Ari Sitas’ poems revisit Ethiopia

In his republished collection, the South African poet, theatre maker and sociologist connects the dots between the country on the Horn of Africa and a song liberation soldiers sang.

Author:

16 March 2022

Any grassy or sandy field, riverside or rocky outcrop in and around Johannesburg can become a site for worship. Come rain or shine, dark or blue, the robed religious leaders and congregants of distinct Christian denominations praise in the open air. Occupying public spaces like this is partly a declaration of visibility and partly an aural statement – those within earshot might hear the song and pass it on.

Churches this independent – even of buildings – date back to the Ethiopianism movement that gained ground in South Africa more than a century ago. In an ironic twist of the colonial machinery that used religion as a tool of repression, some churches on the African continent became the bedrock on which decolonial political movements organised. From the 1860s onwards, these polities responded to both colonial Christianity and to colonialism itself, organising from within church structures. The distinctive and unique features of these churches symbolise the shift from Christianity in Africa to African Christianity.

Ethiopia was once a beacon for the decolonisation of governments and pulpits on the continent. Today, according to the United Nations, Ethiopia’s 16 months of conflict has displaced an estimated 1.6 million people.

As the country slides further away from its idyllic representation within pan-Africanism, the Ethiopianism-inspired churches – physically vulnerable to the elements – become a relic of an Ethiopia that was only imagined.

Chimurenga Books have recently republished two long poems in a collection by author, sociologist and culture worker Ari Sitas. Originally published in 2000 by Deep South Publishers, Slave Trades and An Artist’s Notebook, each a poem that makes up the collection’s title, are an unfurling of character, event and theme, which converge to make myths of places, people and times.

Slave Trades is set in late 19th-century Ethiopia and centres around a fictionalised character named after and inspired by the avant-garde French poet Arthur Rimbaud. On his choice of protagonist, Sitas told New Coin poetry journal: “I have always been a sucker for French-tinged literature. I suppose it is part of my unconscious, raised in colonial Cyprus within an extended family whose links to Beirut and Cairo and to the French language was seen as a mark of distinction, and where English was a mark of drudgery, you are bound to develop biases. It helped that Arthur Rimbaud left a mark on the island on his way to Ethiopia and I suppose alongside Aimé Césaire he has been a defining influence.”

In Slave Trades, Sitas incarnates Rimbaud along with the courtiers, marketplace goers and importantly the religiously devout by allowing each character to speak their world into the reader’s imagination. Each worldview appears distinct yet bound to the poem’s zeitgeist.

Ethiopia, then and now

In November 1892, the time Sitas writes about in Slave Trades, Mangena Mokone established the Ethiopian Church in South Africa. Nigerian theologian Ogbu Kalu wrote about the expansion of Ethiopianism and pan-Africanism during this time, explaining that “Ethiopia became a symbol of African redemption, political and religious ideology that continued to inspire through generations”. So Sitas’ work draws temporal threads here, using history as a sub-plot for Slave Trades and for much of his other works.

After baptising the reader in the waters of fact flowing into fiction, An Artist’s Notebook wades into an Ethiopia brimming with agency and mundanity in 1990. This long poem follows urbane jazz musician Mangesh and his friend Abdullah as they search for a sense of meaning behind what has befallen their country. An Artist’s Notebook is how it feels to be drenched and heavy with the responsibility of having passed a rite of passage.

“I got close to Ethiopian affairs between 1993 and 2000,” Sitas says, “and my book Slave Trades was based on that unforgettable experience. My only friend from Tigray passed away three years ago, so the only news I get is from Addis and from mostly Amhara friends who are very critical of what the Tigray National Liberation Front is doing to the country at the moment. They admit that there might have been legitimate grievances but this must have been happening for some time.”

Republishing Slave Trades and An Artist’s Notebook brings Sitas’ decades-long cultural, organising and academic work back into focus. It ushers in a relook at his fascination with Ethiopia, its symbolism and its representation.

The roots of the story

During their time spent in military camps across the African continent, Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) trainees and operatives sang original and canonised hymns, choruses, military tattoos and folk songs. The vocal harmonies were sung to occupy the dissenters’ time and minds, to defy and to endure, to transport themselves and to imagine a different, better future. These songs reverberated from the camps all the way to apartheid South Africa and to the world.

