Camping on the doorstep of high school success

A principal in Umlazi has initiated profound changes to the way his school is run and its matrics are prepared for their all-important final exams amid trying circumstances at home.

Author:

16 November 2021

It’s Sunday morning 24 October and the temperature in Umlazi’s F Section, southwest of Durban, is 16°C. Rain falls intermittently. Dozens of matric pupils and their caregivers – mostly parents – have made their way to Embizweni High School to attend a presentation about the national senior certificate examinations, which begin in four days’ time.

Embizweni High School is a quintile two school, which means it’s a “no-fee school”, like all of those in quintiles one to three. In determining a school’s quintile ranking, the Department of Basic Education uses the income, literacy and unemployment levels in the community it serves as indices.

In the absence of an indoor assembly space at Embizweni, the caregivers sit huddled together in the cold outside a block of classrooms while the pupils, clad in their school uniforms, stand outside another one.

“There is nothing less than 90% of our parent and learner population in attendance,” principal Mondli Khubone, 57, says proudly. “Look at the weather, but they left their homes and came here. This is one of the things that pushes me, that we have the full support of the parents.”

The purpose of today’s meeting is multifold. First there are a few words of motivation by retired radio personality Eric Ngcobo, who is well known in Umlazi. Then the top performers in the recent trial examinations are revealed, after which a prayer is said for the matrics to succeed in their finals. Also on the agenda is the matter of the upcoming “matric camps”, which will see pupils stay over at school over weekends for the duration of the examination period.

Going for 100%

The camps are Khubone’s brainchild. He initiated them in 2019 when the matric pass rate was sitting at 57%. That year, the pass rate shot up to 76% and in 2020 it further increased to 86%. This was despite the effects of Covid-19 restrictions that seriously hampered schooling at Embizweni, with pupils unable to afford data for online learning.

This year, Khubone has his heart set on a 100% pass rate. To combat some of the challenges these matriculants faced when they were in grade 11 because of the restrictions, they attended school every Saturday as well as during holidays and on some Sundays this year.

