Black women artists in a monumental exhibition

Spanning six decades and featuring more than 150 Black South African women, this art curation is an important intervention between the artists and the archive.

Author:

21 June 2022

The exhibition When Rain Clouds Gather: Black South African Women Artists, 1940-2000 is, in multiple ways, monumental. To be monumental is to first bear testimony to importance across time, an allusion to memory and archive. Second, monuments take up space by rising above what else is visible, sometimes imposing, always formidable. Third, they make demands on our imagination and generate ways of thinking about significance.

The sheer scale of the exhibition is breathtaking: it shows the work of more than 150 painters, sculptors, printmakers, etchers, photographers, weavers, ceramic artists and embroiderers alongside each other, presented as intellectuals connected in a rich tapestry of Black women’s artwork across six decades.

The curatorial choices and gestures of Portia Malatjie and Nontobeko Ntombela create an exhibition that stands as a monument: making an important curatorial and art historical intervention into the relationships between Black women artists and the archive, canon-formation and imagination.

On show at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town until January 2023, the exhibition is named after Bessie Head’s 1968 novel When Rain Clouds Gather, which charts a hopeful vision crafted through strife and turmoil.

In Head’s novel, Makhaya, a South African anti-apartheid activist, must come to terms with what it means to make a home in his chosen homeland, Botswana. He expresses this desire: “I want to feel what it is like to live in a free country and then maybe some of the evils in my life will correct themselves.” Failing to find deliverance in Botswana, he must discover that such a home has to be imagined, and built with other undesirables, in the fictional village, Golema Mmidi, whose name translates as “to grow corn”.

As experienced curators and teachers of art at the Universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand respectively, Malatjie and Ntombela are alert to the fact that Black South African women’s art-making is an encumbered terrain. They know that navigating through it demands attention to what has been amplified, obscured and diminished by institutionalised choices in the academic and art worlds.

In response, the curators choose to surface multiple trajectories, visual vocabularies and thematic preoccupations of Black women artists across six decades. And in doing so, they expand understandings of the place, scale, sites and visual languages of Black women’s creativity.

A statement of intent

At the exhibition’s entrance, a large curatorial statement is flanked by incomplete lists of Black South African women artists included and left out of this exhibition. This is the dance of presence and occlusion, of possibility and irretrievable loss at the heart of the show. Yet abundance hugs the deep green and navy walls of Malatjie and Ntombela’s maze-like exhibition, and rises from the floor spaces.

This first room is a statement of intent. It foregrounds the importance of context in thinking about, and thinking with, the Black women artists exhibited. It is also a reminder that the exhibition does not enter a vacant space by pointing to the worlds that produce these women artists and the worlds of ideas to which they speak. In display cabinets, a timeline on the wall, book and album cover images, the curators link their chosen artists with historical developments in South Africa and to their Black women creative peers in music, literature, politics and popular culture.

In refusing the dominant reading of Black women artists as either exceptional or marginal, Malatjie and Ntombela both gesture to infinitely more sophisticated contexts for the works on display, and as well as for making sense of the creative production of their exhibition.

What important insights emerge when we read these artworks as part of larger engagements with the times, societies and imaginative practices of their eras?

As art historians, the curators know that anthropological or sociological readings are offered to Black women artists in place of art criticism, that some genres are taken for granted as art while others are easier to dismiss.

This is true whether one contrasts an established art form such as painting with an arriviste such as photography, or the pretence that “art” is always clearly distinguishable from “craft”. They recognise that the cumbersome label “craft” as used to dismiss many sites of creativity by Black women is a historically inflected expression of power, not the simple matter of discernment it is often paraded as. They know too that to debate this ad nauseam sidesteps the critical neglect of substantial bodies of work in taken-for-granted artforms produced by Black women.

In When Rain Clouds Gather, the boundaries of form, categorisation, reading or curatorial praxis are themselves subject to scrutiny.

Leaving this first room, choices abound.

So much possibility

The exhibition is arranged like a maze. This maps out a multidirectional archive of Black women artists, a recognition which the viewer is obliged to confirm. Choices are made about which direction to turn, which order to follow. Rooms spill into the long passage from both sides.