Sitas says that one of the songs sung at MK camps and by dissenters in the country during South Africa’s violent transition to democracy precipitated a major theme in his work. “Etopia (A Week in the Life of a Worker in the Year 2020) [published in 1993], the novella that is to be republished,” Sitas says “was based on a song which made me wonder enough to find that its roots are from the so-called Ethiopian apostasy, from the white Christian churches in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

The song’s lyrics are: “S’phum’ eTopiya/Ethiopia. Sihamba ngomoya. Thina solal’emakhaya. [We are from Ethiopia. We will fly. We will sleep in our homes.]” These lyrics, written differently, appear in the poem Shrieks from Sitas’ Rough Music: Selected Poems 1989-2013 (2013). Sitas says, “The modern song, sung by the young comrades of the 1980s and in the Umkhonto camps referred to a mythical space because there were no camps in Ethiopia to fly home from.”

From the 1970s onwards, Sitas has published more than seven collections of poetry, most recently The Vespa Diaries (2018), and more than five works of fiction and non-fiction. His cultural work also spans from the most violent period of South Africa’s interregnum to a current collaboration with the Insurrection Ensemble.

Radical sharing

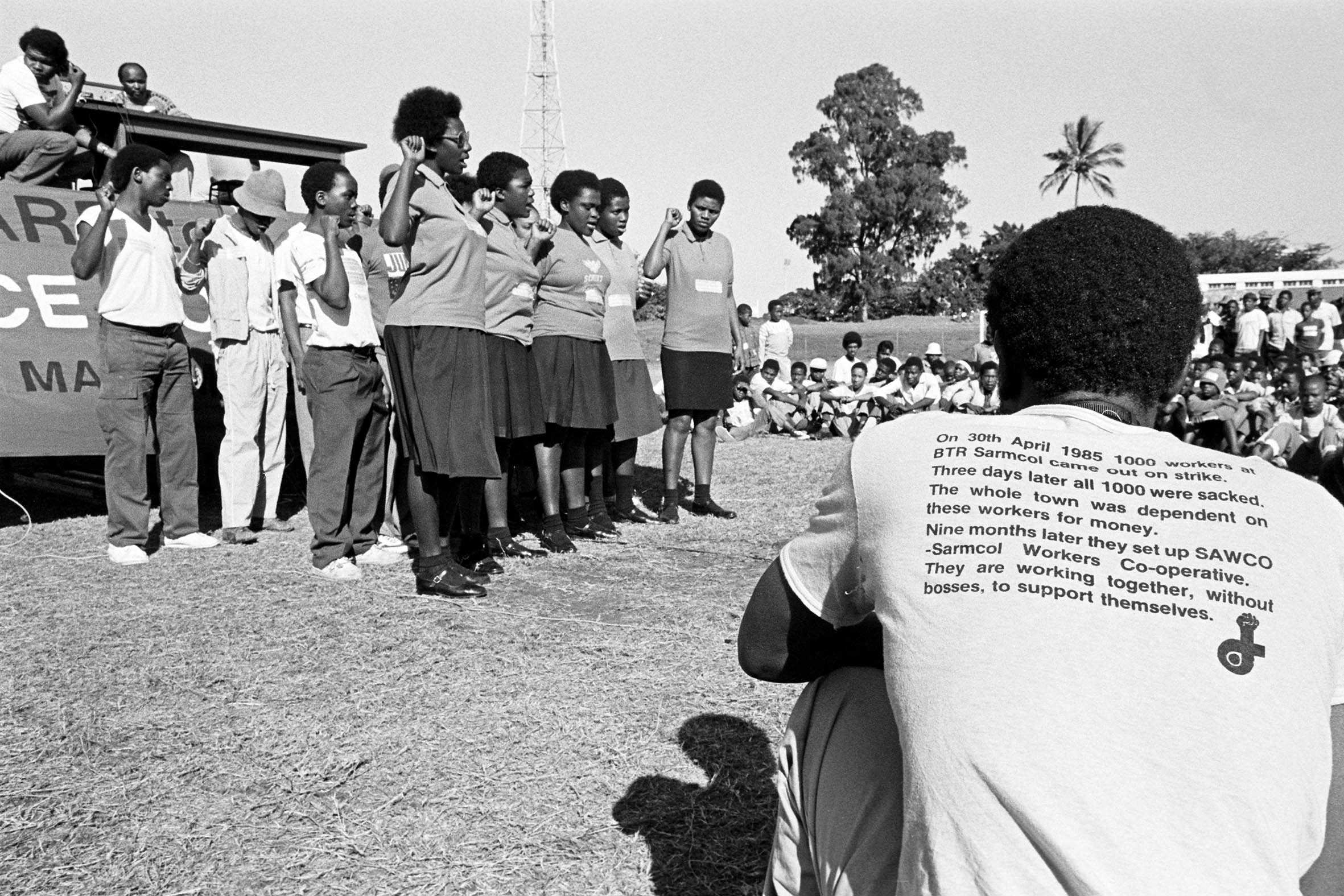

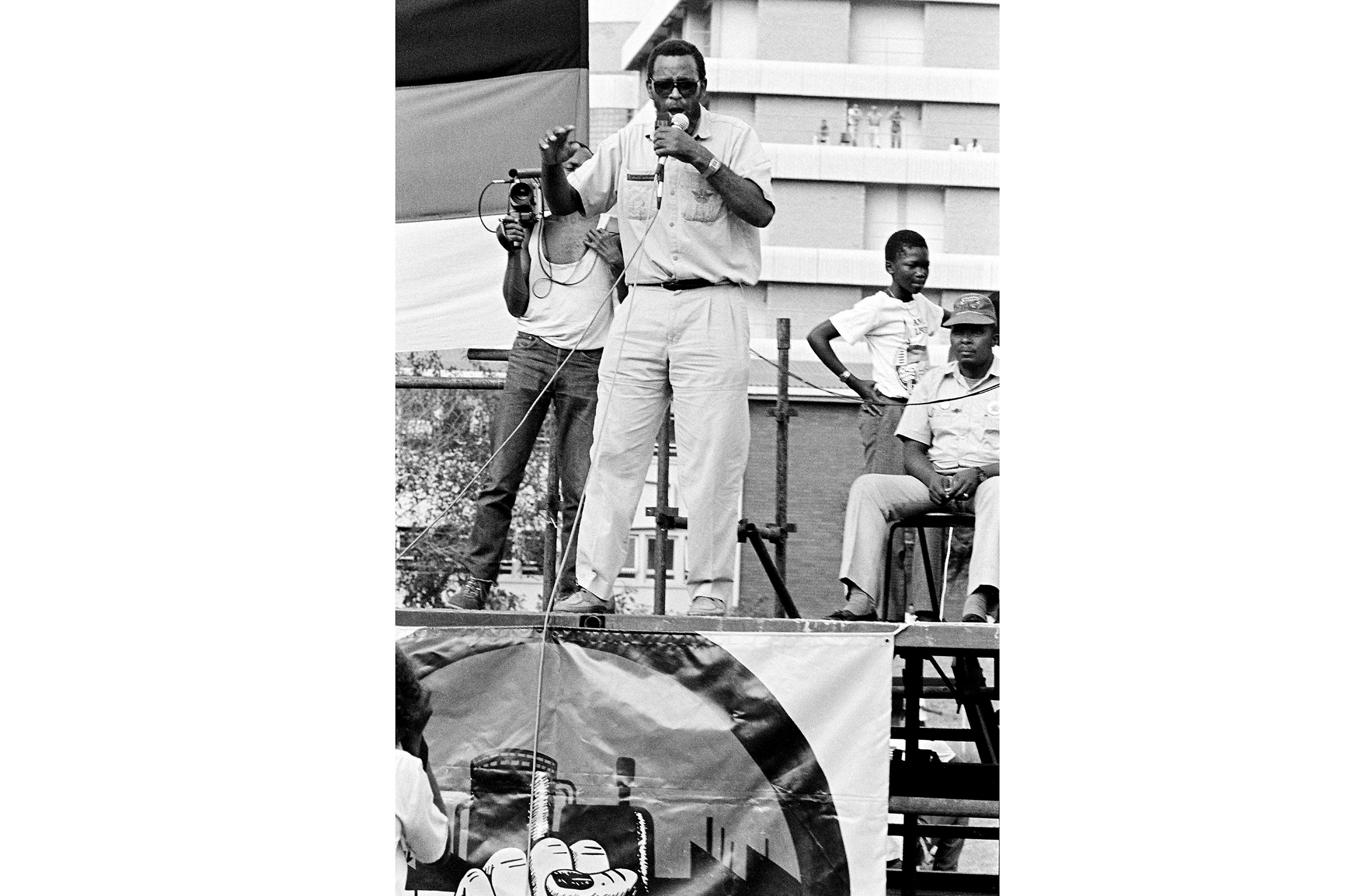

Sitas’ work, and a significant part of contemporary South African theatre and poetry, has the thematic and stylistic influences of art created in opposition to the apartheid system. The cultural work done in 1970s and 1980s KwaZulu-Natal by the Junction Avenue Theatre Company, the Culture and Working Life Project, the Durban Workers Cultural Local, the Federation of South African Trade Unions and the subsequent Congress of South African Trade Unions, and other workers’ movements served important functions in their time. The echoes of that work continue to resonate with theatre makers and audiences today.