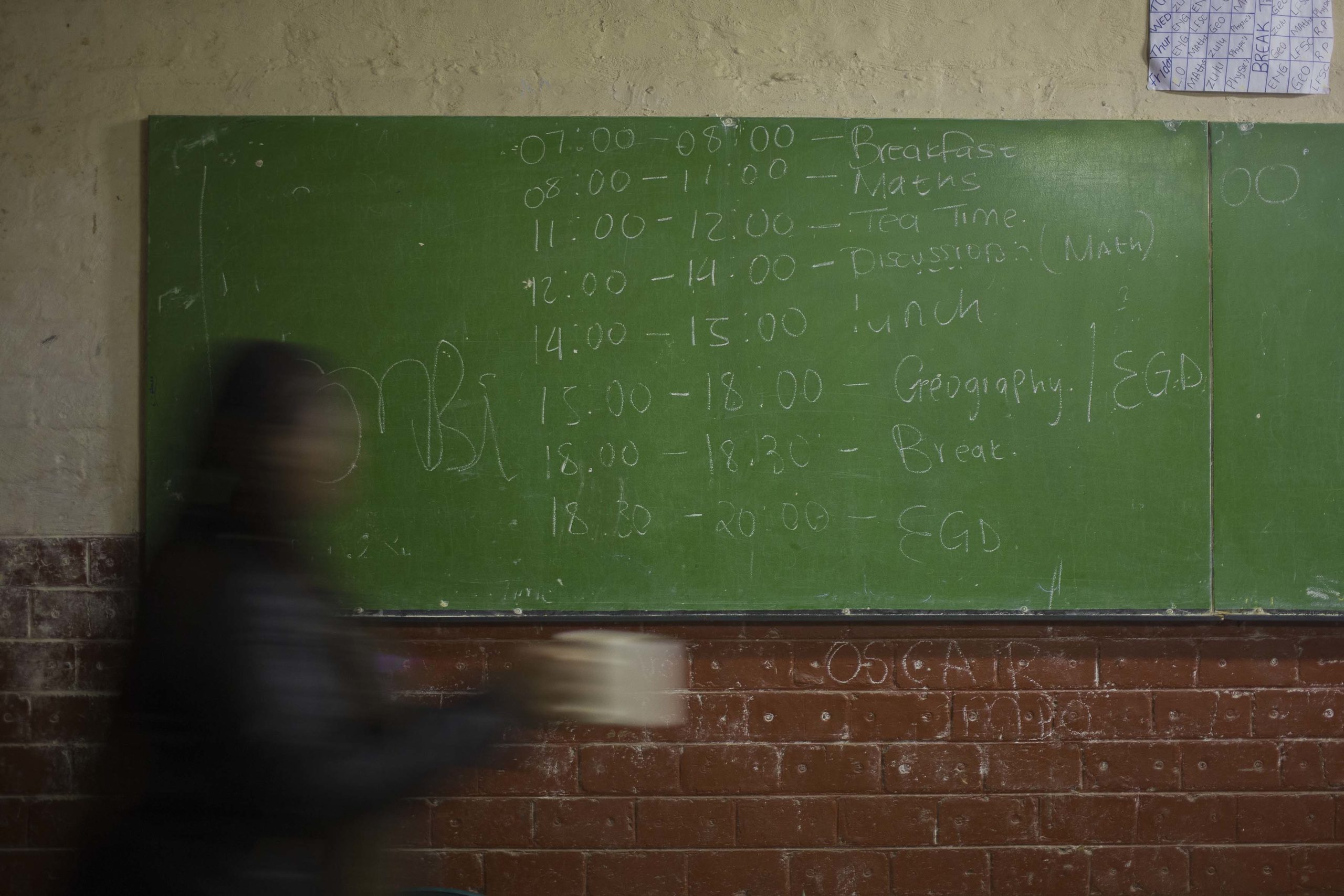

“The learners come to school on a Friday; they’ll leave on Monday evening at 6pm,” Khubone explains. “The idea is to keep them focused and away from all unnecessary troubles.”

The “troubles” he refers to are many and profound, and can make it impossible for the pupils to study at home. “These kids come from broken families,” Khubane says. “Sometimes their parents are getting drunk, sometimes there are taverns in their neighbourhoods. Sometimes the house they live in is too small for them to study in – you have the father, mother and children sleeping in one room. Some families can’t afford to pay for electricity. There are high rates of poverty in the area.”

Nomthandaso Kunene, 19, is attending the meeting with her aunt, Makhosi Shangase. Kunene shares a four-room RDP house with 10 relatives, including her aunt. Her father died in 2007 and her mother is unemployed. Her financial needs are taken care of by Shangase, who sells packets of potato crisps, fried chips, vetkoeks and ice cream from home.

Kunene, who placed 12th in the trial examinations, is aiming for five distinctions in the finals and wants to study sports science afterwards. She is looking forward to the camp because it is virtually impossible to study at home. “First of all there is noise at home, and secondly nobody is well-educated enough to help me with maths. I’m really struggling with maths,” she says.

“Mr Khubone is helping us obtain good marks with the camp. It’s so important for us to unite together as children to study, and to study hard to obtain good marks.”

Against the odds

Kunene is a good worker who is trying hard, says her aunt, but her circumstances at home make it difficult for her to study. “There are too many people. There’s too much noise and she isn’t able to concentrate. She’s a committed child, but the problem is she gets disturbed so much,” says Shangase.

“This camp is going to help them a lot. They’ll have enough time to study, and if they don’t understand something they’ll be able to ask their teachers.”

Nokwanda Khuzwayo, 18, also lives in an RDP house. Among the 11 people with whom she shares it are her ailing grandparents, who often summon her while she is studying. “They can’t get out of bed. They are sick [and] they call me to help them,” she says.

Khuzwayo’s mother, Nokulunga, adds: “If we use the lights, my parents complain. ‘Nokwanda, switch off the lights, we are sleeping,’ they say. It’s hard to study at home. It’s better for her to study at school. I’m very happy about the camp. Nobody will disturb her.”

Khuzwayo, who wants to go to university to study biomedical technology, agrees. “I’m very excited about the camp because I will be able to get help at school from teachers and other learners when there’s something I struggle with. Also, there will be no noise that will disturb me when I’m studying.”

