An intimate homage to Chinese migrant life in SA

A curated show at a former corner shop in Brixton, Johannesburg, offers a glimpse into the lives of a Chinese migrant couple who made apartheid South Africa home.

Author:

20 November 2020

Chappies gum as change, half loaves in flimsy plastic sleeves and an open pack of cigarettes to sell loosies (hidden from inspectors): this was the trade and livelihood for the woman behind the counter of the corner cafe.

It was also the only life Ho Kway Ping knew for the 56 years she ran the Caroline Supply Store at 166 Caroline Street in Brixton, Johannesburg. On average it closed two days a year, and the home at the back of the shop was where she raised her four children.

In 2018, aged 81, Kway Ping finally closed and sold the store. It was farewell to her corner cafe and the property that includes two adjoining shop fronts. For decades, these spaces were retired from trade. The Hongs had only opened them to follow old trading law restrictions for after-hours sales. Inspectors and their clunky bylaws were haunting spectres from the apartheid past. It is what made Kway Ping feel like a guest in the suburb in which she lived for over half a century.

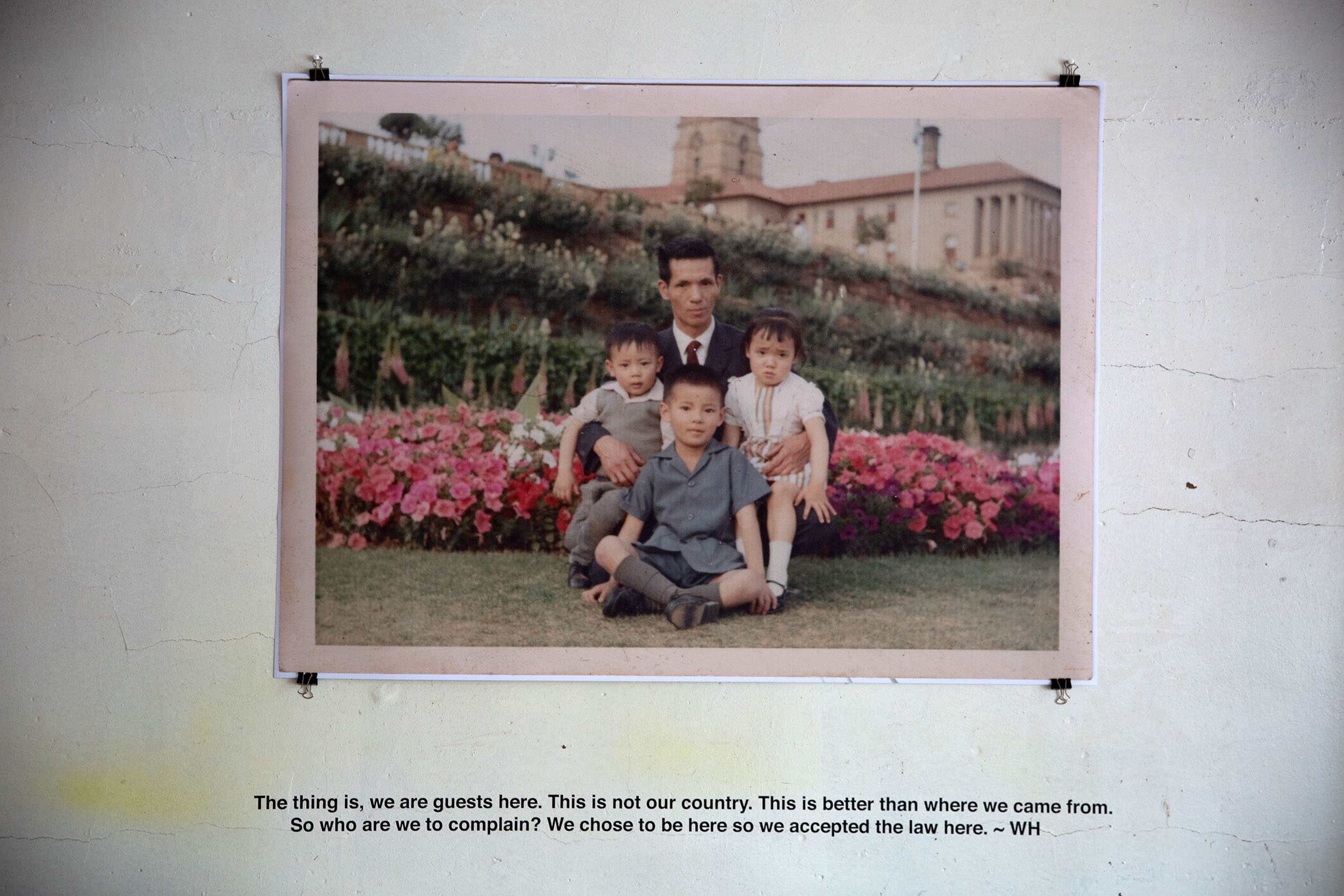

Brixton was a working-class area for whites only when she moved there in 1961 to join her husband, Ho Chee Hong. The couple could own the store only through a loophole: by finding an acquaintance, a white man named DJ Rousseau, who agreed to be their front on official documentation.

Living at the back of the shop was a way the couple could save money. It was also a way to stay invisible – being useful as shopkeepers to the community, but not sticking out as neighbours.

An exodus under harsh conditions

Kway Ping had left China via Macau in 1957 and spent a few years in Mozambique where some of her family members had settled after their exodus from China. The rise of the Chinese Communist Party from 1949 hit villagers, like Kway Ping’s family, hard. Tough working lives turned to misery as poverty, famine and civil strife deepened. The threat of being sent to labour camps and being put to death by party decree hung over everyone’s heads.

The life of a young migrant woman was easily decided – Kway Ping would be married to a Chinese man in South Africa. Matchmakers saw to the details.

Chee Hong was short in stature, so some people just called him Mr Shorty and his bride became Mrs Shorty, Kway Ping says in a mix of Cantonese and English. To others, they were “the Chinaman and his wife”. In the last few years, Kway Ping became magogo to her customers.

By 2018, Joburg’s corner cafes had long been rushed to obsolescence. For decades, mini malls with supermarket chains have served the needs of suburbs. Spaza shops and petrol station forecourt stores are the new era of convenience.

