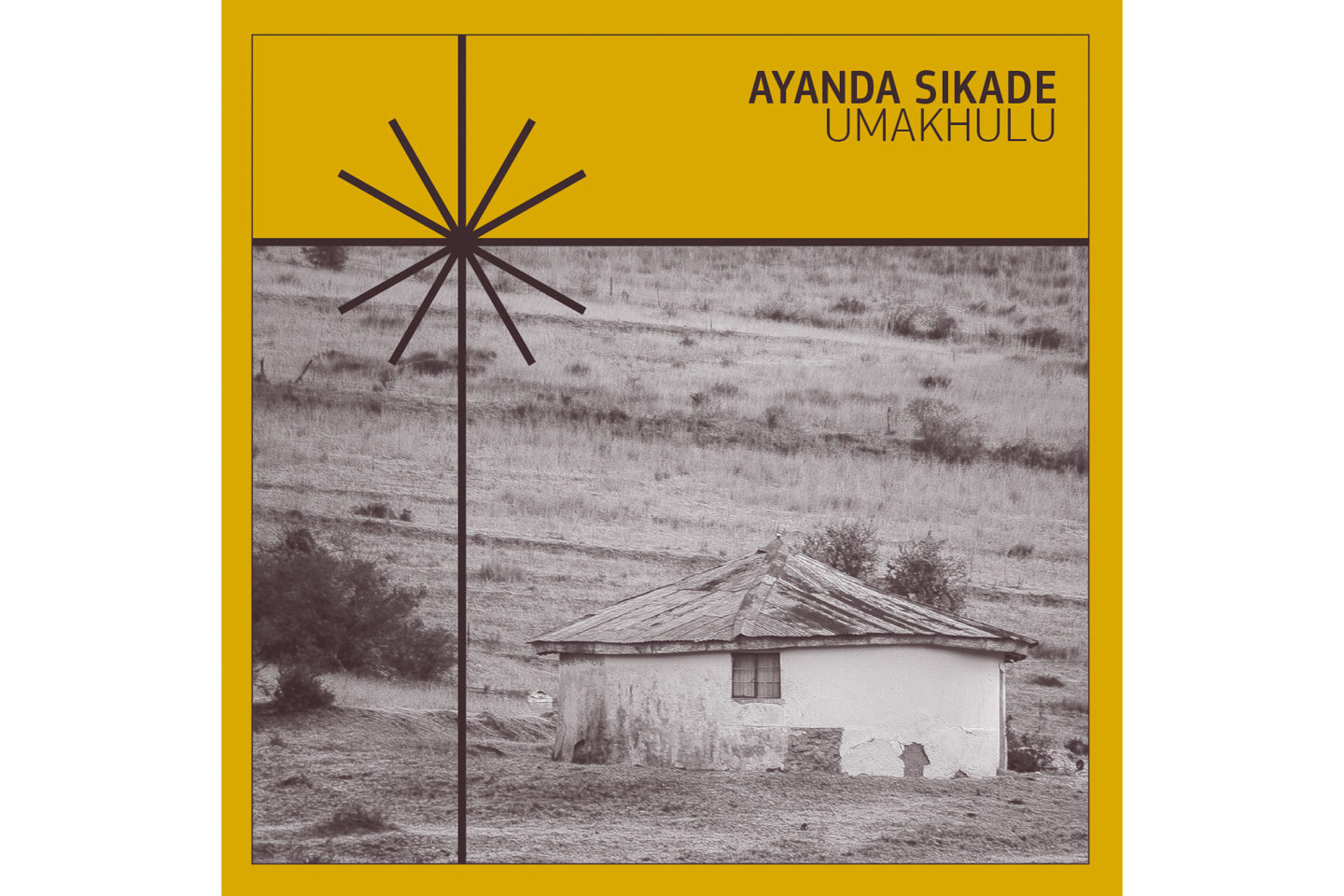

Ayanda Sikade honours his grandmother on ‘Umakhulu’

The drummer has fond memories of his childhood home in Mdantsane, where his grandmother allowed him the freedom to immerse himself in music. Hence his latest album is dedicated to her.