Changing a culture

The camp is not the only thing that Khubone has brought to the school. When he arrived at Embizweni from the nearby Zwelibanzi High School in December 2016, he was in for a rude awakening.

“Zwelibanzi is a machine on every level: its discipline, its high-quality results. Recruiters used to come to us from the University of Cape Town and the University of the Free State,” Khubone says. “At Embizweni, there was ill discipline, there were pregnancies, there was late-coming, there were issues with learners wearing the incorrect uniform and coming to school with inappropriate hairstyles.”

Undeterred, Khubone rolled up his sleeves and got to work. He introduced afternoon lessons, which meant school finished at 4pm and not 2.45pm for grades 8 to 11, and at 6pm for matrics. Prior to the pandemic, the school also had a special programme called Siyayinqoba (We are defeating it) for older girls in grades 10 to 12. As part of the programme, staff from the local clinic spoke to them about teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, and motivated the girls to protect themselves against these. Leaders were chosen to relay the message to those in the lower grades.

Khubone also introduced daily morning assemblies and regular motivational talks by individuals from different walks of life. They would range from ex-prisoners and nurses to journalists and former students. The central theme in these sessions was how the speakers overcame their suffering to succeed.

But while the learning culture of the pupils has surely but slowly changed, Khubone faces another challenge: the absence of a strong teacher force. He points out that the school’s only physical science teacher retired in June and hasn’t been replaced owing to the department’s failure to act. A teacher from Pongola has been identified, but has not been approved by the department. Khubone also cites the example of a teacher who plays truant from lessons and sometimes shows up drunk. “Sometimes my children are very focused but they don’t have good educators,” he laments.

Khubone has gone the extra mile to work around this problem. “I put a full tank of petrol in my car and go very far. I go distances to look for teachers,” he says.

In the absence of a good mathematics teacher at Embizweni, he drove all the way to northern KwaZulu-Natal to acquire the services of Mthembeni Zulu, 36, a highly rated teacher who taught Khubone’s daughter at Umlazi Comprehensive Technical High School. “Mr Zulu is a different person altogether. He is very committed to his work. It doesn’t matter whether it’s day or night, as long as he’s assisting a child,” says Khubone.

“He [Khubone] told me he needed a special teacher for mathematics,” says Zulu, who is is not paid by the department and only earns R2 000 a month. Two other schools near Embizweni have since tried to lure him away with salaries of R15 000 and more a month but he turned down their offers. “It’s not about money. It’s for the sake of the learners and the community and loyalty to Mr Khubone, who brought me to Umlazi,” he says.

