Body of bodies: Art as a language of history

With his first solo exhibition, Kaelo Molefe transforms his trauma by merging his experience of being an emergency room doctor with art critical of the history of medicine.

Author:

18 October 2021

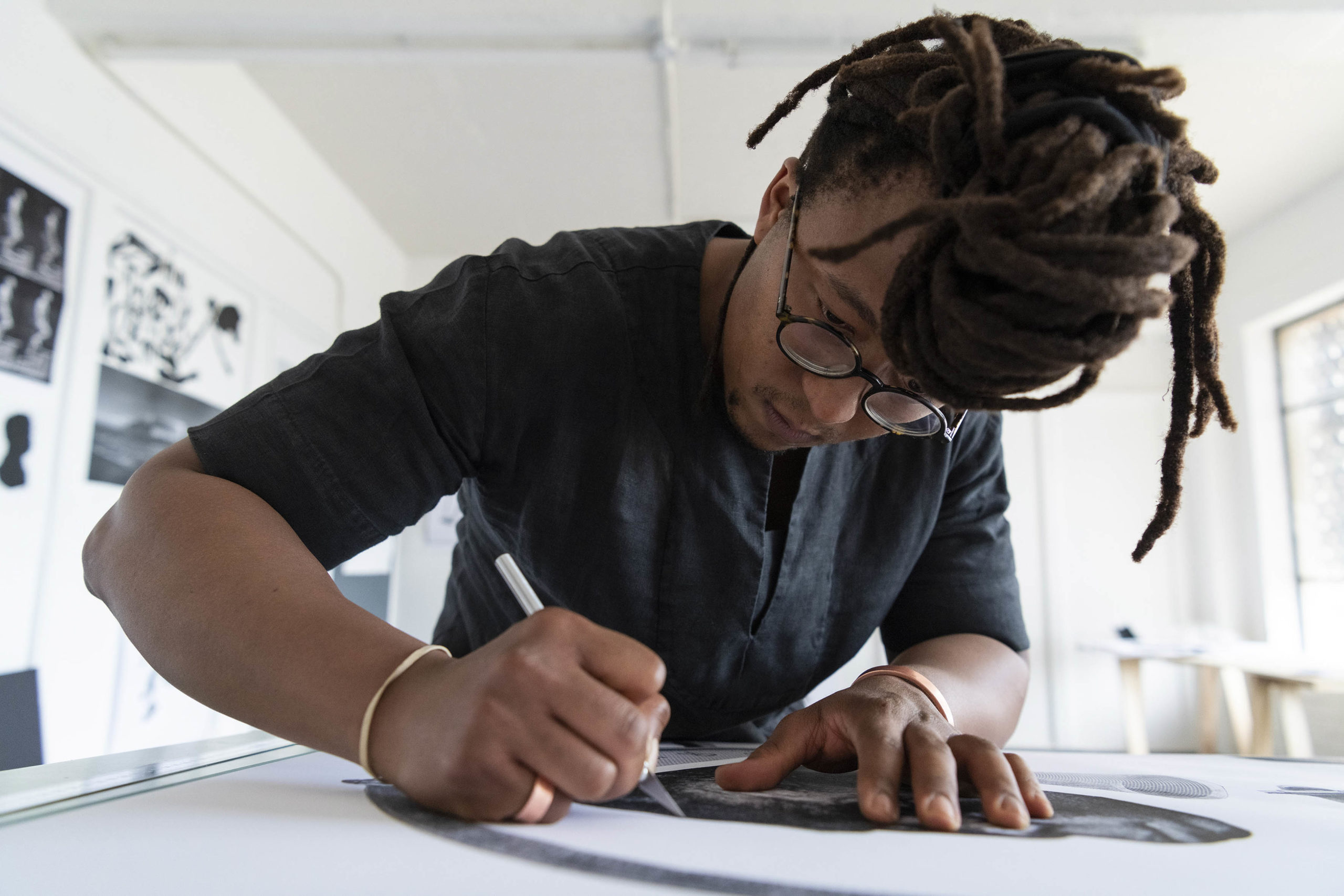

Visual artist and medical doctor Kaelo Molefe’s waist-length locks form a loose knot at the top of his head. He started growing his hair in 2009 as a way of marking time while studying medicine at the University of Cape Town. Similarly, his art is an intense study of time.

Molefe’s In The Midst of Other Objects: Schematics for the (Re)Construction of the Complete Gentleman in the Marketplace comprises 12 black and white collages exhibited at the experimental pop-up gallery 1004 in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. The exhibition space is a Hillbrow apartment owned by partners and independent gallerists Amie Soudien and Daniel Gray.

Molefe’s first solo exhibition is an artistic practice of historiography. It is partly about the sciences historically deployed to control and oppress, as seen retrospectively by him, and partly an artistic expression of his daily life as a doctor. Sweeping through South Africa’s history thematically but not chronologically, each sparse collage work is what the artist calls a “schematic”. They are made up of cut-out images from anatomical textbooks, colonial and apartheid-era anthropological photographic archives, and image archives of South African Black people.

