Book review | The tragedy of the worker

A radical collective committed to change in the face of climate collapse calls for global solidarity and a turn to the worker to revolutionise how we relate to the world.

Author:

5 October 2021

The tone of The Tragedy of the Worker: Towards the Proletarocene is set in the opening paragraph with a sobering addendum to the Communist Manifesto’s most well-known sentences: “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win. What if the world is already lost?”

This important new book, written by the Salvage Collective – of which well-known science fiction author China Miéville is a member – is a manifesto-like cry to countenance the state of our social and ecological lifeworlds, and to grapple with the question of how “we imagine emancipation on an at best partially habitable planet”. Herein, for Salvage, lies the titular concern of the book, which unashamedly wears its politics on its sleeve: the tragedy of the worker is that “she was put to work for the accumulation of capital, from capitalism’s youth, amid means of production not of her choosing, and with a telos of ecological catastrophe”.

Related article:

How do we think about progressive – even revolutionary – forms of politics when we live “at a point of history where the full horror of the methods of fossil capitalism is becoming clear”, and where, even if capitalism were overthrown tomorrow, we would “inherit productive forces inextricable from mass, trans-species death”?

As we are relentlessly reminded throughout the text, the situation is not good. The current confluence of accelerating ecological crises, most popularly termed the “Anthropocene” or the “sixth mass extinction crisis” is, as Salvage describes, “a megaphase change taking place in microphase time”.

Without illusions

While this change is something with which we are all viscerally familiar, being reminded daily in the media, not to mention by the increasing instability of the weather itself, the crisis has also become what philosopher Timothy Morton terms a “hyperobject” – something too vast and complex for us to fathom.

Given our fundamental inability to properly face the ecological whirlwind and the deep existential threat it poses to all human life, it is entirely unsurprising that so many of us have averted our gaze to other more immediate issues. We find ourselves quickly scrolling past the myriad articles on wildfires, species extinction, acidifying oceans, coral reef bleaching, insect biomass collapses and climate refugees fleeing encroaching famine in hot, faraway countries, and ignoring the fact that rain and sunshine, heatwave and snowstorm, are increasingly at odds with the seasons. We have 60 harvests left.

Related article:

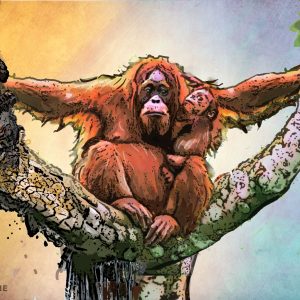

The authors would prefer us to face the problem head-on, without illusions. To acknowledge the fate of “narwhals, polar bears, beluga whales, the Pacific walrus, peregrine falcons, ringed seals, spoonbill sandpipers, golden plovers, kittiwakes, and black guillemots”, and to mourn the disappearance of “design after exquisite designless design, evolutionary one-offs, anatomical glories, once gone never to be seen again, edging closer to the furnace of global heating”. To traverse the “dead zones” where wild ecosystems are converted into ghostly monocultures.

Salvage describe their position as self-falsifying pessimism: an eminently realistic refusal to sugar-coat the stark realities of the 21st century, and one evidently imbued with a lived knowledge of the dangers of the mandatory optimism of progressive politics. The key is in the term “self-falsifying” – this is a politics that draws hope and hopelessness, hubris and humility, into a productive tension, seeking a rupture with the rapacity of capitalism at the same time as it acknowledges the damage done and to come. The authors invite us to view revolution not as the seizing of the means of production of ecocide, but instead as the only viable form of mitigation and adaptation to our new ecological context. Employing a Marxist register, they underscore this point by inviting us to view the new mode of production we so desperately require as a complete transformation of “our ways of making, thinking, eating, moving and living”.

Beyond capitalism

That this new mode is to be sought beyond capitalism is underpinned by the authors’ convictions that beneath the various cycles of carbon, species migration, topsoil renewal, rainforest growth and so forth that form the subject matter of environmental discourse, there is a fundamental circuit of capital accumulation that “subsumes these life processes, these flows of energy, these microbial dependencies, within its own molecular flow” and “subordinates them to the homogenising frame of value-production”. This is “a regime of creative-destructive accumulation that is as inexhaustible as biospheric resources are finite”.

