Album Review | Playing on our musical heritage

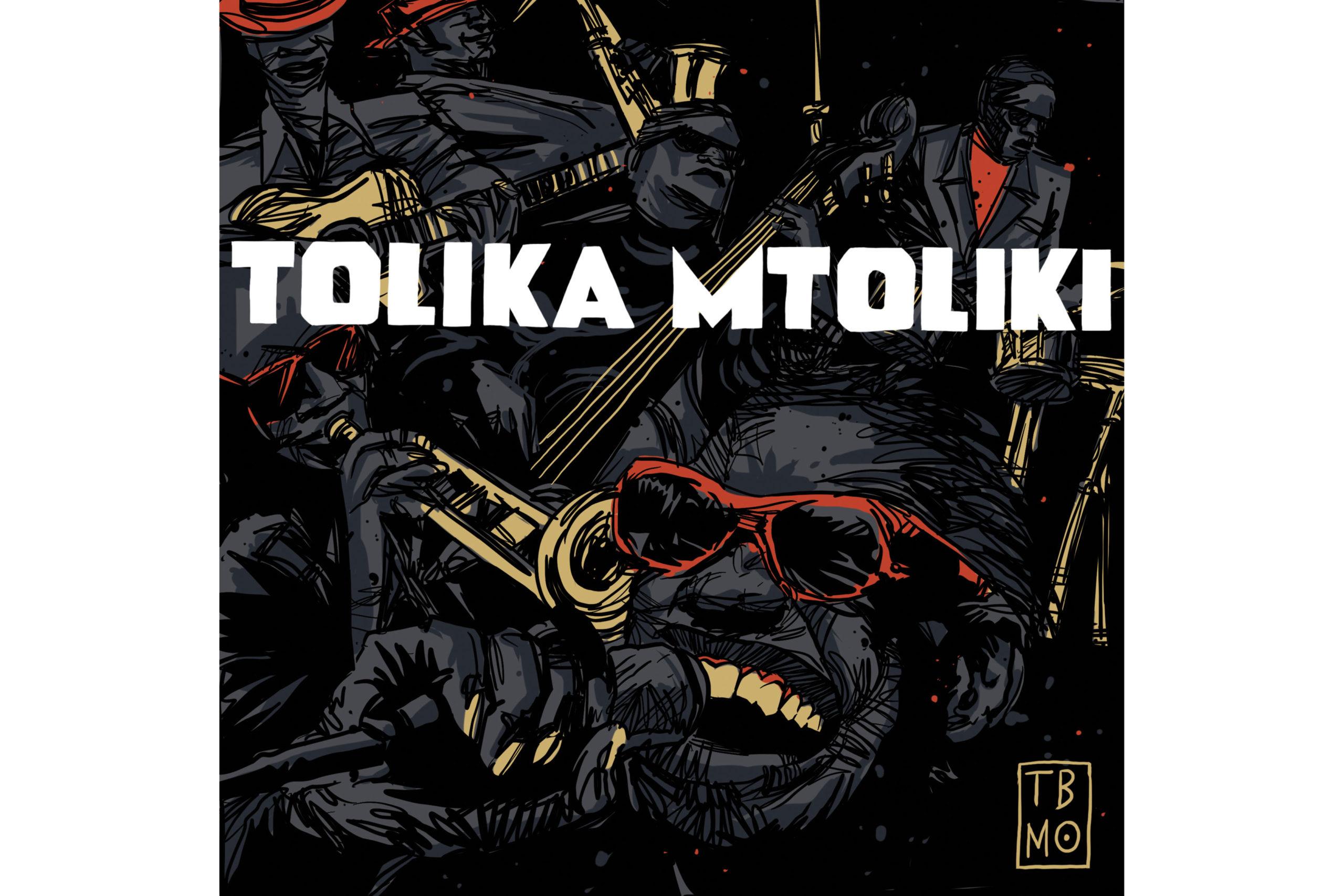

The Brother Moves On has created a ‘time capsule in vinyl’ with its latest album, which pays homage to South African jazz greats both new and old while capturing the spirit of an era.

Author:

12 October 2021

“It was made for that time,” says Siya Mthembu, vocalist with The Brother Moves On.

He’s discussing the track You Think You Know Me, released in mid-July, as trucks and shopping malls burned in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. The album from which the track is drawn, Tolika Mtoliki (Interpret, interpreter), arrives on 25 October – but the early drop for that track was a direct response to events.

Mthembu was on day 12 of his encounter with Covid-19, confined to his home, thinking, “This is happening – but nobody’s saying anything about it.” Almost simultaneously, Matsuli Music label boss Matt Temple sent him a message: wasn’t it time for that track? “We’d been thinking about a release in 14 days,” says Mthembu, “but now it was, No! Make it happen in 72 hours.”

You Think You Know Me riffs on Blue Notes trumpeter Mongezi Feza’s iconic anthem You Think You Know Me (But You’re Never Gonna Know Me). It opens with verses itemising corrosive ethical betrayals, including cultural betrayals (“you place Enoch Sontonga’s prayer next to Die Stem / a Nazi war crime next to a prayer”), political (both the “after sex niece raping shower domkop [idiot]” and “it’s a new dawn … can I put a new dawn on these ashy, bloody Marikana hands?”), and practical (“Eskom shedding the load of townships still paying for Black hardship”). Finally, while the elite commentariat have filled media pages labelling July 2021 everything from “riots” to “counter revolution”, the track segues into Feza’s wordless melody after a bitter, closing, “You think you fucking know me – that’s the problem.”