It is impossible to ignore the short wall texts printed at the entrance of each room. Their placement acts as a guide to the thinking of the curators, yet they resist explaining the rooms into which they open. Although they take on the shape of statements, they are an invitation to question how meaning is made by these artworks.

In a move that is as playful as it is powerful, these statements are not of the same kind. The heading “Political” does not tell us the same kind of information as the title “Esther Mahlangu” or “Wrestling Traumas” or even “Love|Pleasure|Intimacy”. Each is a different battle with categorisation, and one that allows us to think as much about the classifications as across them. They offer what Gabeba Baderoon might call “a leaking of meanings”, or insert us into what the curators call “itinerant archives”. An itinerant archive is a conceptually mobile one. Along the passage, Diana Mabunda’s Twenty Rings from 2000 takes up an entire wall. The rings, on loan from the Durban Art Gallery collection, are beaded embroidery on velvet. At the end of the same corridor an imposing Mahlangu photograph and BMW beckon.

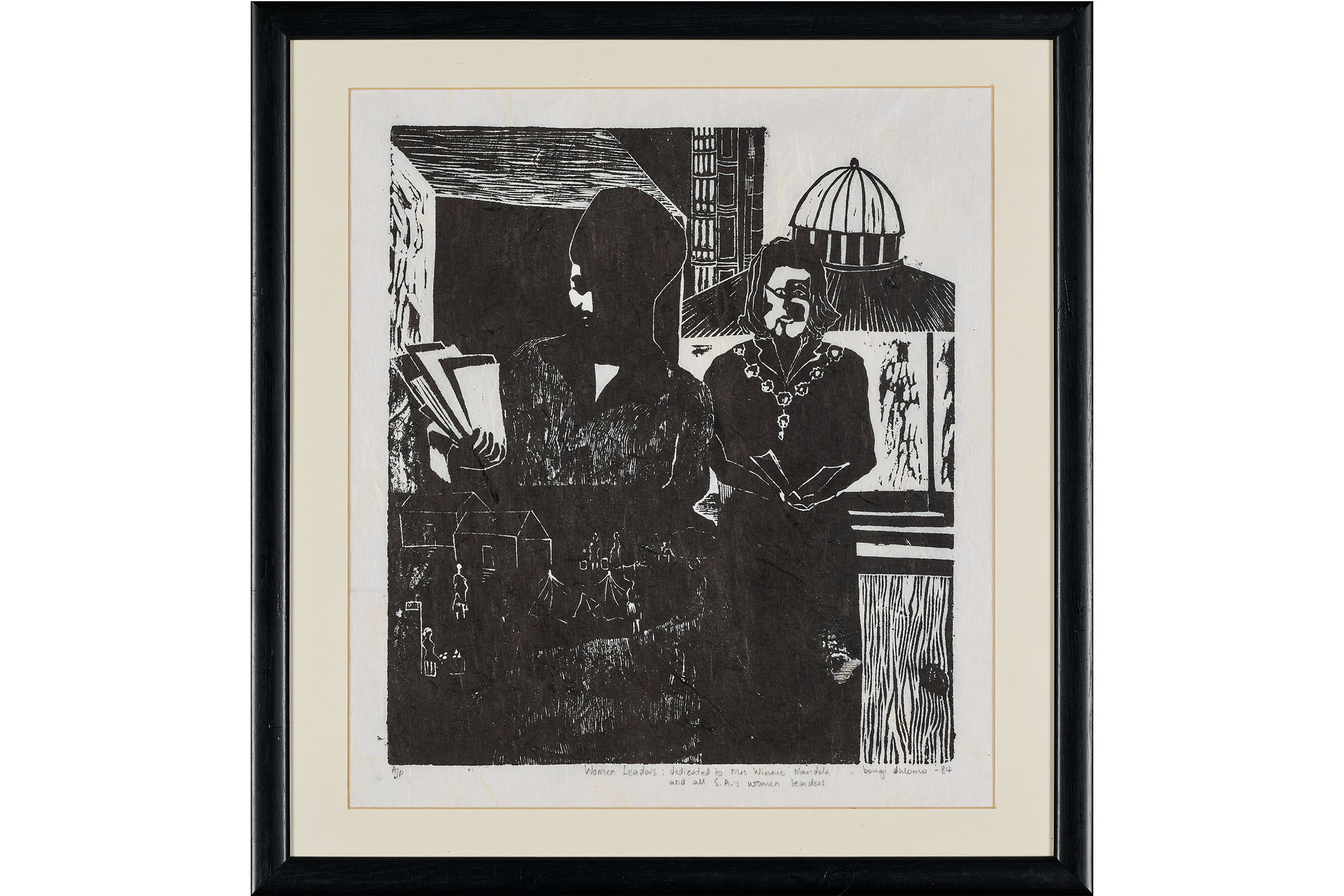

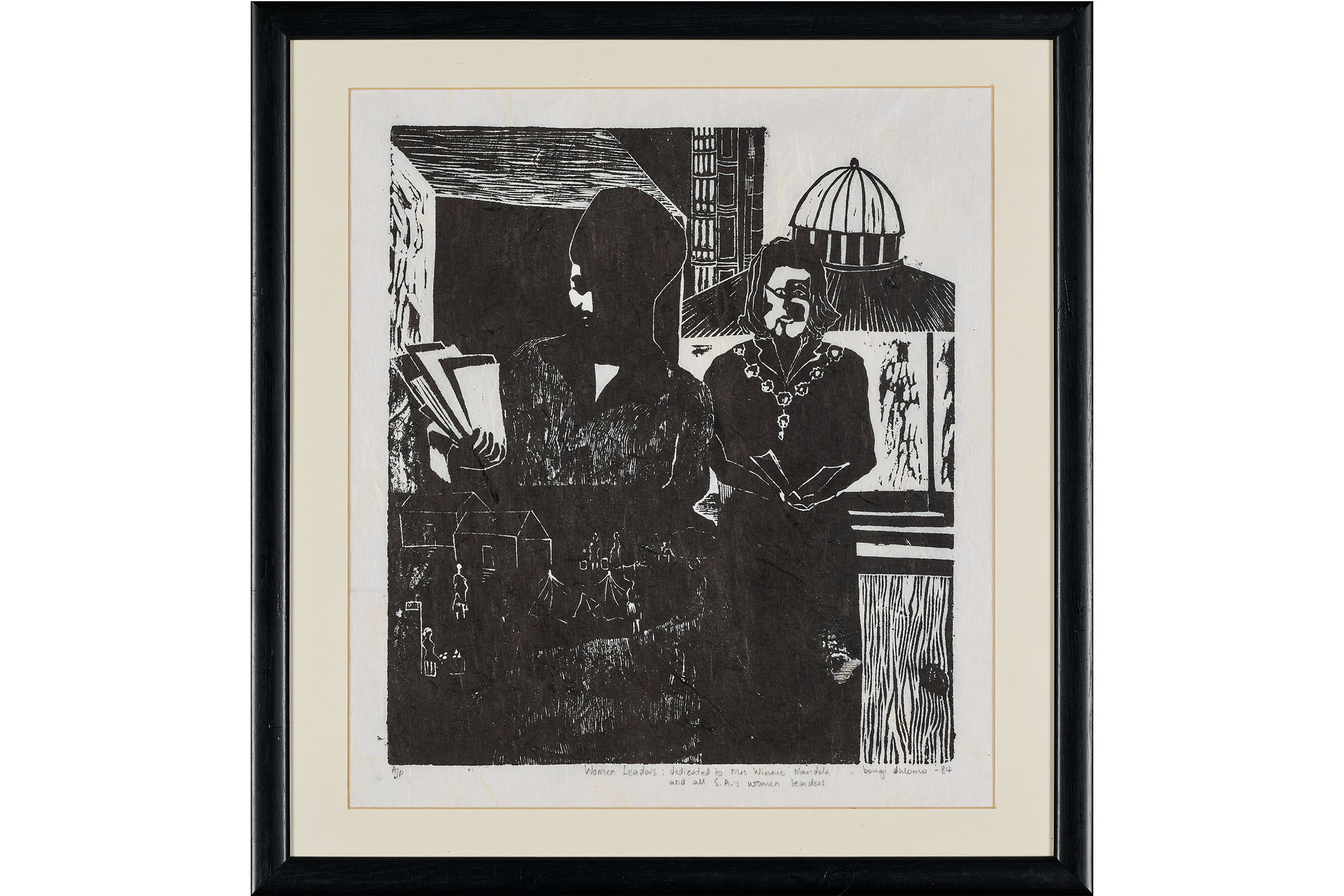

Entering the “Political” room, Ruth Motau’s iconic colour photographs of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are juxtaposed with Bongi Dhlomo-Mautloa’s 1984 etchings for Madikizela-Mandela. Yet, the political is not straightforward. There are earlier black and white photographs by Motau, taken while “working in the thick of gunfire at times”: her sensitive portrayal of apartheid’s conflicts and everyday interactions in townships. Noria Mabasa’s clay sculptures with enamel paint are equally complex. Here, we have both South African Policemen, 1987 and various others of ordinary Black men and women. There are many more images in this room. Individually and collectively, they are rich testimony to the complicated and divergent ways in which Black South African women artists have shaped political thought, space and activism. They trouble the dismissive label “protest art”, which has so effectively stifled critical engagement with heterogenous Black creative production under apartheid.

Motau appears in many other rooms as well. Well known as a documentary photographer in the media, her work is seldom considered for its aesthetics. Yet, here, in different rooms of the exhibition, sometimes with multiple images grouped together, an artistic signature is evident. Through such illumination, the curators ask us to rethink not just Motau but also the very entanglements of categorisation and evaluation at play here.

Multiple readings

The room titled “Love| Pleasure| Intimacy” underscores “the manifold ways in which concepts may be reread and even thoroughly challenged in the entire exhibition”, as the wall text reads. Here, an image of sibling rivalry shares space with photographs of the first gay marriage in Soweto, or an exploration of affection through Biblical reference.

