Aubrey Mokoape: A revolutionary with a human face

Many activists who were at the forefront of the fight against apartheid are not household names. Mokoape too. Yet, alongside Sobukwe and Biko, he fought. And only death stopped him.

Author:

5 February 2021

Maitshwe Nchaupe Aubrey Mokoape may have been the “short one” next to the much taller Steven Bantu Biko, but he remained a towering figure within the Black Consciousness Movement and in the broader South African struggle for a more equal society until his death on 26 December 2020.

The 76-year-old Mokoape, a medical doctor, died from Covid-19 complications at his home in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. He is survived by his wife Pomla, three children and several generations of activists, thinkers and ordinary South Africans who were influenced by an incisive mind that was matched by a profound empathy for local people’s struggles.

Related article:

This was encapsulated in his 2015 address to the Black Students Movement (BSM) at the university currently known as Rhodes University, during the Fees Must Fall protests. Mokoape urged students to understand the interconnectedness of struggle and build relationships between themselves, workers and oppressed communities.

“We who were the students of Saso [the South African Student Organisation] and the BCM [Black Consciousness Movement] have, and are continuing to travel this path of questioning, being amidst our people and learning from them, learning from books about the experiences of people elsewhere, teaching and conscientising, identifying and exposing the evils of the system and mobilising and organising our people for liberation. This is the solemn and historic duty of BC [Black consciousness] in our country. BC is not a dogma, it is a scientific and contextual guide for understanding, conscientising, organising in the quest for what Steve called ‘The quest for a true Humanity’ which in our view can only find expression in a Socialist society,” Mokoape said.

As a child, Mokoape experienced apartheid’s oppressive and nefarious machinations first-hand – Bantu Education and his family’s forced removal to Soweto being indelible examples.

In an interview with David Wiley, for the Overcoming Apartheid archive project, he described the Pebco bus strikes of the 1950s as his “political baptism”. This fire led to a teenage Mokoape being present at the formation of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in 1959.

Related article:

Coming under the influence of PAC leader Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, Mokoape accompanied him as they sought to hand themselves over to police as part of the protest campaign against pass laws on 21 March 1960. It was also the day of the Sharpeville massacre. Mokoape was arrested with 150 others and convicted of treason. He spent three years incarcerated at the Old Fort’s Number Four prison in Johannesburg. At 16, he was South Africa’s youngest political prisoner at the time.

On his release, Mokoape enrolled to study medicine at the then University of Natal’s Non-European section where he became a contemporary of, among others, Biko. Initially, politicised Black students on campus were members of the white-dominated National Union of South African Students (Nusas).

A state of mental bondage

As Mokoape remembered in that 2015 BSM address: “We blissfully referred to ourselves as Non-Europeans or Non-Whites as we deliberated about oppression in our student body meetings. We hardly realised how self-demeaning and self-deprecating we were. We were in a state of mental bondage, even while we were railing against oppression. We were labouring under ‘false consciousness’. Steve would later write that: ‘The greatest weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed’.”

Mokoape described how engaging in the “dialectical process of struggle” lifted the “fog” from their eyes and reinforced the realisation that “our interests and those of white students differed diametrically. They wanted to reform the system, we wanted to overthrow it and reclaim the conquered land. We realised that, as TS Elliot stated, ‘There can be no peace between hammer and anvil’.”

Related article:

This radicalisation would lead to Biko, Mokoape and others walking out of a 1967 Nusas conference held at the university then and currently known as Rhodes University in protest at the student leadership acquiescing to the laws that prevented Black student members from staying on campus during the conference.

They would go on to form the South African Student Organisation (Saso) later in 1968 and then the Black People’s Convention in 1972.

Mabogo More, who first met Mokoape as a student at the University of the North (now the University of Limpopo) in the early 1970s, felt that “Aubrey carried into Black Consciousness some of the ideas that came from the PAC… There was a lot of discussion at the formation of Saso around the concept of being ‘Black’ and who was to be included and who was not. Aubrey argued strongly for the exclusion of so-called coloured and Indian people but Steve was of the opposing, more inclusive view: that Black was a political identity, not a cultural one. Steve eventually carried the day and, by the time of the Saso Nine trial [in 1975 and 1976], Aubrey had also changed radically towards a more inclusive position.”