Molefe is critical of the history of medical practice. The central work, The Cephalic Index, shows the stand for a would-be globe of the Earth, but part of a Black man’s face, a section of a clock and a loudhailer replace the spherical map. The title references a pseudo-scientific system popularised in the late 19th century for racially categorising and discriminating against people according to the dimensions of their heads. His work points out biomedical and biological racist practices that were once accepted and widely practised. The cranium is a theme across the exhibition.

The second part of the exhibition’s title, Schematics for the (Re)Construction of the Complete Gentleman in the Marketplace, references novelist Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard. In the novel, an unnamed man’s insatiable appetite for palm wine prompts him to embark on a quest to locate his expert palm wine tapper after his sudden death, and bring him back. In the process, the “father of gods who could do anything in this world” – as he names himself – encounters a man who attends a local market and looks the image of a near-perfect gentleman. But when this gentleman leaves the market, he passes a number of houses where he removes and returns body parts he has rented. Upon returning home, he is only a skull.

By using The Palm-Wine Drinkard in his work, Molefe questions how the marketplace has historically reduced and essentialised Black people to measurable features used as a basis for discrimination and oppression.

Complex, conjoined practices

Molefe’s relationship with medicine is complex. “I work in medicine to make money to make art,” he says. Between making art at his studio in central Johannesburg, he is a doctor in the emergency room of the Far East Rand Hospital in Springs.

“In my family,” Moelefe says, “there are quite a number of doctors. There was one uncle who was very influential. He was a very intelligent and charismatic person. From childhood, I looked up to him. In my naïve mind, I [thought] I want to be like him so I must be a doctor.”

Recalling his time in medical school, he says: “It was hard, I’m not going to lie. I was never diagnosed clinically, but I was very sad for a lot of that time. Because I was doing it out of necessity rather than out of love for many years, I didn’t do as well as I could have.”

Today, medicine blends with art. “Medicine has influenced the way I look, the way I see and the way I think. I remember being an intern at Joburg Gen [now Charlotte Maxeke hospital] in the trauma section. Ninety-five percent of the patients were young Black men. Some of them were burnt with their skin completely off. Some of them [had] an arm hanging off. Some of them [were] stabbed.”

After some time working at the hospital, he thought that “these guys look like me. What effect is this having on how I see Black men and Black bodies? Those things are starting to show up in the work in ways I didn’t realise … Trying to make sense of … trauma is playing out in the work.”

From practice to page

In making these works, Molefe wanted to develop an artistic language that could articulate the injury and illness he saw as part of his practising medicine. He also wanted a way to channel the trauma he was experiencing in the hospital.

“At Far East Rand, the place where I work now, there was a guy who came in … he had stolen some copper wires and there was a huge electrical explosion and he was burnt all over his body. He was meant to be admitted to the hospital but he refused. He came back the following week and the burns were so infected [that] when we undressed him, there were maggots pouring out of his body. The infection had gone so deep that the bone was exposed. The only time I had seen a body like that was in a morgue. That image of a broken body, still alive, traumatised me.

Related article:

“I remember driving home after that shift and crying. And then sleeping and being haunted by that image … I didn’t realise how much I was trying to gain control over those images instead of them swimming in my mind, coming to me without me being able to control them. Maybe if I can put them on a page, I [could] make sense of them in some way.”

In showing these works, Molefe is not only gaining control of his memory and drawing lines between historical themes, he is also getting another perspective on his trauma as viewers take in the work. “Now that I’m showing my work,” Molefe says, “other people are helping me to see it better. It’s a kind of reckoning.”

Making meaning from experience

The first section of the exhibition’s title, In The Midst of Other Objects, references a moment in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks where the psychiatrist and philosopher feels himself reduced to an object, as opposed to a person who might fulfil “the desire to attain to the source of the world”.

When people look at Molefe’s artworks, they give credence to his personhood and pain and thus make it more real. They also give the artworks deeper meaning for the artist. “Sealed into that crushing objecthood,” Fanon writes, “I turned beseechingly to others. Their attention was a liberation, running over my body suddenly abraded into nonbeing, endowing me once more with an agility that I had thought lost, and by taking me out of the world, restoring me to it.”

But there is a danger here, as Fanon experienced, that this desire to show might trap Molefe in a particular state. “But just as I reached the other side,” Fanon continues, “I stumbled, and the movements, the attitudes, the glances of the other fixed me there, in the sense in which a chemical solution is fixed by a dye. I was indignant; I demanded an explanation. Nothing happened. I burst apart. Now the fragments have been put together again by another self.”

The viewer gains from Molefe’s ability to draw parallels and thematic relations between what has happened before and how this affects the present. But for the early-career artist still solidifying his style and voice, the ties that bind his works into a single practice might appear tenuous. The viewer needs to have knowledge of Molefe’s lived experience of dealing daily with the outcomes of an oppressive and violent history to make the necessary connections in the work.

Molefe initially tried using medical scalpels to make his art, but he soon realised that “flesh is much softer than paper” – a profound vulnerability. At 31 years old, he is experiencing a transformative period with his first solo exhibition. The show reaches beyond historical incidence into the process of making meaning from experience. It eschews simplistic therapy and draws parallels between the fragility of flesh and how lives are lived and remembered, even in their final moments.