“From the mid-1970s … we were working through Junction Avenue Theatre Company doing a lot of workshop-type theatre,” Sitas says. “We were working with Modikwe Dikobe and others, trying to do a theatre that was anti-apartheid and was increasingly one of the few nonracial companies in Johannesburg. There was always tension whether it should be in the theatre or whether it should be in the streets, in the church halls or the union halls.”

When striking workers were dismissed from the Rely Precision Foundry in 1980, lawyers representing the workers called in the Junction Avenue Theatre Company to use theatre as a way to extract statements from their clients. The ball got rolling when, in 1982, the theatre Sitas and Siphiwe Khumalo was producing in workshops with migrant workers living in Vosloorus’ hostels inspired the play Ilanga Lizophumela Abasebenzi.

“That put the word out that it was possible to do theatre in the labour movement,” says Sitas. “It started from small spaces, very confined spaces where meetings would happen. As unions started getting more and more confident, there were church halls, community halls, there were streets. So space was wherever there was a gathering of people. It was theatre that was happening in any space that allowed it to happen. Areas controlled by Inkatha councillors saw this as hostile activity, so they wouldn’t allow any performances happening there.”

Theatre during conflict

The culture organisations for workers, which Sitas was instrumental in forming and helping to run, created performances during a time of intense political warfare. For decades, the apartheid government had been forcing Black people from agricultural to factory work. Working conditions at factories were abysmal and pay was low and unfairly distributed. Workers’ unions were growing in membership and influence on both worker-related issues and on greater political affairs.

In 1982, the workers’ union at Natal’s Dunlop factory called for a strike. Sitas, who was then employed at the University of Natal, Nise Malange, Mi Hlatshwayo and Alfred Qabula responded to the creative call from striking Dunlop factory workers. “In Durban, by Sydney Road,” Sitas says, “the Dunlop people agreed to form the Durban Workers Cultural Local.” The organisation met at the nearby union offices and attracted participants who workshopped the seminal Dunlop Play.

