A steady ticking towards the hour of the hangman

The xenophobic and violent Operation Dudula is part of a global trend of rising right-wing vigilantism that is finding favour in an era of crisis.

Author:

5 May 2022

Since its first appearance in Soweto in 2021, Operation Dudula, which means to “push out”, has gained a reputation for inciting xenophobic sentiments and harassing people its members claim are undocumented migrants and criminals.

Its military camouflage-wearing leader, Nhlanhla “Lux” Dlamini, claims that the organisation is not a hate group and merely represents ordinary citizens who are standing up to gangs and drug merchants. In reality, all its street “operations” have been accompanied by violence, extortion and blood-curdling rhetoric.

This movement has emerged at a time of intensified xenophobia in South Africa. The hardline stances of political parties like ActionSA and the Patriotic Alliance, and street violence by so-called Umkhonto we Sizwe military veterans in KwaZulu-Natal, have helped create a social climate in which atrocities like the murder of Mbodazwe Banajo “Elvis” Nyathi in Diepsloot in April happen.

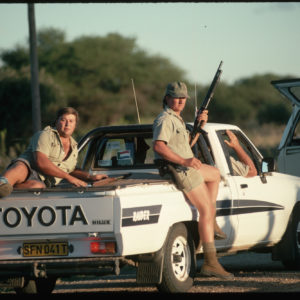

Operation Dudula seems to mark a disturbing new escalation, where mob vigilantism is formalised into armed, organised street militias. Right-wing vigilantism has a long history in South Africa. In the 1980s, the apartheid government used both gangs in the townships and, as discussed by Paul Erasmus in his memoir Confessions of a Stratcom Hitman, a shadowy white extremist organisation nicknamed Scorpio to suppress political resistance. Since 1994, there have been regular incidents of brutal “street justice” against alleged criminals.

Related article:

But Dlamini represents a very contemporary form of politics. As with authoritarian leaders like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsanaro and Rodrigo Duerte, he presents himself as a voice of the disenfranchised masses. His use of an anti-establishment image is for highly reactionary ends.

He claims that Operation Dudula is only against undocumented people and is not opposed to legal migrants. However, its tactics send a different implicit message of “foreigners out now” – more specifically, African and Asian migrants. Operation Dudula has yet to speak out about the presence of wealthy European criminals in South Africa, such as jailed Czech fugitive Radovan Krejcir or Serbian crime syndicates.

Like Trump, he is a chameleon who has an established record of grifting and con artistry. Before settling on political incitement as a career, he registered a string of failed shell companies and claimed to own an airline.

Violence by proxy

The manner in which Operation Dudula incites violence while publically claiming to be peaceful is itself a strategy that has been called “stochastic terrorism”. The constant demonisation of certain groups is used to create a situation where mob violence is inevitable but right-wing leaders can maintain they were not directly involved in it.

Much of the media commentary on Operation Dudula has correctly pointed out how migrants are being used as scapegoats for the social problems caused by rampant inequality, joblessness and government corruption. In a situation of generalised social misery and hopelessness, people with different identity documents and accents become cyphers for all the hatred and anger felt against a self-serving, incompetent ruling class.

However, while socioeconomic dysfunction and the grinding brutality of daily life create the reservoirs of frustration and hate on which vigilante groups thrive, their politics go beyond mere scapegoating.

Related article:

Throughout the world, miltarised movements that organise around explicitly xenophobic politics are in ascent. In order to understand and, more importantly, to challenge this in South Africa, we need to confront both their politics and their psychology, and how this occurs as part of a wider crisis of capitalism.

In India, violent mobs associated with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party openly organise pogroms against Muslims on social media channels. Since at least the 1990s, the United States has seen hard right-border militias terrorise migrants on the southern border. And the past decade has seen the emergence of the Proud Boys and the Boogaloo movement, which aim to instigate a civil war against what they perceive as degenerate leftists.

The Proud Boys, which was founded by Vice magazine co-founder Gavin McInnes, played a key role in the storming of the US Capitol in 2021. Its logo was attached to stickers that claimed to be Afghan refugee hunting permits, though the group denied that these came from one of its chapters.

In the European Union, neo-Nazis organise border patrols, while other right-wingers crowdfunded “anti-migrant” boats in the Mediterranean Sea. In 2019, German authorities uncovered a plot by fascists in the elite Bundeswher military unit, which included creating “enemy lists” of public figures considered too sympathetic to refugees.

