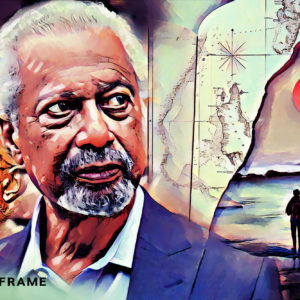

Abdulrazak Gurnah’s search for home

In the Nobel Prize-winning writer’s novels, migration is a process in which ordinary people are caught between the memory of violence past and present. For some, healing is possible.

Author:

27 October 2021

On the night of 11 January 1964, one month after Zanzibar gained independence, the Arab sultan and his elected constitutional government were overthrown by forces claiming to represent the African racial majority. There were reprisals and pogroms against Arabs and South Asians, resulting in the death of around 20 000 people.

Zanzibar’s much vaunted cosmopolitanism came face to face with the repressed memory of slavery and the slave trade. It had been one of the main slave trading ports and in the 19th century about 50 000 slaves passed through the slave markets here. The new rhetoric pitted the African against the Arab.

Related article:

Abdulrazzak Gurnah, of Arab heritage, fled Zanzibar in 1967 to England along with his brother, to land in the middle of racial hatred in a country coming to terms with imperial decline and its increasing irrelevance. In 1968, Enoch Powell was to make his infamous rivers of blood speech as he predicted a violent and sanguinary future for Britain with what he and other conservatives saw as a rising flood of immigrants.

Gurnah’s oeuvre reflects these histories of the Indian Ocean world, colonialism, migration, violence and race. What does it mean to belong somewhere, and does the migrant live a life that can only be about coping, with a persistent memory of violence past and present?

Migration as a process

In Gurnah’s novels, migration is not a single act. It is an ongoing process with individuals constantly caught between worlds, bearing the scars of former degradation and continuing secrets. It is a state of suspended animation, and as Hannah in The Last Gift, lashes out at her mother, why do these “vile, immigrant tragedies” continue to haunt people? These are ordinary people without tremendous psychic resources, who muddle through and there is the promise of redemption that lies in suggestions of a life beyond the space of the novel. Gurnah leaves open windows in each of his novels suggesting possibilities of healing through return, new meetings and possible resolutions. However, return too is fraught with the possibility of disillusionment as much as a sense of not fitting in.

In Gurnah’s Admiring Silence as much as By the Sea what the returning migrant is confronted by is a sense of unbridgeable distance, born as much out of estrangement as the guilt of leaving. In the former novel, the presence of persistently blocked toilets becomes a metaphor for the stagnation as much as the squalor of the postcolony. The central character in Admiring Silence lies to his white partner about his country and himself to win for himself a sense of self-esteem as much as to solicit affinity. It is his way of managing and of coping.

Related article:

There is no bedrock here, no haven from the heartless world. Families are fragile entities and consist as much of inner tensions as the fact that one belongs to them contingently. One may be taken in as a foundling, and subject to an authoritarian patriarch. On the other hand, as Gurnah says, “even love can be crushing”, as families make demands on individuals; fierce chains of required loyalty or obedience bind one. Menace attends every moment, and the child is the prime candidate for prospective violence. So too the young women, who are manipulated and begin to acquire a mere “mercantile worth”.

In Departure, the childhood of the protagonist is short and brutal. In Dottie, the eponymous character “comes through” but her siblings do not. Yusuf in Paradise survives, but luck matters as much as individual resilience or resourcefulness. There is none of the sentimentality associated with bourgeois fiction of the family as a unit which despite all its problems provides a space of return. There is no there there, as Gertrude Stein might have said, in Gurnah’s world of immigrants.

Colonialism’s lasting impact

The Indian Ocean world impinges on the consciousness of characters in which being Muslim is less about religion and more about a cultural cosmopolis – the world of Arabian Nights and tales of the trickster Abu Nawas. It is a world that takes in Palestine, the Swahili coast from Somalia to Mozambique, and Aden, Kerala and Bombay. Madagascar, an African island, seems to belong to another planet in this world determined by monsoon winds and historical networks. The Indian Ocean is both vast as well as familiar in its micro-worlds. Colonialism impacts on this world and creates new hierarchies and disruptions.

In Afterlives, we get a parable from a German colony in southern Africa during World War I. We know by now that colonial wars involved the large-scale carnage of colonial troops from Africa and Asia and mawkish European invocations of Ypres and Flanders usually forget this fact. An oberleutnant develops an affinity for Hamza, his orderly, and tries to civilise him through cultivating a love for Friedrich Schiller’s poetry. This misguided humanism is rooted in the hardness of racial difference and the impossibility of friendship between unequals. As Gurnah shows, the ideological mindset of superiority can only exude condescension, not affinity.

Related article:

Abbas in The Last Gift has the sense of coming from a tiny place, he remains frightened of the world with its vastness. This sense of men from small places trying to find a home in the world is a theme that runs through Gurnah’s novels. However, despite the scars, the memories of violence and the fragility of relations, they come through in the end.

This article was first published by Indian Express.