Given what they describe as the infinite drive of capitalist expansion to metabolise both the natural world and the labour of the broad masses of humanity, it would seem that “the only terminal limit to capital’s perpetual augmentation is, if driven towards from within, external: either revolution or human extinction; communism, or the common ruin of the contending classes”.

Related article:

Hyperbolic though this may appear at first glance, it reflects a hard-won pragmatism, borne out in the nuanced critical engagement with various doomed responses to the ecological crisis that forms the bulk of the text. Salvage take us through these responses one by one, exploring their oftentimes myopic or disingenuous underpinnings, as well as their limitations.

Of these responses, denial, once the most popular form of market liberal reaction to climate change, has become, in the post-Kyoto age, unpalatable to all but the most inveterate right-wingers. Donald Trump may still be describing fossil fuels as “molecules of freedom” while the far-right Alternative für Deutschland rages against Greta Thunberg, describing her as part of a sophisticated “PR hoax”, but bastions of petromodernity such as BP and ExxonMobil have long since signed on to the Paris Accords and rebranded themselves as seeking to move “Beyond Petroleum”.

Unproductive and harmful approaches

This is not to ignore the alarming growth of right-wing phenomena like ecofascism, which, as Salvage put it, fuses “the connectedness of all matter, biotic and abiotic … with romantic nationalism”. The increasingly common intersection of fascism and environmentalism should not surprise us: the term “ecology” was most likely coined by Ernst Haeckel, a German zoologist whose political views combined “eco-holism, racist social Darwinism and volkishness”, and the term “holism” comes from Jan Smuts. Historically, the authors remind us, racism and environmentalism made comfortable bedfellows, and “the far right treated racist murder as biological conservation and segregation as good husbandry”.

This ethos of “ecological holism” is reflected, albeit in much milder form, in the parochial hankering for “the good old ways” among a certain section of the contemporary green movement, as well as in a significant amount of conservationist ideology. And, as the Narendra Modi government’s response to the 2018 Kerala floods, which has been described as “disaster fascism”, makes clear, it intersects with populism, nationalism and caste hierarchies in deeply troubling ways. Some Modi supporters even went so far as claiming that the floods were Kerala’s punishment for being too communist.

Related article:

While the resurgence of fascism and other forms of far-right reaction remains a dire political problem, Salvage view mainstream liberal and progressive approaches to the ecological crisis as at least equally problematic. These approaches are clustered under the provocative term “disaster centrism”, which offers a series of variations on attempting to solve problems via the same logic that causes them. Describing it as a form of “implicatory denial”, the authors are unrelenting in their criticism of this disavowal which, despite both growing evidence and simple common sense, continues to view measures like carbon credit trading and the vague, symbolic hand waving of Kyoto and Paris as necessary and sufficient interventions.

Capitalism’s accommodations and adaptations

Capitalism, Salvage observes, easily accommodates both denial and its disaster centrism variant, “denial-denial”, which acknowledges the scale of the crisis while simultaneously calling for a business-as-usual approach bound to perpetuate it. This is evident in the numerous green capitalist solutions that have been touted in recent years.

While shifting to mixed renewable energy sources and seeking out more efficient forms of habitation, transport, communications technologies, food production and so forth are crucial, pursuing this goal within a capitalist framework has mostly served to open up “a profitable niche of capital accumulation, with minor energy-saving and ‘clean’ technologies being sold as world-saving innovations”. In doing so, they fall prey to the Jevons Paradox, which states that as efficiency increases in the use of any particular natural resource, total demand does not decrease, but in fact tends to stay the same or even increase. This may seem counterintuitive, but if you have a hundred barrels of oil to sell and your major buyers are reducing their purchases, you are going to find extra uses and more buyers.

Similarly, efficiency does not minimise waste. As the authors bluntly put it, to think that “‘more efficient’ capitalism would ‘solve the problem’ of ‘the environment’ would be to fail to understand waste, capitalism and ecology: that the first is intrinsic to the second; that the second, whatever the degree to which it is inflected by the first, is inimical to the third”.