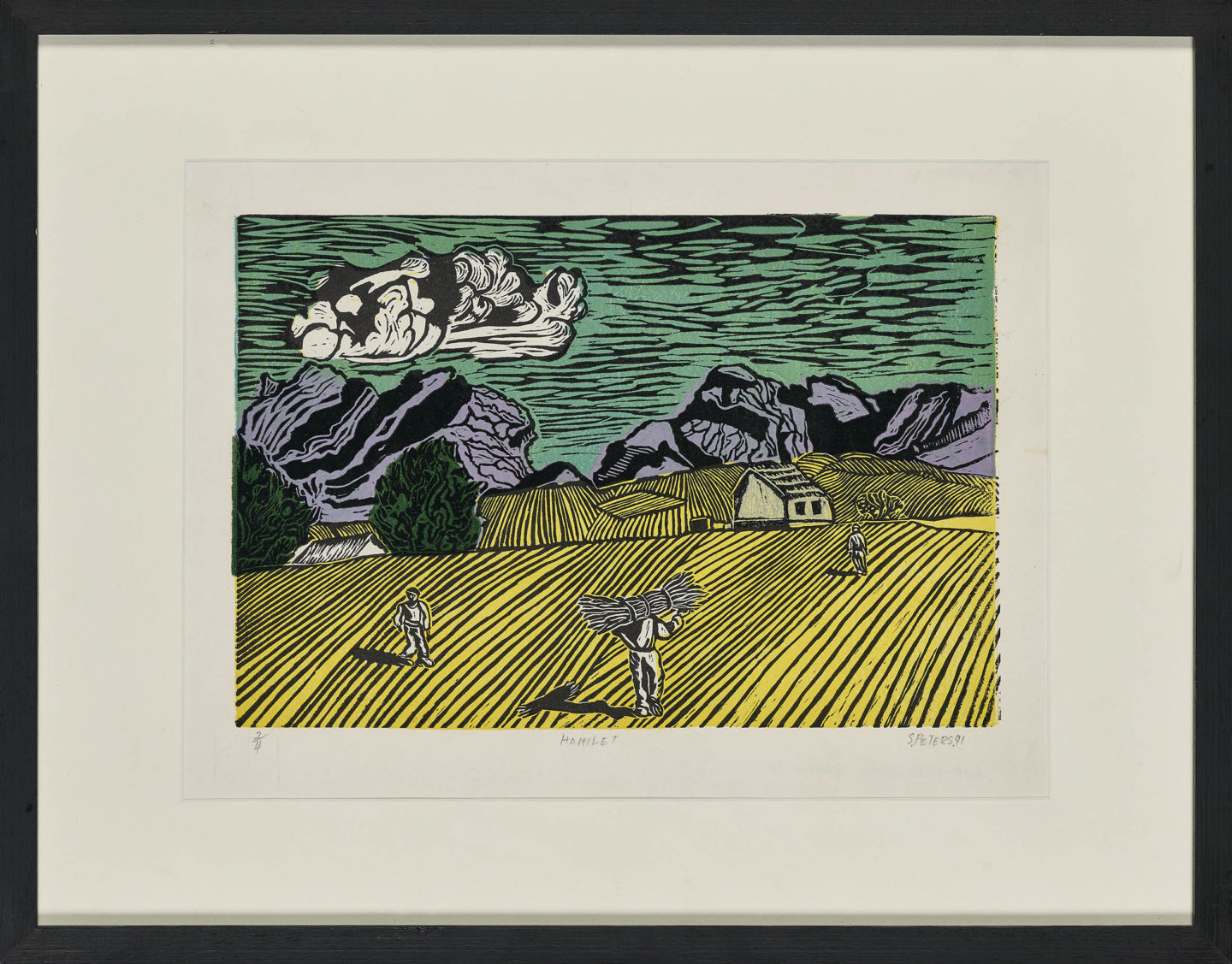

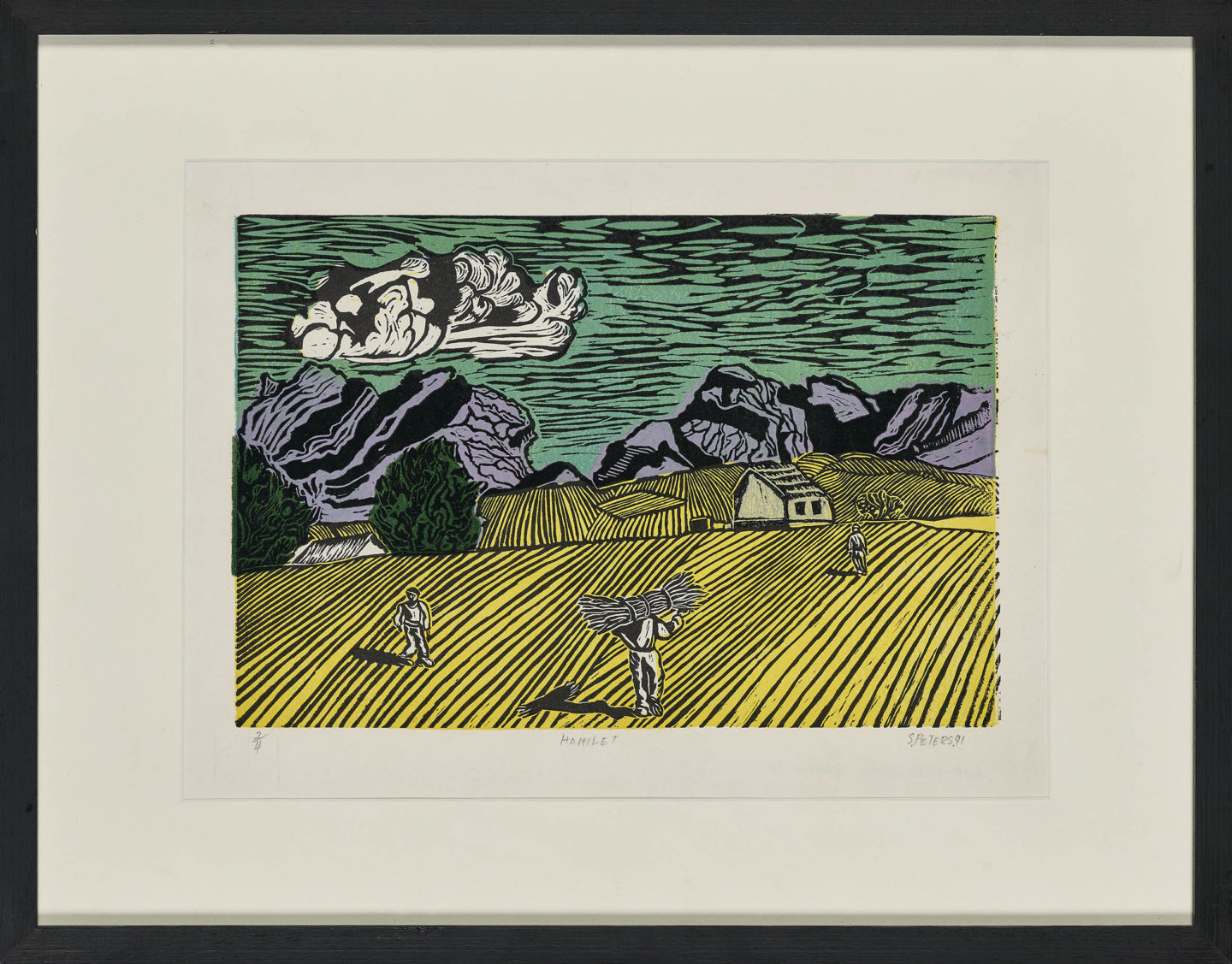

The “Landscapes” room holds physical and conceptual landscapes such as Mabunda’s rings, Bongi Kasiki’s imposing birds or the mythical in Emily Mkhize’s Geometric Design tapestry in white, grey and reds, which eludes immediate placement – another way of speaking about its genre and its inspiration. Sophie Peter’s black and white linocuts Boland, Vredenhof and Endless Winelands invite recognition while withholding the certainty of location, as much as her colourful Hamlet, with its green sky, grey mountains, golden land and three small human figures in different parts of the frame.

Several artists reappear across the different rooms of the exhibition. This should be unsurprising given that artists habitually explore different themes and creative registers. And so, with each encounter with Valerie Desmore, Nombeko Mpako or Gladys Mgudlandlu comes a deepening appreciation of their artistic range. The repeated encounters with Desmore and Mgudlandlu also do something else. Although Mgudlandlu is often credited as the first Black woman to exhibit at a public art gallery in South Africa, Desmore’s public critical engagement predates this, a sobering lesson on the status of “firsts” that Ntombela and I have explored elsewhere. The celebration of the “first Black woman” often ignores the violence behind this delayed arrival, and such violence’s reach beyond the broken boundary. The status of “first Black woman” is no insurance against obscurity. Furthermore, once we accept Mgudlandlu as “the first”, we may never know to look for Desmore.

Desmore’s recurring work alerts us to an additional dimension of the exhibition. Her paintings are not always recognisable as hers. Partly because of her critical neglect, one tries to make sense of her work anew with each encountered painting. Yet, she is difficult to pinpoint.

