Anthon Bosch is no stranger to adversity

Covid travel bans prevented the snowboarder from being the first to represent South Africa at a Winter Games, but he has no doubt he will get there and become a flagbearer for social equality.

Author:

13 February 2022

It’s going to be a tough few weeks for Anthon Bosch. Instead of becoming the first South African snowboarder to represent the country at the Winter Olympics, which began on 4 February in Beijing, he’s watching the Games on television.

The travel ban slapped on South Africans after the Omicron variant of Covid emerged meant Bosch couldn’t compete in the final Olympic qualification events in the United States and Canada. “I missed out on these last five events,” said Bosch.

“Sascoc [the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee] and Snowsports South Africa filed an official complaint to the International Olympic Committee [IOC] since we were the only nation that was discriminated against in this way, but unfortunately it didn’t seem to help. Even if they acknowledged the unfairness, [they said] there was nothing that they could do.”

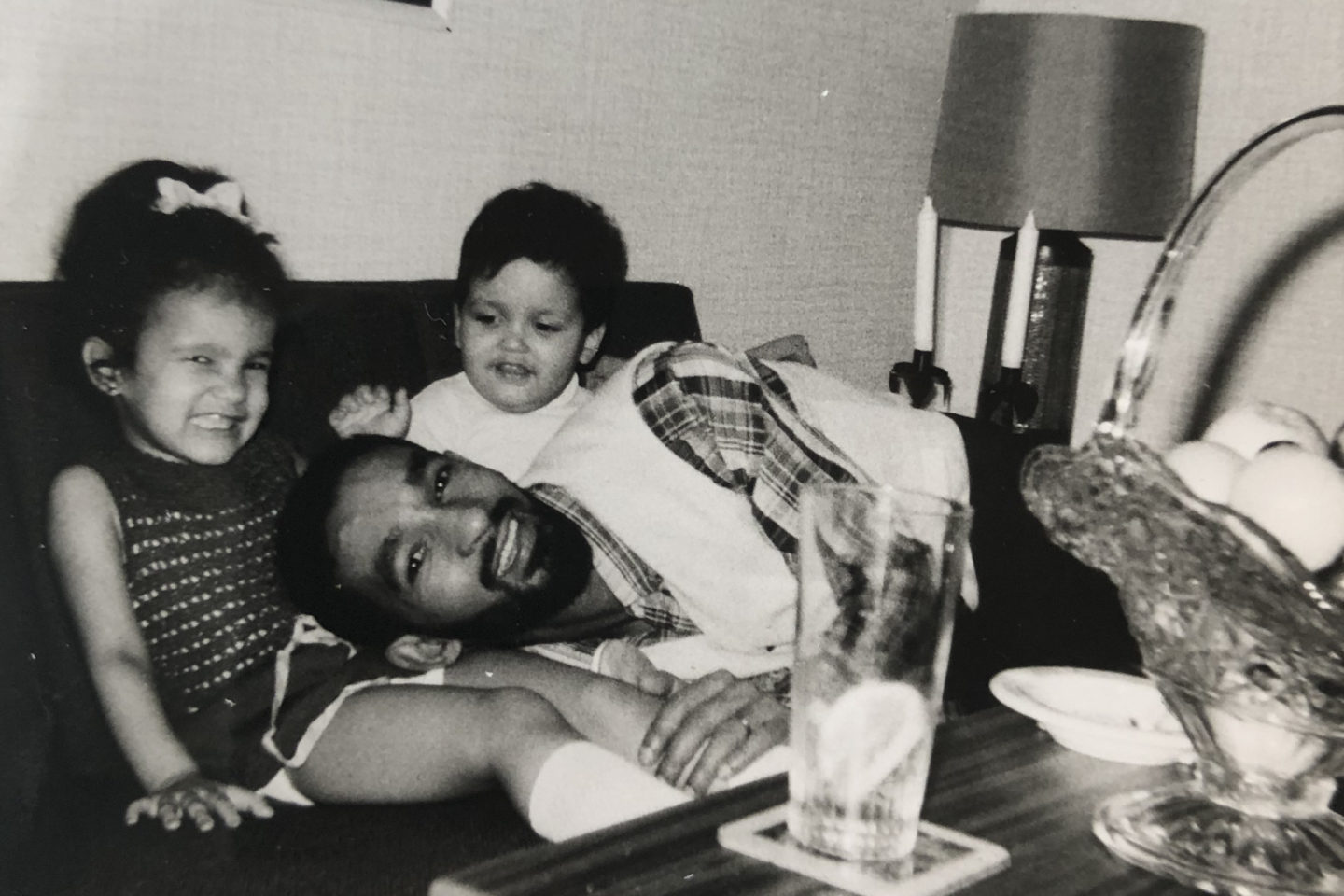

Bosch’s is a remarkable story of prevailing over adversity though, and there’s no doubt he’ll rise above his disappointment – it’s in his blood. More than 60 years ago, it was tribulation of a different and devastatingly far-reaching kind that his family were living through. That’s when Bosch’s grandfather Eddie Bosch bade a hasty farewell to his family in South Africa and fled into exile.