Related article:

Somewhere between ecofascism and green capitalist adaptation lies the “Green Zone-style survivalism of the rich” – an acquiescence to the ecological consequences of capitalism that focuses on entirely reactive measures like bunker building and elitist space migration fantasies. While on one level this represents little more than the vanities of billionaires, wider forms of reactive adaptation are also the focus of national security in wealthy countries. “Natural security” is a key goal of institutions like the Pentagon, and combines the very worst forms of militarisation and border control with US paternalism and dystopian “climate-change management” strategies.

Even within progressive circles, a reactionary form of adaptation is becoming increasingly common, as exemplified by the collapsist-catastrophist rhetoric of Extinction Rebellion’s Deep Adaptation community and the United Kingdom’s Dark Mountain Project. On the other hand, Extinction Rebellion has created a welcome groundswell of grassroots resistance to climate change with its tactics of consciousness-raising and civil disobedience, but the project remains hamstrung by its egregious political naïveté, positioning itself as “beyond politics” while it continues to reproduce liberal democratic tropes and endorse market solutions and authoritarian state intervention as viable strategies. As Salvage adeptly observe, “To rely on moral suasion alone – indeed to treat capital and the state allies in a programme ‘beyond politics’ that nonetheless amounts to a complete rupture with the present – is to try and make a social revolution without enemies.”

Turning to the workers’ movement

Finally, even on the Left, it remains the case that the workers’ movement has only episodically been able to recognise that “resistance to fossil capital is class self-defence”. More often, including in “Pink Tide” countries like Bolivia and Venezuela, an extractivist apologism that downplays ecological issues and appeals to pressing economic exigencies ties workers’ hopes “to the energetic foundations of capitalism and its apparent proffer of liberation from back-breaking labour”.

A frequent response to this criticism of the reliance of socialist regimes on fossil fuels, mining and other extractive industries is to invoke the “shopworn cliché according to which environmental consciousness is incorrigibly bourgeois”. But, as the authors show, working-class environmentalism in fact predates the origins of its better-known middle-class cousin, which is popularly believed to have emerged fully formed upon the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal Silent Spring. From mineworkers against strip mining to union battles for clean air and water legislation, workers, whose communities usually bear the brunt of the ecological externalities of production, were instrumental in the growth of environmentalism.

Related article:

“Whatever else they have been,” Salvage remind us, “struggles over waste in Naples, toxic dumping in Love Canal or the Bhopal disaster, have been class struggles waged by the poor”, a fact that is obvious to grassroots movements like Mexico’s Zapatistas and Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement, for whom social and ecological justice are entirely inextricable from each other.

Calling for global solidarity

Towards the end of the book, the authors, describing the “phantom limb” of old-school forms of socialism, call on the Left to “register its own illusions, its own hubris, its own defeats” and, in a plea for global solidarity across lines of class, race and national belonging, to acknowledge that we are, all of us, “bearers of a common, if unevenly distributed, guilt” and “a shared if unequal fate”.

In building this solidarity, we should not look to noble redeemers. It has become increasingly common for environmental activists to fetishise indigenous cosmologies and forms of life as sources of resilience, or, as Salvage put it, as “a form of world-historical mindfulness training, with which to face the disaster”. However, “capitalogenic climate breakdown is a real abstraction, not an ethical choice or epistemological preference”, and “the only way is through, not out”.

Related article:

In the final paragraphs, we may, quite reasonably, expect the authors to outline a programme of action, given their stinging dismissal of almost all forms of environmental activism. Detailed answers, however, are not the focus of this book, and the authors refuse, like Karl Marx, to “write the cookbooks of the future”. Indeed, to expect a 72-page book to exhaustively define “a transformation of a scale scarcely imaginable from this low vantage point”, which entails “a revolution in how we metabolise the planet, how we relate to all matter, what we eat, how we travel, what we think is good, what we think is pleasurable” – “a complete and irreversible transvaluation of values”, is wildly unrealistic.

We should, of course, “formulate a version of plenty, of abundance, that does not brazenly override ecological limitations”, and there is nothing wrong with indulging in restrained collective speculation as to the composition of the world we would like to inherit. Certainly, “all politics must become disaster politics”, but for the most part, we need to accept that we are “learning to walk again, pain in that phantom limb and all”, and heed Ursula K Le Guin’s wisdom in The Left Hand of Darkness: “To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needful in times of stress and darkness.”