For Kway Ping, the backrooms of her corner shop finally grew too quiet. Her husband died in 2007. Her four children had grown to follow their own life paths – and even the last family pet, a myna bird rescued as a fledgling in 2004, died.

Packing up meant sorting through all she held on to for years – part frugality and part hoarding. Kway Ping hardly threw anything away. The back of cigarette cartons lived again as notepads for quick arithmetic, an old Oxo stock cube tin was the cafe’s cash register. Shop stock no one needed any more – shoelaces, press studs, retractable BIC pens – survived.

Ever self-sufficient and capable, she sorted out her affairs and left 166 Caroline Street for Cape Town just as quietly as she had arrived 56 years earlier.

Where real life happens

In the past two years, new owners and incarnations have been a fresh chapter for 166 Caroline Street. The back rooms were living quarters for migrants at one stage. In this era, it wasn’t migrants of Chinese descent but newcomers from Africa.

A city lingering under a legacy of segregationist spatial planning, turgid bureaucracy and lack of imagination still hasn’t come up with solutions for decent accommodation for those below the “low-income” bracket or for people who don’t have documentation to qualify for grants and subsidies.

Artist Tamzyn Botha, a Brixton local, sees this flux in a stressed suburb like Brixton as where real life happens. So she signed a lease for the shop front spaces, transforming them into Shade – her studio and gallery. Together with the back-yard tenants she grows vegetables, the way Kway Ping did for years.

“When I first got here I found old Chinese newspapers and pieces of paper with Chinese writing on it. Stuck behind the shelves were what looked like price lists,” says Botha of some of clues of the other life the space had before Shade came into being.

A year later, by serendipity and coincidence, Botha and Kway Ping’s lives would finally intersect.

A meeting point of memory

Kway Ping’s eldest son, Winston Hong, was in Joburg showing a visiting relative from the United States “what had happened to mom and dad’s old shop”. Botha and Hong began talking, and Botha’s interest in Kway Ping’s life deepened.

“I have moved 36 times in my life,” she says. “Ping, though, stayed in this one place for 56 years. Like her, I’m also a bit of a hoarder, a recycler and, I guess, a romantic, so I could understand why she held on to so much,” says Botha.

In Botha’s mind a project was forming: gathered stories could form a social record of the life of a Chinese family under apartheid. And she could draw it all together with contemporary artistic framing.

Over the next 18 months she started speaking to the four Hong children – none of whom live in Joburg anymore. And on a trip to Cape Town, she finally got to sit done with Kway Ping for a chat. Now 83, Kway Ping lives with her youngest son, Bruce, and his family, who translated for Botha.