“My grandfather Joseph Edward Bosch was born in Genadendal outside Caledon in the Overberg. Due to the political inequalities that existed at the time, at the tender age of 17 he jumped a ship to England and then to Sweden under the protection of the United Nations.”

The Security Branch of the apartheid government had arrest warrants for all the men in the Bosch family. Bosch’s great-uncle Jonie Bosch was a freedom fighter in the Western Cape who was imprisoned, put under house arrest many times and tortured. He eventually died as a result in 1990.

Eddie lived in Sweden for 34 years, where he raised four children including Bosch’s father Brian. He lectured sociology at Gothenburg University after the Swedish Development Corporation funded his studies as part of a programme for those in political exile. Eddie remained actively involved in the struggle against apartheid, particularly in pushing for international trade embargoes and keeping the Swedish government informed of the situation in South Africa.

All this time he could have no contact with his family in South Africa, however, as the government intercepted any communication. “He never saw most of his family again.” When he did eventually return, his mother, father and most of his 11 siblings had died. Bosch’s great-aunt Iris is the only sibling still alive, said Bosch.

“During his 34 years in Sweden he was offered a Swedish passport multiple times, but he promised himself that the only passport he would accept again was his South African one. That was eventually reinstated in the early 1990s. My grandfather passed away in Cape Town in 2012.”

Noble, but costly

It was a deep desire to honour his grandfather and the country he cherished that led Bosch to switch allegiance, despite Sweden being a far more lucrative option once he had reached international level. Having been one of the top 10 snowboarders in the world as a junior, this was a massive decision.

“My family is very political. Every year from [when I was] a baby, I came to spend time in South Africa together with my grandfather and family. They talked human rights, politics and sociology. Even the years where I was obviously too young to understand, in retrospect it really had a great impact on me. The story of the people’s struggle against apartheid and that nothing is impossible has really inspired me. It’s something my grandfather has engraved into my heart.

“I want to honour my grandfather’s work and legacy, give back as much as I can to our people. I remember to this day, when South Africa was portrayed incorrectly in the Swedish media my grandfather used to get furious. So, representing South Africa is the least I can do while snowboarding professionally, because all great nations need a great ambassador outside the nation’s borders.”

While a noble decision, snowboarding is not a cheap sport. Without the backing of a wealthy federation like Sweden’s, Bosch has had to find his own funding. He has been part of a scholarship programme from the IOC’s development fund and works with several sponsors.

“It has been very challenging, especially in the beginning for my parents. But I have worked on my social platforms during all this time and since a couple of years back, I am able to live and train and compete and make ends meet with the income from that.”

A citizen of the world

Bosch switched allegiance officially in 2016. A former South African diplomat told Mandla Mandela, Nelson Mandela’s grandson, about Bosch and his desire to represent South Africa. “He was helpful with leading contacts with the sports minister and relevant departments and associations in order to register me as a South African winter sport professional athlete.”

Bosch has made his mark since then, proudly brandishing the South African flag on slopes around the world after qualifying the country for the World Cup circuit.

Growing up in Sweden and attending school in Norway, but with such strong connections to South Africa, it’s understandable that Bosch has sometimes struggled with his identity. But seeing the South African flag next to his name on competition start lists is still a thrill for the 25-year-old.

“It’s an amazing feeling that makes me really proud, because as a youngster I questioned my South African identity. My grandfather told me what defines me as a South African is not where I am born or even which passport I’m carrying. He reminded me that he lived without a passport for 34 years, but what defines you as a South African is what you are prepared to do for your nation and its people.

“In the past this was kind of a handicap because I was too young to understand that being different can really be a privilege if you understand and can accept it. I, like many children born in exile first, second or even third generation, would really understand these questions – where do I belong? Where do I come from? And what I have come to appreciate now years later is that I am a world citizen. I can quickly grasp and understand different cultures and can therefore feel at home very quickly regardless of where I am.

“With my SA identity I am very positive, regardless of the challenges I am up against, and am easy-going and friendly. With my Swedish identity, I am very organised and always on time.”

A goal of greatness

Bosch spends 10 months of the year travelling to train and compete, so he relishes the time he gets to spend in Africa.

“I love Afriski,” he said of Lesotho’s only ski resort, where he and his father help upcoming generations of athletes. “When I started out on my local hill in Sweden, it was maybe half the size of what Afriski offers. Of course if you’re chasing the professional career that I have, you would have to follow the snow like I do. That’s where I think I am going to be in a position in a couple of years’ time to help younger upcoming riders.”

Bosch’s long-term goal is to turn South Africa into a great winter sports nation, and then use that influence to promote and work for social equality and justice in the country and inspire others to strive for greatness.

But for now his personal quest for Olympic glory continues, and thanks to the December travel ban, Bosch has to wait another four years to fly the South African flag on the greatest stage of all. “What really upsets me is the very same discriminatory acts that my grandfather fought against are still happening to South Africans to this day. It’s definitely a hard hit for me, because this is something I’ve been working towards since I was 13 years old. But it also gives me a lot of fuel and motivation towards a medal at the Olympics in 2026.”

Eddie died before he could see his grandson represent the country he treasured and for which he fought so fervently, but Bosch has no doubt what his response might be: “He would give me that smile and be very proud, because he always knew.”