Afghanistan, a highway of history

In Text Messages this week, historian Arnold J Toynbee’s emphasis on the South-West Asian country as ‘a key-point in the structure of empires’ is poignant as the world abandons it.

Author:

29 July 2021

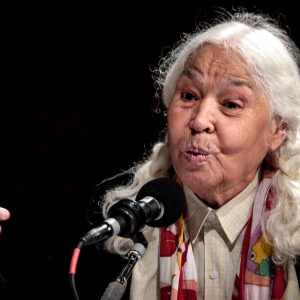

It is one of the most famous images of the late 20th century, though not without controversy. Staring startlingly wide-eyed at the camera is a young girl of 12, features set in an indeterminable way. Yet, the longer you look, the more you get the sense that her gaze falls somewhere between surprise and defiance.

A thousand observers will yield a thousand responses to and descriptions of the girl’s unwavering green eyes. She looked out from the cover of National Geographic magazine in June 1985, at a global audience, the photograph the work of photojournalist Steve McCurry. His subject’s name was not known, though, until 17 years later: a ripe enough comment on the practices – or, as some will say, the difficulties – of photojournalism. The moment, the shot is all; often the subject remains anonymous, a subject objectified.

In 2002 the “Afghan girl”, as she had hitherto been labelled (sometimes “The girl with green eyes”), was named as Sharbat Gula, a Pashtun who at the time of the photograph was living as a refugee in Pakistan having fled the Soviet invasion of her Afghan homeland. Jump a decade-and-a-half, to 2017, and life finds Gula married and being presented with an enormous – 3 000m² – home of her own in Kabul, the Afghan capital.

There the trail runs out, but the Taliban invasion of Afghanistan that is taking place as you read this will likely see all the country’s major cities fall, Kabul probably last. What will happen to Gula, already under fire in 1985 for “allowing” herself to be photographed with face uncovered? Authoritarian regimes enjoy making examples of significant and prominent people. While Gula arguably is better known outside her native land than within, she is sufficiently known, and certainly notorious by Taliban standards, to warrant attention.

Related article:

Afghanistan, like Poland, has been repeatedly invaded because of its strategic placement on so many crossroads. Poland divides western and eastern Europe, the European and the Slavic. Afghanistan sits between Central Asia and South Asia, beneath Russian republics, encircled by Iran and Pakistan and perpetually embattled.

The Achaemenid dynasty of Persian conquerors was here in the sixth century BCE and after. Then came Alexander the Great, having fought his way across the razor-toothed mountains of the Hindu Kush. The Indian Emperor Ashoka set up an inscription in Greek and Aramaic, the language brought by the Persians, at Qandahar in the third century BCE.

Buddhism made its way from India to the whole of Southeast Asia on a highway that ran through Afghanistan. Muslim invaders came from Bactria, Afghanistan their thoroughfare along which Islam came to India.

Strategic asset

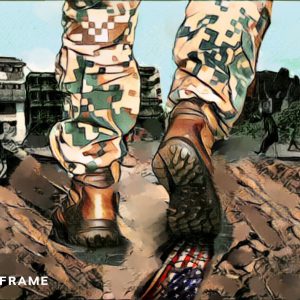

In one of those moments of eerie coincidence, my rereading of English historian Arnold J Toynbee’s classic travelogue Between Oxus and Jumna (Oxford University Press, 1961) began just as the United States stealthily abandoned Bagram airbase and fled the coming Taliban onslaught. To gauge what the world is losing in forsaking Afghanistan, one can do no better than quote from Toynbee.

In his opening chapter, “The Old World’s Eastern Roundabout”, he emphasises that the country is a classical example of a “roundabout”: “Afghanistan has been the link between South-West Asia, the Indo-Pakistani Sub-continent, Central Asia and eastern Asia.”

Writing about the intense rivalry for influence in Afghanistan between the US and the Soviet Union in the 1950s, which manifested itself in massive road-building projects, he writes: “These new roads promise to reinstate Afghanistan in her traditional position in the World… The bonus is valuable, but the accompanying risk is high. Roundabouts are strategic as well as economic assets, and strategic assets are tempting political prizes.

Related article:

“It will be obvious that Afghanistan is intensely interesting today for a student of contemporary international affairs. It is of equal interest for a student of the history of civilisation in the Old World during the last five thousand years. As he follows the main threads of history – economic, political, demographic, artistic, religious – he finds his attention being drawn again and again to the Old World’s eastern roundabout, as well as to its western one [Rome]. Afghanistan has been a highway for migrating peoples and for expanding civilisations and religions, and it has been a key-point in the structure of empires.”

Towards the end of the chapter he notes, with poignance: “The route through Afghanistan, circuitous though this was, was the earliest route along which India and China made contact with each other. This was the route followed in the transmission of Buddhism; and that is the most important transaction that has ever taken place between India and China so far.”

Weep, then, for Afghanistan, the Old World’s eastern roundabout deserted by today’s World despite its immeasurable contribution to its cultures, religions and humanness.