For those who heard the track in that July week, the impact was searing. But the cumulative iteration of betrayals was not assembled opportunistically at the time. It came from a conversation between Mthembu and his mother, Thobeka, long before. “I was sitting on a bench in the yard, she was sweeping. We were talking politics, about things that had happened – impromptu poetry of all the frustrations of the time.” Thobeka Mthembu’s role as co-lyricist is credited, but her son says she is less happy about the credit now because of that final profanity, which was not hers.

The tune, of course, is older, composed by Feza in the early 1970s. Particularly, but not exclusively, for those who grew up in Africanist political traditions, “it’s our real national anthem,” says Mthembu. “You heard it as a kid. Before you even knew what politics was, you ended up singing it to yourself.”

Shared rebirths

It was You Think You Know Me that brought saxophonist Muhammad Dawjee, the band’s newest alumnus, into this recording. Dawjee had been working with Mthembu and other members – bassist Ayanda Zalekile, guitarist Zelizwe Mthembu and drummer Simphiwe Thabalala – intermittently since they shared a stage at a 2018 Wits performance, but, “I forced my way into this album. That song’s been in my consciousness for such a long time that I just really wanted to play it. ‘I’ll even do it for free,’ I told them,” Dawjee says.

A shared desire to resurface a musical heritage, rather than the content of any one song, underpins the album, which they call “a time capsule in vinyl” with homages to the work of Moses Molelekwa, the Malopoets, Johnny Dyani, Batsumi and Philip Tabane. The Brother Moves On has performed at London’s Church of Sound and Johannesburg’s Orbit exploring the music of Batsumi and Malombo. At a house party, Temple heard them play and broached the idea of the project. “But in fact,” says Mthembu, “I’d sent an email to Matt a decade ago suggesting something on legacy and heritage music. I didn’t realise I’d had this idea before.”

The idea of cyclical musical rebirths and, in Mthembu’s words, “going back to go forward … how the beautiful ones are not yet born today, but may have been born before” is made explicit in the tribute For Mo, which refers to Molelekwa. The track opens with a recording of the jazz pianist describing his research on where music comes from: “It’s not in one lifetime that one becomes a musician.” Mthembu’s vocals reflect these ideas. Stylistically, the sound palette alludes to influences the pianist cherished – from the rest of Africa and the natural world – before the guitar draws out the melody of Bo Molelekwa: we’re Moses’ people.

“Moses’ song,” says Mthembu, “wasn’t something you’d expect The Brother Moves On to play. But like all the songs it spoke to something very personal in us. Often we found we could only articulate what that was after we had worked through the music together.”

Francis Gooding’s liner notes for the album foreground the band’s declaration that “these are not cover versions”. That idea has two aspects. Mthembu points out that in jazz “playing a standard is never a cover,” and Dawjee expands on that. “Jazz relates to ancestry through a canon,” the saxophonist says. “These songs are a canon that expresses the spirit of a place and of a people, and the thrust of an era – the literature of our music. As an improviser, that’s where I find my inspiration.”

The other aspect is political. “Talking about covers speaks to the idea of ‘ownership’ of a song,” says Mthembu. “I heard so many cover versions at home that often I didn’t know whose song it was and the intention of those covers was often beautiful. But without undermining the important rights of Black creators, songs like these really do belong to the people. Now, everybody’s selling off their copyrights [to global corporations] for cash.”

We have been here before. Those sales put musicians in the same position as Black artists under apartheid, paid by a label for total ownership of their songs. The sums involved may be bigger, but the loss of control over what is subsequently done to the music and who profits is exactly the same.

Collaborative collective

Although Tolika Mtoliki distils ideas that were floating around the band for a long time, Mthembu feels their “collective culmination made it better … took us out of the core [The Brother Moves On] four, and back to the old collaborative collective thing”.

Dawjee felt it too. He cites the Malopoets’ Madoda. “I was invited to participate vocally, which hasn’t really happened before. There were five or six of us around the mic: teaching the lyric and what it meant because not everybody knew the language, choosing harmonies. Working together on the song allowed us to find our own space.”

Working with the band in a more liminal musical arena has also affected Dawjee’s instrumental expression. “Siya invited me to a jam session. It wasn’t jazz – nobody’s calling tunes. And being put in that position made me remember all those ways of making music I’ve grown unaware of because of becoming a sax player. I used to play bass, jamming with a couple of Afrikaans guys in a garage. Now I’m holding a sax, so how do I use that to bring that kind of feeling and energy?”

Related article:

Recording at saxophonist Steve Dyer’s Dyertribe studio brought jazz collaborators. Mthunzi Mvubu plays sax and flute. “He brought fresh air to Batsumi’s Anishilabi,” says Mthembu, and “[pianist] Bokani Dyer was there, saying, ‘Guys, I’m on the farm anyway, just let me get some breakfast and then please tell me what to do.’” Bassist Ariel Zamonsky pops up on Madoda, where Steve Dyer adds another guitar.

Given all the jazz participation, is The Brother Moves On now thinking of itself as a jazz band? “Well,” says Mthembu, “we were all raised on jazz. Obviously, it’s a part of us … but we’re still working on other music. We’ve got a project that sounds very different coming out early next year.”Before that, there’s a national tour for Tolika Mtoliki kicking off on 21 October in Pretoria. The tour includes community spaces such as Wolf & Co in Tsakane and township spots such as H&H Jam in Soweto. “Playing the townships is vital to us,” says the band’s tour proposal, to ensure “our message meets the streets”. And genre is largely irrelevant: purpose matters more. “Three or four years ago we got over the idea of being a band that’ll make commercial music,” says Mthembu. “I think Steve Dyer got us most right when he called us ‘one of the last protest bands’.”