Against the ropes, Sisonke Boxing Club fights on

Despite little recognition of its value to the young fighters who use it to stay off the mean streets outside, this small academy is punching way above its weight.

Author:

27 September 2021

Even with the odds weighed heavily in favour of dashed hopes and faded dreams, a boxing club run from a small, rundown room no bigger than a few square metres is producing champion fighters.

There’s little to no ventilation in the makeshift training gym that houses Sisonke Boxing Club in Hout Bay, Cape Town, but below the flickering fluorescent lights burns an incandescent love for boxing. The room belongs to the Sijonga-Phambili Adult Learning Centre, which sits on the border between Imizamo Yethu, a shack settlement also known as Mandela Park, and the affluent suburb of Penzance Estate.

The club is more than a school of boxing – it’s a school of life, a refuge and a way to survive the harsh lessons waiting to be dished out by bullies and drug abusers on the streets of this densely populated community. The area is home to roughly 50 000 people who live at the mercy of landlords, slumlords and the Cape Town city council. The residents regularly express their frustration with crime and the lack of basic municipal services and housing.

At the heart of the Sisonke Boxing Club is Bongile Centane, 53, the soft-spoken and quietly strong coach, and Jonny Cohen, also 53, the benevolent manager and boxing enthusiast.

Centane is a former boxer who, like many promising pugilists from all over the country, never went professional for reasons all too familiar in the blighted history of the sport’s South African narrative. He works as a petrol attendant at a local filling station by day.

“I was born in the Eastern Cape, in a place called Mamolweni in Presley Bay. I started boxing when I moved to Mthatha at the age of 14 or 15, in Ngangelizwe township. In 1991, I moved from there to East London. One of my friends liked boxing and I used to fight with him in Mthatha,” Centane says.

“When I finished my matric, I moved to Cape Town to live with my brother who was living here. In 1997, I decided to open the boxing gym here in Imizamo Yethu. Back then there were no houses; there were only tin shacks.”

A hard bargain

Sadly, Centane’s boxing career didn’t stretch as far as his love for the sport, but in coaching he has built his reputation as a man who produces competitive young boxers. He’s a hard taskmaster, not afraid to raise his voice when he spots a petulant attitude or a lazy technique. He demands the best out of every boxer, the young ones included. And though some of them find the going tough, Centane prefers them all to be with him in the gym, rather than playing in the streets and potentially being in harm’s way.

“I like to look after the kids. I don’t want them to go to the smokkel house [shebeen] because it’s dangerous for them. You have to look after yourself here. That’s why I love boxing – I take the kids away from the streets,” he says.

Centane’s shift at the filling station starts at 6am. He’s awake at 5am to get in a bit of exercise before work, where he serves each customer with a gentle smile. It’s a job he’s been doing for years and with great pride. Though it’s probably a life far removed from the one that escaped him, boxing has offered him more in exchange for his talent.

In another world, Centane would have been rewarded for his devotion to boxing. The multimillion-dollar purses on offer in the global boxing arena seem far removed from the amateur ranks that barely exist on the fringes in South Africa. Men like Centane, who have given their lives to nurturing the sport’s future champions, should be able to live a more comfortable life with boxing.