Author:

14 January 2022

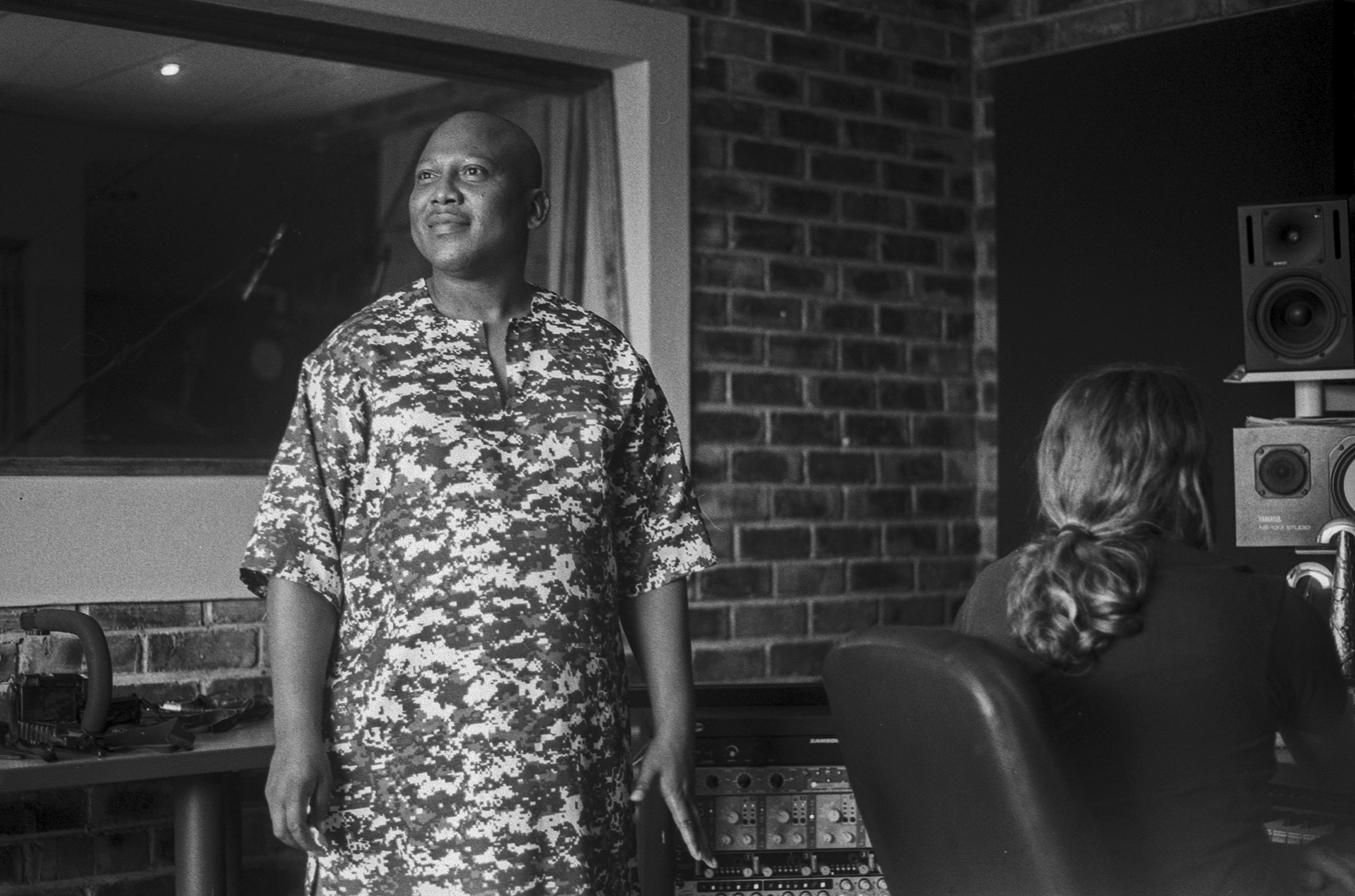

Known to all by his signature phrase – “It’s on!” – drummer Ayanda Sikade has always been ready to step up to the bandstand. Having shared the stage with many great masters of South African jazz, he has absorbed those influences and deftly channelled them into his latest album, Umakhulu, released in December 2021.