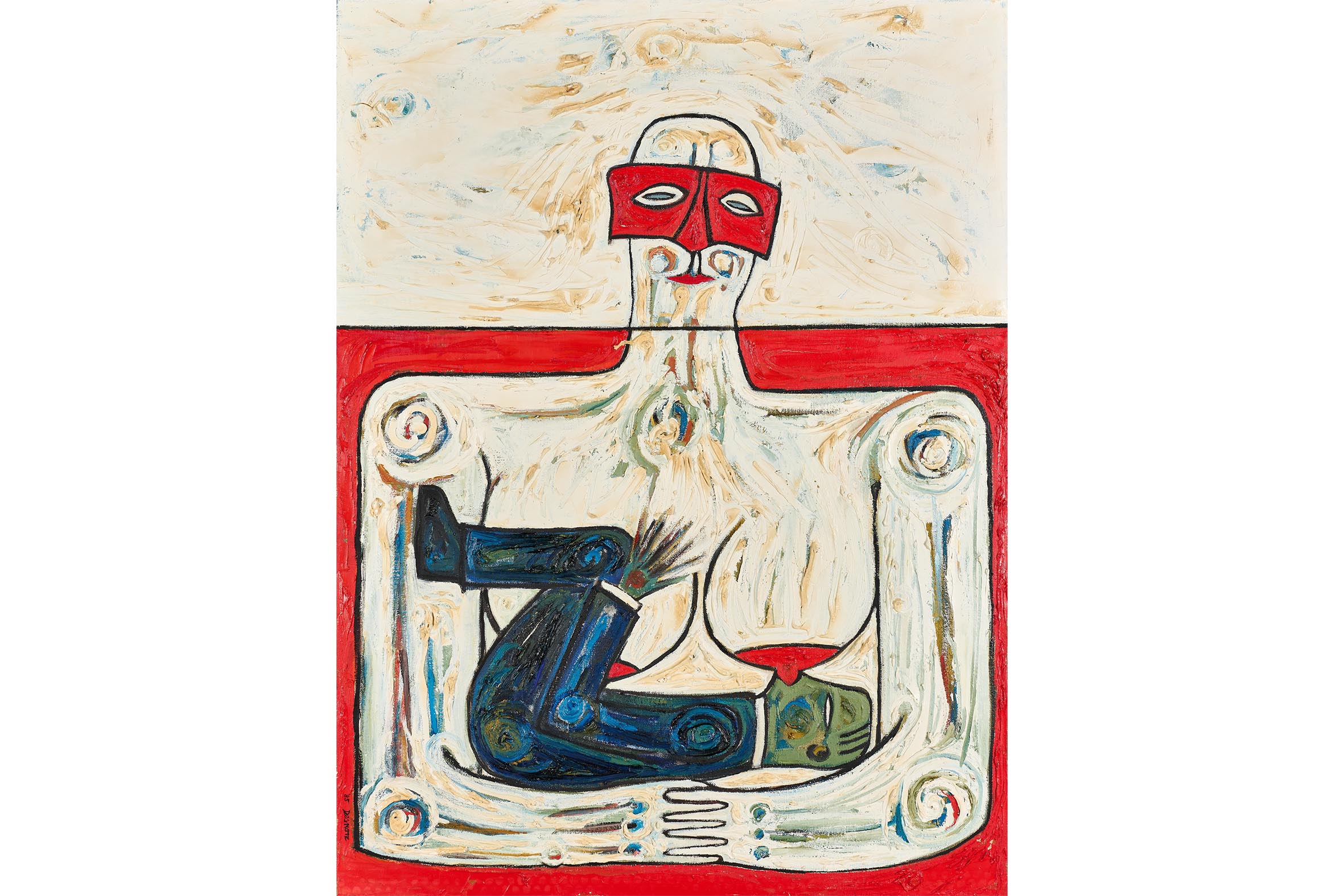

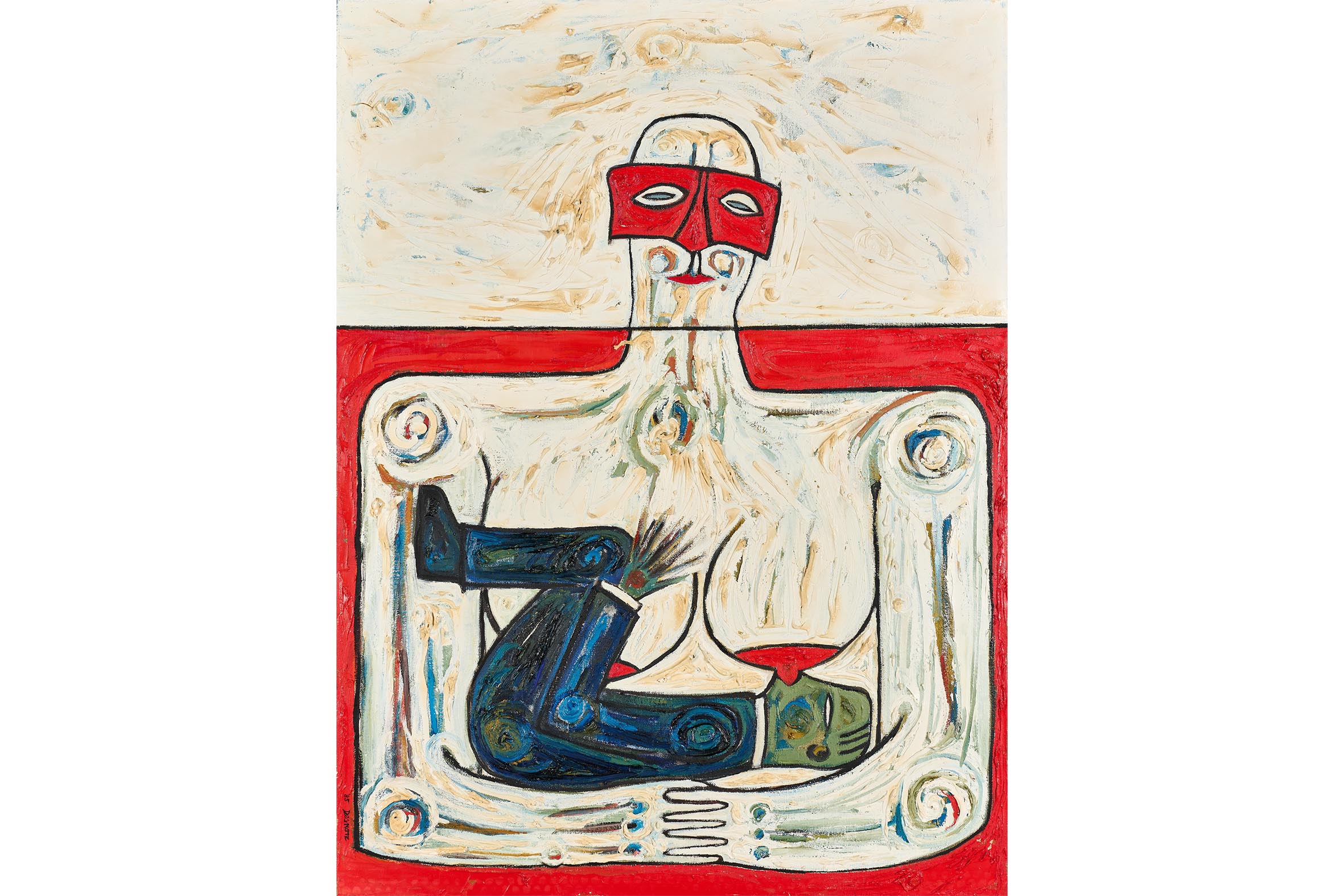

Her 1958 painting Fright is reminiscent of other more famous proto-expressionist paintings. By 1985, she was engaged in a project that seems prophetic. Her paintings The Hunger and Red Madonna reach into our present to offer incisive critique on the vulgar intersections of consumption, misogyny and aesthetics. The dark greys and blues of the ominous Street Accident pull us in yet another direction. It is true that artists change techniques and influences all the time. Yet, we are trained to look for continuities and connections, and when these are hidden, to seek out critical reflections on an artist’s work.

Reflecting on her prolific and determined production and experimentation across several decades is both awe-inspiring and devastating. Given her pioneering status, the length of her productive years, its stages, and her range, her obscurity makes no sense. In this exhibition, Desmore’s repeated appearance on unrelated themes is an invitation to many belated sense-makings. Itinerant and scattered as the archives of Black women artists are, the exhibition When Rain Clouds Gather delightfully and provocatively plays with what gathering such archives might produce. There is no obsessive focus of comprehensive cataloguing and mapping or hankering after an impossible project of constituting a complete archive here. Malatjie and Ntombela’s curatorial genius lies in presenting us with Black South African women artists as a generative archive. The generative is, after all, the very heart of artistic practice.