Related article:

“We would chat, and Ping would tell me some things, then go and fetch something to show me that she had kept all these years,” says Botha.

Botha recognised the textured personal history emerging as intergenerational recounting turned timelines into lived realities. The everyday ephemera that survived were touchstones of a different time. Importantly for Botha, the woman at the heart of the story was ready for Botha’s spotlight to fall on her story.

Back in Joburg, Botha bounced ideas around with Sally Gaule, an academic, curator and fellow artist she had met by chance when their dogs hit it off in a Brixton park.

Together they conceptualised Behind That Window, turning 166 Caroline Street into a temporary exhibition. It is a homecoming for the objects Kway Ping and the Hong siblings have shared for the exhibition. Gaule and Botha have included objects and ephemera not just of the familiar trading life of the family but also unseen ones taken from the lives lived beyond the shop counter.

A repository of life

Kway Ping’s elegant engagement dress is on display. “I only wore that once,” she says in Cantonese, speaking from Cape Town about the extravagant garment. She never parted with it though, carefully replacing it in its original box and only looking for it again for Botha more than 50 years later.

There are the Hong siblings’ Chinese comic books, cassettes of the Chinese opera Kway Ping listened to to fill the silence and the makeshift box chair Chee Ho made that she sat on between serving customers. There is also the original receipt from the sale of the shop. It is dated November 1959, and the name on top is “Rousseau”, a stand-in for “Hong”.

The artists write in the exhibition text: “The place of exhibition is important because it’s prosaic, ubiquitous and familiar to South Africans … the power of the space is writ large: the marks of wear and tear can be read metaphorically as analogies of other injuries.”

Gaule says: “We agonised a lot over how as outsiders we were going to do justice to their story. It was wonderful that this family that we were total strangers to was willing to trust us with and, in the end, we let their words tell the story.”

She adds: “The corner cafes were spaces of trade, constants in the neighbourhood. People who were prohibited from interacting across the colour bar could actually have some connection in these spaces.”

A treasure trove of memories

The exhibition is told mostly through the quotes from the interviews with the four Hong children, Winston, Yvonne, Vernon and Bruce. Vernon, who arrived from Cape Town for the launch, had said his goodbyes to the store many years ago. But still the memories flooded back.

“I keep remembering things now … we played under the counters in the winter because it was sunny there.” He points out hiding places in the shop.

Bruce says: “It took Tamzyn’s and Sally’s fresh eyes to see our story in the way they have. It was sincere curiosity, not nosy inquisitiveness. It’s good that people can see, so they understand what life was like behind the shop counter.”

For Winston, the eldest, there is a mixture of pride and old embarrassment. “I used to tell my teachers to drop me off in Chinatown, not at the shop because I didn’t want them to know … where I lived. But mom and dad got us all through college and varsity from working at the shop.”

The sister in the mix is Yvonne (now D’Aberton), living in Brisbane, Australia with her husband and daughter. She says growing up in the shop was “tedious at best” but also that “in the mundane lies a treasure trove of memories. Living in Brixton, we were part of the scenery and yet, to a large extent, we were removed from it. We interacted with people every day but never went into their homes.”

Related article:

It was the expected divide along racial lines in South Africa under the Group Areas Act, says author and Chinese South African history researcher Dianne Leong Man. Leong Man, who spoke at the launch of the exhibition, says the generation of Chinese shopkeepers were industrious and undeterred. They had to make a go of it, having made the impossible journeys to South Africa as stowaways and being forced to buy immigration identities. They became so-called paper sons and daughters to fake their way to a new life in South Africa.

“Many Chinese shopkeepers lived in cramped quarters with their families behind their shops, like the Hongs. They sold everyday necessities in small quantities and gave credit to their customers.

“The value of this exhibition is for the younger generations to know that we are the products of a lot of hardship and dedication,” she says.

For Gaule and Botha, the exhibition presses pause just long enough to give a glimpse into the everyday life of one migrant family. It is a tale of a journey from China to South Africa, of being invisible but enmeshed in a neighbourhood, of the burden of running a viable corner shop and of being different but needing to belong.

Ultimately, it is also about unexpected connections, the alchemy of coincidences and the corner shop that has stood to witness it all.

Beyond That Window is on until 29 November 2020, Wednesdays to Sundays between 11am and 4pm, at Shade, 166 Caroline Street, Brixton.

Memories and comments from Ho Kway Ping were shared in Cantonese with the journalist and retold here in English.