Umakhulu, which translates to grandmother in isiXhosa, is an ode to that grand matriarchal figure who was important to Sikade’s life as he grew up in East London. Sikade’s buoyant presence, infectious laughter and jovial energy are palpable even over the phone. “She was my friend. I was very close to her. Ever since I was born, she was there. She was a big pillar of support and strength to the family as a whole.” Memory, history and his own roots inspire the stories in this sophomore work.

The album opens with Mdantsane, a beautiful traditional jazz-inspired ode to the East London township. It sets the tone for the dedication to his grandmother. Sikade was born in the village of Kwetyana but, before he turned one, went to live in Mdantsane with his mother and grandmother. He was raised there, and left only when he went to university.

“Without Mdantsane in my life, I would not be a musician today,” he says, “because [there] I was exposed to many cultural activities and music was one of those. That house was so significant for my musicianship and for me to learn and understand the music that I’m dealing with now.” He also speaks of the Mdantsane Drum Majorettes, whose drum patterns he used to imitate.

Across the road from where his grandmother lived was a space where musicians would come to rehearse. “Bra Tete Mbambisa, Bra Tally Goduka, Tex Nduluka, Lulama Gaulana, Pat Matshikiza … and all these great masters used to rehearse [there] back in the late 1980s,” he says. Sikade would come from school, change his uniform and then cross the street to be with them. “I used to be there every day of my life.”

The Eastern Cape also has a rich musical heritage, especially in jazz, though it is often overshadowed by the focus on larger cities. “The Eastern Cape has been the hub. All the great musicians of South Africa used to learn music there – particularly East London, from back in the 1950s and 1960s, because they’re coming from that side,” Sikade says.

“Bra Johnny Dyani was from there. Mongezi Feza from Queenstown would go to East London; even Bra Winston Mankunku would go there. The grootmans [a term of respect for an older man] from The Soul Jazzmen in Port Elizabeth would go there. They were all going back to East London to grasp something in this music.”

About these roots, Sikade adds: “That music is a part of me. It’s always going to be with me forever. I’m really happy that I could also remember it.”

Inspirations and some learning

This music education from such an early age exposed Sikade to the sound of jazz, naturally, and to an assortment of musical instruments. “The reason I’m playing drums was because that was the only instrument I was allowed to touch. After rehearsals the cats would go for a break; a smoke break, or get some beers.” He would be surrounded by electric pianos, saxophones, trumpets, basses and drums.

“If you don’t know an instrument, you might break it. But with drums, it just sticks on the skin, so I would go bang on them for a bit and no one would say no. I would also try to learn how to imitate what the drummer was doing when playing his song, or figure out a rhythm for instance.”

When he left Mdantsane, Sikade went to study at what was then the University of Natal in Durban after being invited by Darius Brubeck, pianist and the head of the music school, to join its big band. There he connected with local jazz musicians in and outside the university setting. “There were great musicians that were on the Durban scene, the likes of Philani Ngidi and George Mari. And uBab’ Brian Thusi, who took me under his wing. I played in his band called The Moneymakers.”

Anecdotes and fond memories about his childhood home feature on the album. One of the tracks, Nxarhuni River, takes the name of a significant river in the area. “The Nxarhuni would be the river that we’d cross after the Easter holidays when it’s time to go back to the township. Sometimes, you’ll find there’s only one bus stop, or there’s two buses per day. If you miss the one that is closest to you, then you’ll have to walk maybe five to seven kilometers.