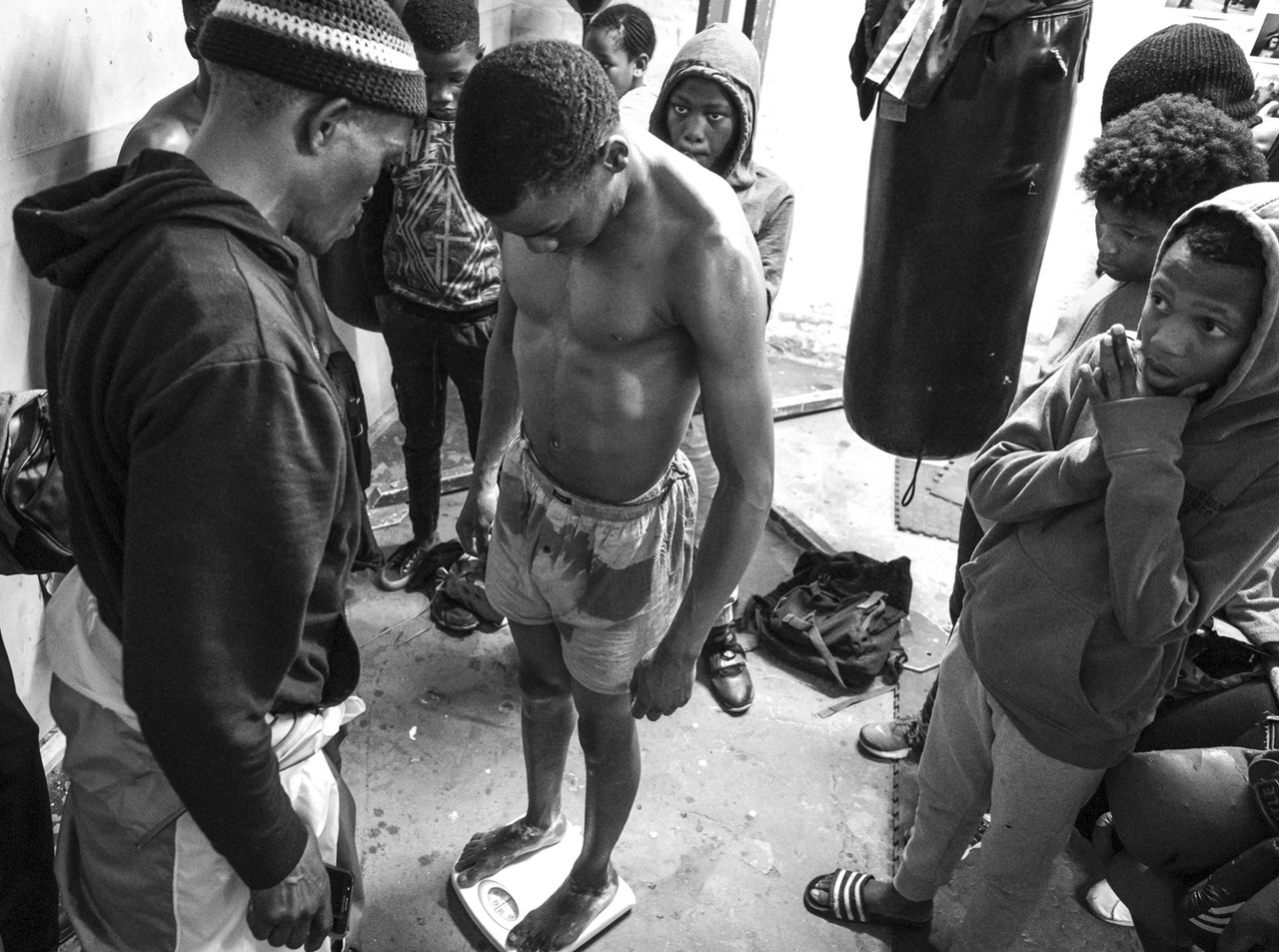

Centane knocks off work at 4pm. There’s a spring in his step as he strides uphill towards the centre where he gets to live out his passion for boxing from 5pm until 7pm. That is his routine five times a week. But the club is suffocating under the cramped space in which it is forced to operate. The training area is smaller than a boxing ring, and when 20 or more aspiring boxers of all ages are crammed inside there’s barely room to breathe, let alone swing a punch.

A new coat of paint on the walls is long overdue. Instead they’re draped in boxing posters and photographs of the gym’s finest products – young boxers who have gone on to win tournaments and national championships. They represent Centane’s proudest moments as a coach and father figure to these kids from Imizamo Yethu, who start when they’re as young as five years old.

“The difficulty we face here is gangsterism,” Centane says. “We take these kids away from the gangsters on the street. That’s difficult, because it’s easy for them to influence the kids. The children like sport so they come to the boxing, but we don’t have gloves so we have to get sponsors who help us out with gloves.”

Backing a buddy

One of these sponsors and friends is Jonny Cohen, a businessperson and filmmaker who has helped Sisonke Boxing Club keep its doors open for a number of years. “About six years ago I met Bongi, who was working at the BP as a petrol jockey, and just in conversation realised we both loved boxing.

“Bongi invited me to come to the gym, and I realised I could get involved and play a role in supporting his vision and his dream and add some value. The first thing I did was buy all the kids their own gum guard, because they were just sharing one gum guard between them.”

Cohen and Centane found common ground in their love for boxing. Eventually they struck up a friendship that would lead Cohen to form a tight bond with the club and its trainees for more than seven years now.

As Cohen speaks, a 10-year-old boy walks behind him, taps Cohen on the back and says “John Vuli Gate!”, after the song and dance craze. Cohen chuckles quietly and smiles to himself.

“I grew up with boxing. I had a father who was very interested in it. I boxed a bit but what attracted me to it was, growing up in apartheid South Africa, my first experience of what I can describe as non-racialism was boxing,” Cohen explains.

“Going to boxing fights, the boxing community was very integrated. That was my first experience of it. I think in that way boxing has potential to be a great unifier and leveller. So I’ve always enjoyed and stayed connected to boxing somehow.”

Disdain for dreams

The administration of boxing in South Africa over the past 20 years has left a trail of regrets and unfulfilled promises. South Africa was not able to send one boxer to the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo this year, after failing to pay registration fees in time for the African qualifiers in Senegal. Amateur boxers must qualify in their respective regions or zones to represent their country at the Games.

“I think there’s a greater challenge for boxing in South Africa, and in particular Sanabo [South African National Boxing Organisation] really needs to have a look at itself, because South Africa was the only country in the whole of Africa that didn’t participate in the All Africa Games, and it’s at the All Africa Games where they selected the competitors to go to the Olympic Games,” says Cohen.

“So with all our unbelievable boxing talent in South Africa, and so many boxing gyms across the country, the fact that we didn’t have one representative at the Olympic Games is sad, but it also points to a really good opportunity for us to fix it and get it right.”