“You had the Dunlop Play happening, then in Pinetown all of a sudden textile workers heard about that [and] they did their own. In Mpumeni, in Manzini they started their own. It started growing. Because the news went out, all of a sudden it became a national phenomenon. We weren’t ready for anything like that. But it was growing by imitation.

“Between 1982 to 1986, when the violence really started in [KwaZulu-Natal], there were about 2 000 people working in and through the labour movement doing performance. Not only plays, they [also] revived oral forms of poetry.”

What Sitas calls “trouble” is the radical sharing of subversive cultural artefacts such as songs, poems and plays at a time when they were undesirable and, in some cases, illegal. The song that Sitas heard about flying home from an Ethiopian military camp found its way to him through these processes.

“An aesthetic was being developed there and it was fascinating,” Sitas says. “Elements of it survive now in theatre that we watch over time. Elements of it have become almost commonplace because the teachers and others who are creating plays now were audiences during that time.”

The proliferation, syndication and imitation of music, theatre and poetry were as important then as they are now. In South Africa, the cultural canon must be an accessible and malleable tool to express contemporary reality. The melodies of church hymns can serve as the bases for dance anthems; poems can become advertisements; and performed against the backdrop of current conditions, anti-apartheid theatreworks can be poignant critiques of successive democratic administrations. It is not that nothing is sacred. The opposite, in fact. A work might be so usefully repurposed, time and again, that it is imbued with a significance that asks if its original creation might have been to be repurposed, now, in this way, for this particular cause.