“So, on some days, the Nxarhuni river will be full. My big brother would put me on his shoulders or other bigger guys would help us cross. It’s a significant story in our upbringing.”

Describing how he composes, he talks about a time when his car broke down, forcing him to do regular short trips to the shops. “On the way, I [would] sing … because when I’m alone, I’ve got company, which is my music. A melody or a bassline will come up and then I will just get high on this thing.” He sings a phrase to illustrate.

Additionally, he is inspired by the emotions situations evoke through memory. Spaceship, he says, is based on the memory of train travels in Europe. With Nxarhuni River it is something similar. “I can see it all again, because there was a certain emotion that was happening when [we were] crossing the river.

“Sound is my accompaniment, it’s my friend. In Spaceship, I’m sitting on a train and I’m just looking around at these mountains. Or sometimes in the plane, I’m just checking out the sky or the clouds and a song will come to me and accompany me while I’m looking at the scenery … All this music is composed like that. It’s really attached to the emotion of what has happened in my life. It is a journey and now I can put all of these sounds together.”

Everybody shines

Owing to his years of experience as a musician, Sikade never makes Umakhulu feel like a drummer’s album. It is not peppered with long intros or extensive solos. Instead, he gives space and presence to the various players in such a generous way that they’re allowed to shine.

Nduduzo Makhathini, with whom Sikade has a long-standing relationship, and also played on his debut album Movements (2018), features on piano. Young saxophonist Simon Manana’s tone is exquisite throughout the record – all helped along by the bass of Nhlanhla Radebe.

The trio of Sikade, Radebe and Manana played various compositions together for a few months before a selection was cut for the album, which was recorded by Peter Auret at Sumo Sound in Johannesburg. The entire album was recorded in one take.

“The truth and honesty is in the first take, so even if there’s a mistake, we keep it. Music must be recorded with its own mistakes.” That mistakes can be beautiful is a [lesson] he got from the late Zim Ngqawana. “He would tell us that ‘music must come out of its own ugliness, if it’s ugly, but if it’s pure and it’s original and honest [then that is] most important’. I believe in that too … Bra Zim played a big part for me to understand the sonic and to be honest.”

The album is distributed by Joburg-based label Afrosynth in collaboration with Rush Hour Records in Amsterdam. It is due to have a vinyl release in the coming months.

His umakhulu’s impact

Whereas Movements was an album about travelling between cities and establishing himself in Johannesburg, Umakhulu is a work that recognises the impact Sikade’s grandmother had on his life and music.

“She was a domestic worker, and even though she never went to school she was a first-grade Xhosa woman.” He describes going to work with her as a child on some days when it was cold, going into apartheid-designated white areas where she worked and playing with the toys in those houses.

“My grandmother was also a musician in a way, a traditional musician. Her character was so huge [and used to] reach a lot of places: from the township in Mdantsane … to the villages in Nxarhuni.” Sikade grew up around traditional music sung by his mother and grandmother, as the family did not own a record player.

Based in Pretoria, Sikade has been enjoying hand-delivering the album to his fans. “My grandmother was a very well-known person and I thought if this is her project then I have to really go all out as well, to emulate her spirit and to be like her. [I] put myself in her shoes. What would she do if she had something dedicated to her?

“It comes naturally because it’s never a struggle to have a big heart. So, I thought, let me just do that. And the reason for this is that I want this music to reach everyone. It is satisfying to see the appreciation people have just to have the CD in their hands … to see them smiling and appreciate it like that, before even hearing the music. It’s really humbling.”

The album has had a great reception in a short period of time locally and internationally, Sikade says. “That was who umakhulu [was] – the one that really goes all over with her spirit and her heart. So the response really matches who umakhulu was.”

Launches of the album are planned for Durban, Cape Town, Johannesburg and East London in February.