, or if it was aware of an arm of broadcasting regulation that would, the BCCSA said it had no comment.

Podcasts, which exist outside traditional structures, are not regulated in the same way as other media and broadcasting. This means there is more room for both play – hosts can, for example, freely use bad language – and for abuse. Of course, as Gopane found, podcasts are not immune to legal processes associated with defamation and hate speech. But the form largely exists outside formal accountability frameworks.

Related article:

Jeremy Nell, the cartoonist who continues to defend his comparison of white historical land theft with Black rape, has a public platform in his podcast Jerm Warfare, in which he speaks about fighting the “thought police” in a world that is an “unsafe space for liberal dogma”. How do we hold him to account – more especially when he utilises block-chain technology to spread his content over decentralised networks?

What’s more, Nell is a strong right-wing proponent, although he oftens denies this, and believes himself to be a kind of Robin Hood who is constantly being persecuted by leftists pushing political correctness. Writer Christopher McMichael aptly describes Nell, who engages in climate change denialism and anti-immigrant messaging, as holding a world-view that has “a deep suspicion and hatred of social egalitarianism, liberation and progress” and a loathing for “anyone who is trying to make the world fairer or better”.

Or take, for instance, Gareth Cliff’s Burning Platform podcast, which made headlines after an episode in which he described member of the One South Africa Movement Mudzuli Rakhivhane’s experiences of racism as “anecdotal and unimportant”. Nando’s, the podcast sponsor, ended its relationship with Cliff shortly after the episode aired. Men like Cliff enjoy being perceived as serious commentators and are afforded legitimacy by mainstream media outlets such as eNCA.

He is the host of the channel’s show So What Now?, which is about encouraging diversity in thought among left-wing and right-wing individuals, according to him. Last year, the BCCSA fined the show R10 000 for Covid-19 misinformation after Cliff’s guest, conspiracy theorist David Icke, claimed that it was a hoax in addition to other statements about the virus that were not scientifically backed. The Appeal Tribunal of the BCCSA later repealed the decision.

In everyone’s interest

William Bird of Media Monitoring Africa says the issue of regulation differs depending on whether journalistic entities – and people associated with those entities – create the podcast or whether non-journalistic entities and people are involved. “It’s in the credible media’s interest that existing regulatory codes are applied to podcasts so that the public has a sense of security.

“People know that they can report something … and that their complaint will be heard because there is some mechanism of accountability in place. This also speaks to giving the podcast some measure of credibility. At the moment, the only measure for that is the brand of the person or the entity … creating that podcast.”

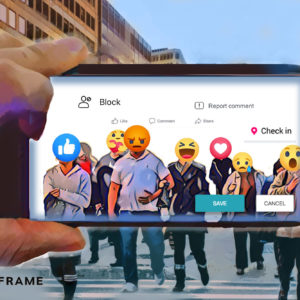

While a number of regulatory bodies hold journalists to account, non-journalistic entities, Bird suggests, can be monitored through co-regulatory and voluntary mechanisms, which he likens to those already in place on certain social media platforms. “We’re already talking about these mechanisms with Twitter and Facebook. If I put out misogynistic content and you feel it is unacceptable, you can report that to Facebook and they may decide to take the post down.”

Related article:

Bird highlights the current uncertainty about whether the podcasts are exempt from the list of publications the Film and Publications Board oversees. An amendment to the Film and Publications Act (1996) is slated for release soon, which could possibly address this ambiguity.

Candice Chirwa, menstruation activist and co-host of the podcast What The Relationship, describes the need to safeguard creative expression but not at the expense of those already vulnerable in our country. “As a podcaster, I believe that there is a bit of creativity that podcasters are meant to have when it comes to creating content. However, because the industry is not regulated, it allows problematic podcasters to have a free-for-all with their content.

“As a Black woman, I feel that podcasts that are hosted by heterosexual men who don’t want to have new ideas in their conversations but instead want to push a specific rhetoric can be dangerous. I think the onus is then on the podcast audience themselves to be mindful of the content they listen to and support.”

Related article:

Deplatforming – in which someone’s platform is either removed or highly impeded – is one way to deal with bigoted individuals with large public platforms. But it is often very difficult to do. Communities supporting the banned podcasts are unlikely to simply boycott the platform en masse, mostly because they have no issues with the kind of statements the host makes.

Tweet anything negative about MacG and you are almost guaranteed to be attacked by a follower (or seven) in return. Also, the outrage these hosts cause explodes and burns up exclusively online – in fact, a lot of the time podcasters use this as fuel for popularity, because the brouhaha almost always dissipates as quickly as it flares. So what does actual change look like outside digital media and our screens?

Inflammatory podcasts are on the rise and their notoriety will continue to lure in more listeners. As the podcasting space continues to grow in the country, we need to consider structures of accountability that rely neither on individual activism nor on regulatory bodies alone. One way or another, we need to step into this murky terrain for the benefit of those most vulnerable.