The Wentworth years

The medical school’s residence for Black students in Wentworth was a hotbed of Saso activity – and raucous parties – remembers Dr MR Haffajee, who was two years behind Biko and Mokoape. “There was a section of the residence called Mosquito-ville where Geez [Dr Goolam ‘Geez’ Abrahams, a close friend of the Mokoape family] stayed, and we would all congregate and there would be dopping and smoking and late-night discussions about all manner of political things. Sometimes the Malombo Jazzmen would be hanging out there, there were often readings and speeches and interactions with people like Fatima Meer and Rick Turner.”

Haffajee remembers Saso’s deliberate politicisation of first-year students starting in orientation week with a tour of the better-resourced whites-only Howard College campus. “The comparison to our campus and residence was very stark. Then came the exposure to the writings and thinking of people like Steve Biko, Richard Turner and others. We were young and impressionable and were soon all Black conscious. We were made aware of what was happening in the country and were certainly better informed than medical students at Wits or in Cape Town.”

Saso was given office space by the American Board Mission at 86 Beatrice Street in Durban’s downtown. From there, the Black People’s Convention would emerge in 1972. Mokoape, Biko, Strini Moodley and others would immerse themselves in the struggles around them, becoming more radical by the day.

A connection between students, workers, academics and communities that would lead to the “Durban Moment”, a period of rolling mass action and protests that included around 61 000 workers embarking on a three-month strike in the early 1970s.

Related article:

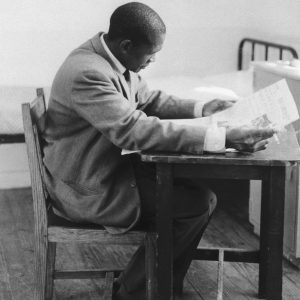

Siphesihle Zulu, a young school student in Durban in 1976, told the Human Science Research Council’s Remembering 1976: The Soweto Uprising and Beyond project that with political parties banned, the BCM filled a huge void for young people in terms of conscientising and organising. “When I was a young boy, my uncle, who was a pastor, lived in Beatrice Street. So I ended up… interacting with these people. I would see this tall man, that is, Steve Biko. And there was the short one, Aubrey Mokoape,” he said.

Mokoape would, together with several BC leaders, be arrested for breaking their banning orders and organising the 1974 Viva Frelimo Rally at Curries Fountain in honour of Mozambique’s independence and the hard-won victory of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, or Frelimo.

In the chapter ‘My Life on My Terms’, from Time to Remember: Reflections of Women from the Black Consciousness Movement, Pomla Mokoape remembered the panic and chaos that ensued when police tried to break up the rally.

A pregnant Pomla was set upon by dogs, one of which bit her in the stomach, causing her to lose her hold on her child Ntupang, who was thankfully scooped up by Bridget Mabandla. Pomla was rushed to King Edward VIII Hospital, where she was smuggled away from police custody by staff who knew her husband.

The Saso Nine trial

Two weeks later, while at work, Pomla received a call that “changed all the dreams I had for us as a young family”. Aubrey Mokoape had been arrested by the Special Branch together with other BC activists, including Moodley, Saths Cooper, Muntu Myeza and Mosiuoa “Terror” Lekota.

The trials of the Saso Nine would start two years later in Pretoria and Pomla remembered the “highlight of each day would always be the defiant entrance of the defendants, who would file in with their fists clenched singing”:

Asikhathali noma siyaboshwa (We don’t care if we’re arrested)

Sizimisele ukuthola inkululeko (We’re confident of gaining our freedom)

Unzima lomthwalo (The load is heavy)

Kufuna sihlangane (But we need to stay together)

The public gallery would rise as one to sing along, “using their voices as weapons against the mass force of injustice”, and “causing an electric charge to surge through the hearts of all those gathered”, recalled Pomla.

