Architect David Adjaye builds an African future

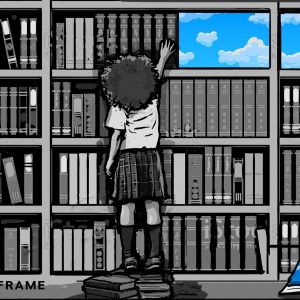

The designer of the Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library is guided by location, history and function when reckoning with both the past and the present that his buildings will reflect.

Author:

16 February 2021

Buildings are the structures that remain after the makings of the architect’s mind collide with physical environments. Architects conceive, design and model a speculative physical world in abstract, which is then realised as bricks are laid and pipes run. Eventually, people engage with the built environment.

While the buildings that appear before us are permanently attached to the minds that conceived them, their functions and significance change over time. Communities and precincts engage with and inform structures instead of being separate from them. In this and other ways, architecture affects us and is affected by us.

South Africa is a territory of rubble in purposefully shaped and positioned fragments inside larger clusters of fragments. Segregation continues to hold the country, especially its cities, together. Against the background of this fraught canvas, David Adjaye made a sketch on 12 December 2019 of what would become the design of the Thabo Mbeki Presidential Library.

Related article:

The library is the Ghanaian-British architect’s third project in South Africa, having been preceded by Hallmark House and the Hugh Masekela Memorial Pavilion, both in Johannesburg. He also has several completed and ongoing projects elsewhere on the African continent.

Adjaye’s process, which some argue is either devoid of or unencumbered by a particular style, is site-specific at its core. His main guides of making are the geographical locations and building materials historically used by the people in them; he merges the vernacular with cutting-edge architectural technologies and the functionality of spaces in buildings and their surrounding precincts.

For instance, in the United States, the structure of the Adjaye Associates-designed Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC was inspired by a sculpture of a crown-clad man by Olowe of Ise, a 20th-century Yoruba artist. The region where the Yoruba people lived had the largest number of Africans transported to the US as slaves. The building’s facade borrows its design from a fragment of the cast-metal architecture created by enslaved craftspeople in the American South, while the material used to create a dappled-light effect indoors is made from modern cast aluminium that was coloured bronze.

From past into future

Adjaye described the research process for the Thabo Mbeki library during the project’s unveiling on 20 November. “I seek not to, in my work, go into my imagination and draw, but to see if there are lessons from the past that can guide the way we look into the future. What I was asked to do with this work, the idea of looking back at the architecture of the civilisations and the gatherings and the communities of the continent of course came to mind. I looked at tombs and palaces, I looked at farmhouses. I looked everywhere and realised that these were specific forms and this type of building was something new that required its own articulation.”

What has been designed and is in the process of becoming is an L-shaped precinct in Riviera, Johannesburg. The main library building borrows from the design of granaries common to many pre- and post-colonial African settlements and civilisations. It comprises eight dome-shaped structures connected by a surrounding structure and has an underground basement area.

Related article:

The domed structures are red, after the mud brick used in the region since time immemorial, with apertures to take in light, thick walls to store warmth, terrazzo floors and timber cladding made from locally sourced stone and wood, respectively. Solar panels on the rooftop between the domes will generate electricity, helping to reduce the library’s carbon footprint.

“In the end, what struck me when looking between the images of the vernacular architecture was to notice that in all the communities of our continent, the science of the habitation of those communities was the ability to cultivate the land and to live with the land,” Adjaye said about the design. “And the secret of this was the technology that had, as it were, sustained those communities.

“In a way for me, it seemed like that the answer was staring right in front of me. But it was not what I thought it was. The answer seemed to be that we were talking about creating another store, another space. This time, it is not a granary store where one keeps seed for the future generations [which] sustains them and nourishes them and allows them to continue, but a different seed – a seed of the knowledge of the works of the great liberations and movements.”

Location and segregation

Forward-thinking as the library might be as a functioning monument to the African renaissance cultivated by former president and project head Thabo Mbeki, its fundamental flaw is neither in its aesthetic or function but in its location. Johannesburg residents overwhelmingly use public transport to traverse the fragments of the city’s townships, suburbs and districts.

From the Bree Street and Wanderers taxi ranks in the central business district, one can easily get within walking distance of the library’s demarcated site. But getting to either of these ranks from townships on the outskirts of Johannesburg is difficult – and emblematic of what makes the South African public transport system expensive and time-consuming.

Related article:

Economic and social inequality in South Africa is repeatedly reported as being the highest in the world. Spatial inequality, in particular, continues to derail the country’s development because this central ethos of apartheid is so hard to overcome. An International Monetary Fund study found that unequal access to opportunities is a central factor in the manifestation of inequality. Symptomatic of this, a Human Sciences Research Council report determined that the “relation between spatial location and the job-search strategies as used by youth may be pivotal” in finding a solution to South Africa’s crushing and sustained youth unemployment crisis.

The connections between space and other forms of inequality and historical oppression bear weight on the present.

Addressing related concerns about the planned National Cathedral of Ghana in Accra, a project partly shrouded in controversy because of what it will cost in a country in need of hospitals, schools and other public amenities, Adjaye said: “There isn’t necessarily a hierarchy of how things happen. To further progress, there are many projects of immeasurable merit, including those that can unify and reflect the nation together. The National Cathedral of Ghana is not just an important building reflective of the spirituality of the people of Ghana, but also a project that shows the confidence of Ghana at the beginning of the 21st century.”

African modernisation

Colonial modernisation encountered overt and covert resistance from peoples in various African locales. Architect and built environment scholar Manuel Herz gets to the heart of the issue when he writes in African Modernism: “Mirroring independence, the notion of modernisation in the African context is also not without problems. On the contrary, modernisation has a history that is deeply entrenched with the colonisation of the continent. Modernisation was one of the very motifs that the empires used to colonise Africa during the nineteenth century.”

South African cities, especially Johannesburg, are littered with the dystopian and now derelict remnants of zeitgeists past. Unlike the modernist architecture emblematic of and expressing the thrust of sub-Saharan Africa’s decolonisation era, the current era of African architecture has local technologies and peoples as essential considerations, shown by Adjaye’s critical consideration and thoughtful way of conceiving buildings.

The time and place we live in now is an African future envisioned by someone in the past, according to academic Raimi Gbadamosi. And in this time, the “progressive” architectural imperative cheek exists closer by the jowl of spatial inequality.

The Thabo Mbeki library design makes a metaphor of the granary storage technology that was essential to the existence and thriving of generations of peoples across the African continent. It envisions a space that, among other functions, will be a repository of African history and the legacies of its former leaders and a place of debate.

These exchanges, though, must reckon with the deeply flawed legacies of liberation movements across the continent – and Mbeki’s own in South Africa – so that those walls do not in themselves become a perpetuation of the exclusivity and segregation that make its location inaccessible to most.

As Adjaye’s approach attests, buildings – those that exist, those that are rubble and those that are in the process of creation – are aspects of who we are, who we are becoming and the reckoning with the complex histories, present and realities that inform them.