Promise in the air

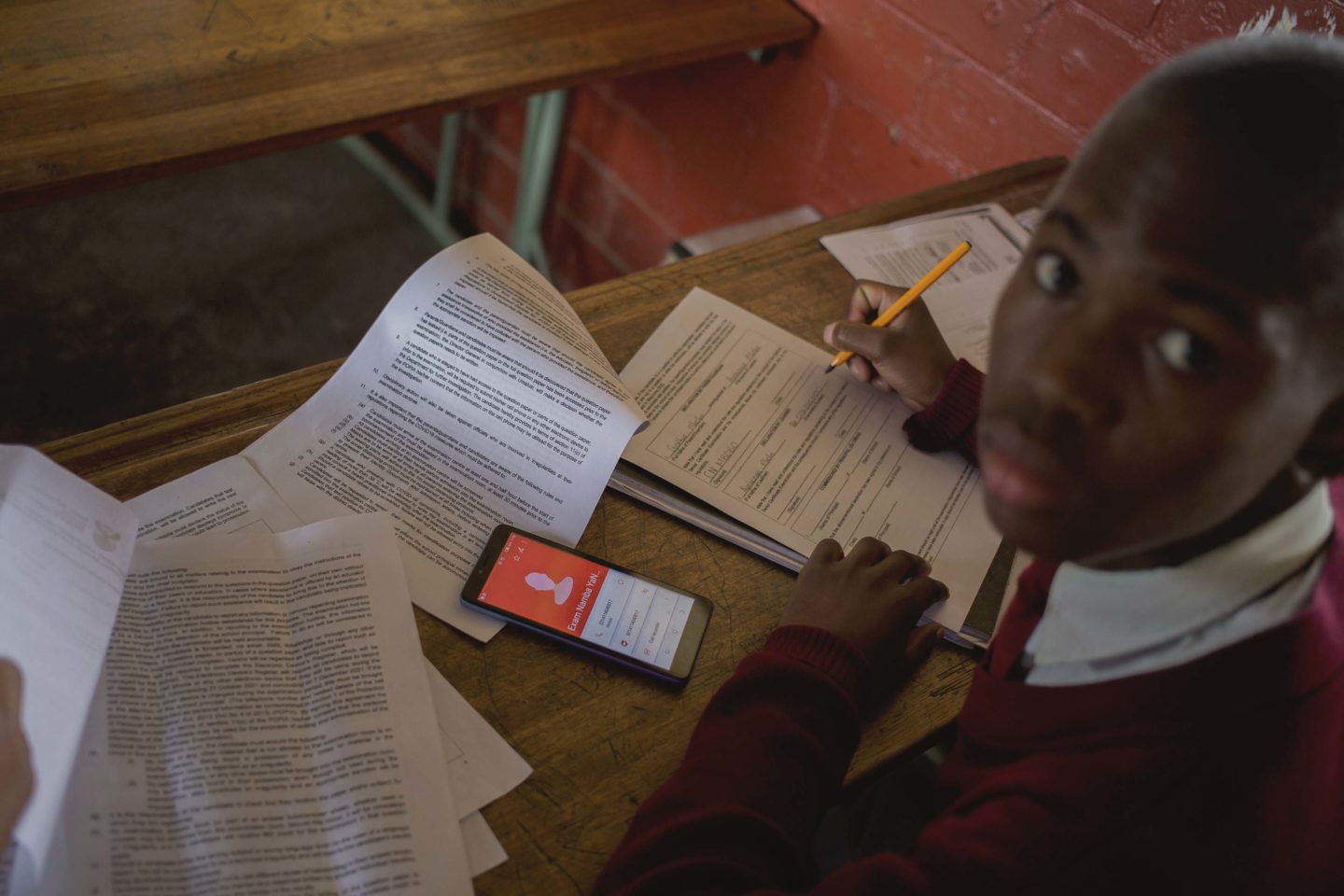

It’s Sunday evening 7 November and the matric camp is well under way at Embizweni. Tomorrow is a big day for the pupils, who will be writing mathematics paper 2 and mathematical literacy paper 2. Zulu is revising a mathematical concept on a chalkboard in one of the classrooms while outside, in the pouring rain, the other teachers are getting ready to serve dinner.

Zulu is full of praise for the camp. “It helps in terms of discipline and studying. They don’t have enough space to study at home,” he says. “I see a lot of commitment and dedication from the learners during the camp. While they are close to us, they are even asking questions; it’s an easy way for them to find teachers next to them.”

Alelisa Mzizi, 17, the president of the school learner representative council, says the camp has been splendid so far and enabled them to raise their achievement levels in mock exam papers. “Most of us were lacking in some subjects, but now that we are together as a family we have managed to move from level two to level four,” she says.

“It’s very difficult to study at home. Some of us are being abused, some of us are being influenced to do negative things by our friends … so being here at school is such a good thing because we are being protected from the outside world.”

Khubone is smiling from ear to ear. “The camp has been very successful so far,” he says. “We have 168 learners writing the examinations and only one child is not here because he had a problem at home. It’s not easy to achieve 100% attendance even during normal school hours, let alone coming to sleep at school. This shows me that the parents trust me, otherwise they won’t send their children.

“I am hoping the camp will move us from an 86% pass rate to 100% pass rate,” Khubone continues. “That is my wish. If I look at the behaviour of the learners and the preparation, I’d say we are still very much on track towards achieving that.”

Fatima Asmal belongs to the Institute for Learning and Motivation – South Africa, a non-governmental organisation that supplies meals for the weekend camps.