Tried under the Terrorism Act, Mokoape was sentenced to six years on Robben Island.

Pomla was allowed only four visits a year: “These quarterly trips to see the man I loved was what I looked forward to most in my life. In the lead-up to these trips, I would be so overcome with the combination of excitement and anxiety that I would find it hard to sleep. The trip to Robben Island across turbulent waters often made me sick. While I was excited to see him, I was also anxious about what physical or emotional state I may find him [in].”

While the waters around the Island were choppy, Mokoape, Moodley and the BC “activists from the streets” were causing turbulence on it. They knew the prison regulations and didn’t give a damn for them or even reputations. Or what they deemed the institutionalised complacency of leaders like Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and others from the ANC and PAC who had been on the island for years already.

Robben Island became a new site of struggle where Black humanity was reasserted and reform – including better food, living conditions, access to newspapers and so on – demanded. The BC prisoners beat back the dogs unleashed on them when they protested, they poached wildlife on the island for braais, clenched fists in greeting to other prisoners in full view of warders and eventually caused the prison authorities to set up another section just for them: “A Section” or “hardegat” (hard-arsed section).

As Moodley tells Paddy Harper in The Lighter Side of Life on Robben Island: “By 1978 – and I am proud to say this, and I challenge any prisoner to disagree with me – we of the Black Consciousness Movement had revolutionised Robben Island.”

On his release in 1982 Mokoape returned to King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban to complete his internship. Haffajee remembered “how much he had shrunk. He was a bulky guy before he went in, but he came out much thinner and much quieter.”

Haffajee was a surgical registrar at King Edward. And, of working with Mokoape, he says, “[it was] difficult telling Aubrey to do the things we get interns to do – you are essentially a gopher – because he was a political elder. But he never complained and did his work without hesitation. I think he just wanted to qualify as a doctor and get on with his life at that point.”

Never deterred

But politics would remain in Mokoape’s blood. Unemployment People’s Movement leader Ayanda Kota remembers seeking out Mokoape’s advice when he and other young activists were being purged from the Azanian People’s Organisation around 2001. “He encouraged us to leave and to reconstitute ourselves politically. He reminded us that struggle is not for sprinters, it’s for people with stamina. It is protracted, requires us to build solidly with communities and to connect with workers, students and those with indigenous knowledge,” said Kota.

This sense of struggle and effecting change in your locality is a trait that Nise Malange, director of Durban’s BAT Centre (multi-disciplinary workshop, exhibition and performance space) remembers most fondly about Mokoape.

Mokoape chaired the BAT Centre board from 2000 until his death. “He always insisted that the artists who came out of our programmes returned to plough back into this community and the next generation… Like most BC guys, ‘Doc’ was very concerned about the community around us [in the Victoria Embankment harbour area], that is why we have things like the Inner-city Children’s Programme for immigrant and refugee children.

Related article:

“‘Doc’ led by example, he did outreach work at old-age homes as a GP and was really driven by education, especially Pan-African education, and he would tell the young kids that ‘even as an activist, you must educate yourself’ and used himself as an example,” said Malange.

More will remember the intellectual with a “photographic memory” who read and quoted Aimé Césaire and Cheikh Anta Diop widely, and held the view that the origins of philosophy were based in ancient Egypt (which he had visited) and not Greece.

With his booming laugh and love for ideas, books and people, Mokoape committed his entire life to a constant, daily revolution in everything he did.

In that 2015 address to the BSM, he recognised that this required “you [to] commit yourself to the struggles of the people – [in] the mines, on the farms, in the shacks and here at the university. When our people are in struggle it is our duty to join them. It is fulfilling to know that you are making an effort towards the betterment of humanity. Resist the arrogance and elitism that a capitalist education inculcates in the unsuspecting. Do not hanker after positions or glory. Rather immerse yourself among the people and be of service. Cultivate in your hearts a love for people and be patient and truthful with them. A revolution without love is no revolution.”