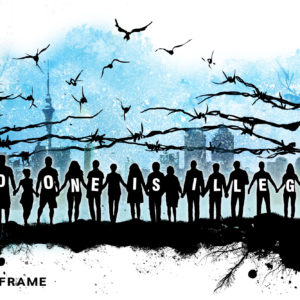

Anti-migrant sentiment is a national emergency

Hounding people born elsewhere is a form of bigotry, no less than racism or sexism. Those who believe in equal treatment for everyone should campaign against this prejudice.

Author:

1 April 2022

A new national disgrace has begun – and no one seems eager to stop it.

Its source is a problem that is not new but which has worsened of late – blaming migrants for this country’s problems. For decades, politicians have found mileage in portraying migrants as a problem. They have found willing allies in sections of the media and other voices in the public debate who are happy to decry the presence in our midst of people whose sin is that they were born elsewhere. In a country wracked by poverty and inequality, politicians have created a climate in which people are encouraged to blame migrants for their frustrations and, if violence erupts, are denounced as uncivilised by precisely the opinion formers who created the problem.

Related article:

The issue has now worsened as political parties and citizens’ organisations proclaim their intention to seek out migrants and to make them pay a price – they never threaten violence but they do create a climate in which migrants are likely to be targeted. Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema threatens to root out migrants who are working without the required documents. And the country now has a movement, Operation Dudula, whose sole goal is to “tidy up the road of South Africa” from “illegal immigrants” who it portrays not as people but as a polluting substance. Inevitably, violence has broken out in Alexandra township and in the Western Cape as a result of the war against migrants.

Political parties weigh in

Politicians and political parties have, as ever, made the problem worse while decrying it. Government politicians have reacted as they always do when migrants are attacked – they have condemned Dudula but continue to talk and act as if migrants threaten South Africans. Lest anyone suspect the government of being soft on migrants, it has tabled a law that will impose a ceiling on the number of migrants who can work in specified economic sectors.

Deputy president David Mabuza blames anti-migrant sentiment on the fact that “our immigration system is grappling with the implementation of stringent measures to deal with the influx of undocumented foreign nationals into our country, who ultimately compete with our citizens for limited resources to survive”. For him, the problem is not that migrants are targeted, it is that this task should be left to the government. Home Affairs minister Aaron Motsoaledi sees keeping migrants out as his core function. When pressed, he claims he is merely applying laws that restrict migrants – and so assumes that no one notices that his ministry drafts and ensures the passage of these laws.

Related article:

The Democratic Alliance has condemned the targeting of migrants – a shift from its 2019 election manifesto that stressed the need for tighter borders and more control on migrants. But its “solution” is a points-based system ranking migrants on “skills and education”. This sounds reasonable but is precisely the “remedy” proposed by British anti-immigration campaigner Nigel Farage. Points-based systems are usually used to favour people with resources and formal qualifications and to keep out hard-working, enterprising people who are impoverished and did not make it through school.

Herman Mashaba, leader of ActionSA, has been hounding migrants ever since his days as Johannesburg mayor when he claimed that FNB Stadium was in danger of collapsing because of the illegal mining activities of migrants (no one in the other parties or the media asked him to justify this claim). So, the ANC and opposition parties denounce attacks on migrants while portraying them as a threat, contributing to what they condemn.

People’s right to fairness

Among social justice campaigners, a march in support of migrants was organised by Kopanang Africa, a coalition of organisations that insist migrants are being blamed for the country’s problems. But that hardly amounts to a concerted campaign to protect people born elsewhere from discrimination and threats of violence. The lack of a campaign suggests that the social justice movements that influence the debate do not see threats to migrants as a priority – they will oppose them but not with the same urgency with which they pursue other issues.

But the threats against migrants are a national emergency. South African society, despite nearly three decades of democracy, remains divided between insiders and outsiders – and the most “outside” of the outsiders are migrants. The organisations migrants form have very little influence and there is no strong mainstream campaign committed to protecting their lives and livelihoods. Migrants are virtually friendless and unheard, at the mercy of any political entrepreneur who decides that, because they are the ultimate outsiders, they can be targeted almost at will.

There is a mountain of evidence that migrants are not a threat to South Africans – they are an asset. There is no evidence to support the usual claims that migrants take houses or jobs that belong to South Africans or that they are any more responsible for crime than locals. One example of inventing a threat to locals is the Western Cape anti-migrant violence, which was prompted by claims that residents of a shack settlement were renting out parts of their shacks to migrants: it is not clear how this disadvantages South Africans.

Related article:

Perhaps the claim most often heard about migrants – that they take jobs from South Africans – is particularly absurd. Yes, some employers hire migrants rather than locals because they can underpay them. But why can they exploit them? Because the law makes them rightless and subject to deportation if they are caught without documentation. Remove this “protection” for locals and migrants would no longer have their claimed advantage.

So, demanding immigration control and hounding people who happen to be born elsewhere is not a measure to protect the interests of South Africans – it is a form of bigotry. There is no difference between discriminating against someone because of their race or gender and doing this because they were born in another country. Targeting migrants is the new racism – it pretties up a prejudice against people as a patriotic act. We can also be sure that the migrants who bear the brunt of this assault are not the well-off people with qualifications who work for formal employers but those who have fled poverty or persecution. The anti-migrant campaign is a war against the impoverished as well as against people who are being bullied because of where they were born.

Given this, the fact that people are being hounded here should be a national scandal that prompts loud protest from anyone who believes all human beings are entitled to equal treatment. The campaign should target the real culprits – not the people in townships and shack settlements who blame migrants for their poverty but the well-heeled politicians, commentators and other opinion-formers who continually encourage them to blame migrants and, when they do, claim public opinion demands anti-migrant measures. And it should be led by everyone who claims to believe in people’s right to be treated with fairness and respect, wherever they were born.

The new racism is no different from the older variety. People who believe in a free and equal society should be as vocal in campaigning against anti-migrant bigotry as they are at calling out other prejudices.