CA Davids, a quiet revolutionary

In both her novels, the South African author asks how people and nations can become accountable, mapping complex narrative threads that span the globe and probe the heart.

Author:

4 May 2022

There is a small scene in CA Davids’ debut novel, The Blacks of Cape Town, that passes by almost unnoticed.

In it, protagonist Zara Black is mute and unresponsive at her mother Lena’s funeral. Watching mourners go by, she pays few mind, until one of Lena’s former students stops to offer his condolences. Zara looks up when he remarks that Lena was a true revolutionary, remembering her mother quite differently to her. Zara asks him what he means by this and the mourner replies, “She always asked that we think and question everything, to never take the easiest way out, even if it is convenient. She asked for something more from us.”

A few years later Zara recognises his face in a newspaper report on an investigation into his death after whistle-blowing on his employer for building flimsy houses that collapsed on their sleeping inhabitants during the first winter storm. Zara recalls his sincere tribute to her mother and marvels at how, in his own way, he too turned out to be “a quiet revolutionary”. This subtle moment speaks volumes about both the writer and her novels.

Related article:

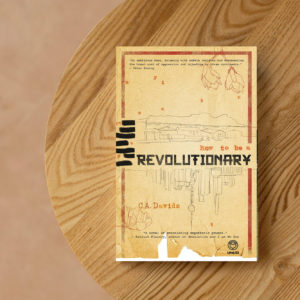

As a writer, Davids asks more of herself. Her recently published second novel, How To Be a Revolutionary, is testament to both her commitment to her craft and her perseverance in the face of an unforgiving South African publishing industry. At the book’s launch at the Book Lounge in Cape Town, Davids explained that “compared to getting it published, writing the novel was the easy part.” That said, the novel went through at least 15 revisions during the five years that she tried to get it published.

Writer Bongani Kona describes Davids’ talent as glimmering in The Blacks of Cape Town but fully on display in How To Be a Revolutionary, a novel that “asks us to pay attention to the stories we tell about the past; not only to what we remember but how we remember”.

As a person, Davids asks more of the world, too. Both novels are interventions in accountability, probing how individuals and societies justify their actions, not just in terms of taking responsibility for historic wrongs, but also to strive for future success.

How to be accountable

The Blacks of Cape Town connects the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley with the election of Barack Obama through Zara, a South African historian at a university in the United States trying to make sense of herself, her origins and a family history of betrayal. Similarly, How To Be a Revolutionary also straddles continents, this time following Beth, an anti-apartheid student activist who ends up working in the government, accepting a diplomatic post in Shanghai to flee her unhappy marriage in Cape Town. The novel links Beth’s historic and new friendships in South Africa and China, their accompanying intrigues, and the demands that arise when personal life and public duty overlap.

As we talk over Zoom, Davids describes the two novels as the work of her adult life, her interiority, and how she processes politics globally and in South Africa. Producing creative work focused on questions of accounting for yourself, others and the world at large runs the risk of coming across as preachy, but there is an earnestness to Davids’ efforts that saves her. This could be because of her enduring Star Trek fandom, which she describes as an influence during apartheid because of how the series focused on “our higher selves as human beings”. It also might explain the fast-paced engine of both plots.

How To Be a Revolutionary, for instance, brilliantly weaves numerous narrative strands: present-day Beth navigating modern-day China; Beth in the 1980s as a schoolgirl during apartheid; her new friend Zhao, a journalist during the Tiananmen Square uprising; his research into the 1950s famine years of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward; and his memories of the student massacre in 1989. Remarkably, Davids also creates space for a third character’s voice: an imaginary Langston Hughes.

Related article:

In a recent article for LitHub, Davids describes how the American poet entered the fold as a result of her research to solve a technical problem while writing the novel. She came across an article about Hughes’ visit to Shanghai during the 1930s and a rare copy of Langston Hughes and the South African Drum Generation: The Correspondence, a collection of letters exchanged between the poet and several South African writers.

In her novel, Davids imagines Hughes writing from China and Harlem in the 1950s, and centres his commitment to supporting African writers by fictionalising the real-life exchange “that today seems extraordinary: collaboration and a transatlantic exchange of ideas that Hughes found personally and intellectually fulfilling”.

Davids treats Hughes as more than just a technical solution or a famous guest appearance. She is as careful with the “many silences – especially around his sexuality and political beliefs” that continue to characterise the poet as she is of addressing the unspoken rules of Chinese culture, such as the notion of “face saving” – pretending not to see an indiscretion to allow the other person to avoid embarrassment.

Related article:

For Davids, “caution is not only necessary but perhaps a fundamental act of empathy”, evident in how she crafts and navigates both characters and contexts. Her characters are full and fallible, their settings rigorously researched and believable. Both are important given the emotionally delicate and politically charged subject matter of her novels.

One character in The Blacks of Cape Town says: “Our country’s a museum of loss, our killing fields aren’t filled with corpses, even if the bodies are there. No, our museum is populated with betrayals, stacked sky high.” Davids writes as if she knows this to be true of all countries. Much like Zara, “she understands history in a way that one could only understand a great love: with acceptance, patience and forgiveness”.

Davids works prudently with archival material and current affairs to engage with how individual and collective memory can be at once a lament of the status quo and a call to arms to change it. Perhaps this is the crux of accountability: recognising things for what they are but striving to improve them.

On conviction, complicity and hope

Like Mr Spock, her work reveals an acute awareness that “change is the essential process of all existence”. In an essay for Wasafriri magazine, Davids writes about patterns of pandemic time and of injustice in South Africa, how “hope is intertwined with change” and how “change will require something from us all, some more than others”.

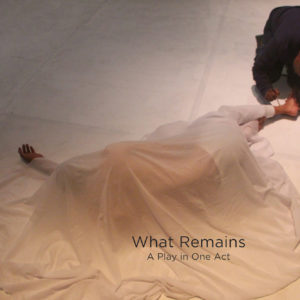

At the launch, Davids described her own difficulty in living with complete conviction, whether it be grappling with the tension between national and personal identity or the stress of feeling complicit in issues of intergenerational justice, like redress for political crimes or the climate crisis. But in facing this difficulty with determination, through the medium of her novels, she too exhibits “an essence, a rebellious being, a warrior spirit” described by Beth in How To Be a Revolutionary, choosing fiction to forensically interrogate notions of activism, belonging and change.