The amateur boxing fraternity has been on the ropes for some time now. Year after year, talented boxers are left to wash up on the sidelines of society to fend for themselves. Boxing as a safety blanket doesn’t insulate them from the rigours of life.

Fighters require balanced nutrition to manage high-performance physical conditioning, and a healthy lifestyle to stay in peak physical shape. Those habits are almost impossible to create by athletes living on the edge of society, where more basic necessities are conspicuously absent.

A new executive that came into office in June has promised change, as every administration has done.

Elusive recognition

But change is too late for Centane, who faces an uncertain future. His home, a wood and tin shack, is scheduled to be demolished by his landlord, a taxi owner. Despite working a full day and volunteering his coaching time, he struggles to keep a roof over his head.

“The landlord wants to build flats there. They want more people to rent and get more money, so they told me I have to get another place. It’s difficult for me,” says Centane.

If only boxing was kinder to Centane, he could have enjoyed a measure of success that would see him live a more comfortable life. Recognition of his influence on boxing in local circles and his selfless commitment to the sport would have provided Centane with a life more secure.

“In 2004, one of my boxers won a gold medal in Pretoria at the national championships. They asked me to go with him to represent the Western Cape. Another boxer of mine won the bronze medal. In 2015, one of my girl boxers won silver at the national champs in the Free State. I’m very proud of her because there are so few ladies in boxing.

“I had a 14-year-old boxer who won a bronze medal, which was nice. I have three professionals here. My nephew is a promising boxer. He’s going to be a champion. Even Xolisa Matane is a promising boxer.”

For young boxers like Matane, who has been boxing for six years, the gym is a life commitment. He is on a path that he hopes will bring more glory and recognition to the Sisonke Boxing Club.

“Boxing has changed my life,” says Matane. “I always stay positive and think out of the box, to stay in the community and hustle. If it wasn’t for boxing I would have gone down a different path. I think I would have been like one of the guys in Mandela Park, not knowing what to do.

“For me, coach Bongile is like a father for all of us as boxers, because he teaches us respect and how to behave ourselves inside and outside the gym. My dream is to become a world champion boxer and make coach Bongile proud. If I can achieve that dream, it would mean a lot to me. Coach Bongile is inspiring us to achieve our dreams.”

More than a sport

Sacrifices will be required for Matane along the way. Although the rewards are not always guaranteed in monetary terms in the South African context, the rewards for vulnerable youths may mean far more than that.

“Boxing is one of the most artistic sports. You become full of imagination and when you train your mind feels more fresh and active, and you always feel positive about life,” Matane says.

Centane is hoping that, at the very least, all his young boxers are equipped to handle a cruel world that seems ever willing to harm children. “Boxing is good for the children because of self-defence. If someone is attacking you, you can’t just stand there, you can punch them and run. If someone wants to rob you, you can punch them and run,” he says.

“Boxing makes you strong, it makes you think. If you want to be a good boxer, you must have discipline first, look after yourself. Don’t move around, stay at your house, especially these days with Covid.”

The future of Sisonke Boxing Club is uncertain. It’s on borrowed time and exists at the mercy of the Department of Higher Education, which owns the adult learning centre. Cohen has spent years pleading with the City of Cape Town to create a safe space for the boxing gym, but with little success.

“The biggest challenge is finding a venue. The beauty of boxing is that you need such a small space to make such an impact, yet the City doesn’t really recognise that potential,” he says. “It’s sad and frustrating that the leadership don’t actually recognise something so simple, where we have said, ‘Listen, let’s create a private-public partnership. Give us a piece of land and I’ll make sure the money is there to build a gym space that benefits everybody.’

“Bongile is everything. He is the heart and soul of the club. It’s a real labour of love. This guy works at a petrol station from six o’clock in the morning until four o’clock, walks here, and then trains kids from 5pm to 7pm, goes home and repeats that five days a week – and he doesn’t get paid.”

Can’t give up

For Centane, boxing is too much a part of him to ever stop now. The sport has shown the potential to unite people from diverse backgrounds and build stronger, healthier communities.

“My dream for this club is to get a nice gym, because maybe one day they’re going to chase us away here. They might turn this building into a school and that will be a problem for us. If we get a new gym things will be all right. One day we’ll get a new gym,” Centane says.

“The government is always supporting soccer. They should support boxing. It’s so difficult being in boxing. They say soccer is nice because it’s not a blood sport. But I say there is so much sport and there is talent for everything. We like different things.”

Cohen emphasises the impact boxing is having on young women in the community. More and more young girls and women are finding that the sport offers a way to steel themselves against potential danger.

“We’ve seen an incredible amount of interest from young women to come and box, and that’s in the last year that it’s really grown. That’s very positive. I think young women get as much, if not more, from boxing than the guys.

“[Our] ultimate long-term vision is if we could somehow produce an Olympic contender from this small community and township. I think that would set an amazing example to people from very humble backgrounds that anything is possible.”