Subverting authority

These extremists have an ambivalent relationship with state power. Vigilantes often see themselves as an extension of law enforcement, which uses violence to uphold social hierarchies. The Ku Klux Klan, originally founded to prevent democratic organising by freed slaves after the American Civil War, has long enjoyed the tacit support of white supermacist police officers and politicians. More recently, Kyle Rittenhouse, a teen militia member who killed two anti-police-violence protesters in 2020, believed that he needed to take up arms to defend the police from leftists.

However, by brandishing weapons and committing public violence, right-wing vigilantes challenge the symbolic authority of the state. These spectacles are intended to not only spread fear, but also to win concessions from governments. The contemporary far right uses the image of power to push authorities and political parties to adopt more brazenly xenophonic language and policies.

Their is a particular danger of this co-option in South Africa, where the government uses xenophobia as a convenient distraction from its extensive failings. Operation Dudula claims that it wants to collaborate with the police, and given how the government seems incapable of controlling incidents of public violence, this is likely only to empower it – and even more extreme groups – in the near future.

Related article:

Right-wing extremism has flourished in a state of generalised crisis since the 2007 financial meltdown and the 2020 pandemic. Rather than intervening for the benefit of the majority, many governments have been exposed as the administrative wing of the billionaire class and have no credible responses to worsening social and ecological collapse. In the coming decades, global warming will cause the forced migrations of millions of people, and the far right is pre-emptively organising for this by agitating for higher walls and more entrenched hatreds in the present.

The social crisis is also played out in the individual psyche, where people are torn between the mythology that anyone can make it in capitalism and the crushing reality of austerity and declining living standards. This contradiction is particularly extreme in a hyper-unequal society like South Africa. Johannesburg’s Diepsloot township, the site of recent xenophobic attacks, sees absolute immiseration contrast with the nearby elite and gated Steyn City, which features the largest personal home on the African continent.

When society thwarts people’s basic aspirations, some will respond with malice and look for enemies. The danger, as the German philosopher Hannah Arendt argued about the rise of Nazism, is that when society frustrates people’s “normal functioning and self-respect, it trains him for that last stage in which he will willingly undertake any function, even that of hangman”.

The power of hate

Operation Dudula has a powerful emotional appeal for its supporters. On the one hand, it gives them an ultra-simplistic and moralistic explanation of social ills, according to which South Africa can be made great by purging outsiders. On the other hand, by enabling a carnival of militarism and intimidation, it gives them a personal sense of power and prestige.

Some of the leftist commentary on Operation Dudula has simplistically reduced it to a case of “false consciousness”: if the disenfranchised could realise that their problems are caused by the system, not migrants, they would embrace a more progressive politics.

This underestimates how paranoia, hate and the prospect of violence are, in fact, part of the movement’s very appeal. A figure like Dlamini is not merely a “morbid symptom” of the failings of capitalism, but also represents deeper problems of intolerance, insularity and a patriarchal South African media culture that too easily awards platforms to men spouting aggressive rhetoric and parading around like toy soldiers. We need to go beyond just critiquing scapegoating and challenge the entire miasma of authoritarian fantasies and delusions expressed in xenophobia.

In turn, much of the general media discussion on Operation Dudula reverts to the conclusion that law enforcement and the state must assert their legitimacy to stop the momentum of these militia-type groups. This is highly naive. The South African Police Service has shown sustained hostility to non-violent democratic organising since 1994 while showing, in contrast, an inability to respond to far more dangerous crowd violence, such as the July 2021 riots. Given its established record of harassing and extorting migrants, it should not be considered an ally, let alone a neutral arbiter.

Related article:

Simultaneously, Cyril Rampahosa’s statement that, instead of supporting Operation Dudula, South Africans should collectively fight crime, is just another platitude from a spineless president incapable of restraining even the most egregious criminality in the ANC.

Their is no “normal” to return to; the only meaningful way to defuse organised xenophobia is to drastically change a state and economy that is built on predation and condemns the majority to a life of cruel immiseration.

We need to contrast the toxic groupthink of Operation Dudula, which will achieve nothing but more divisions and hatred, with constructive forms of solidarity. In the aftermath of the Durban floods, the operations of groups like Gift of the Givers or Abahlali baseMjondolo, which use inclusive language and focus on helping people at grassroots level, expose the hollow narcissism of demagogues like Dlamini.

Rather than trusting compromised police and intelligence, progressives can take inspiration from how anti-fascists groups have organised against far-right vigilantes in Europe and the US. This does not have to mean aggressive street confrontations. It means researching and exposing their leadership, understanding how their membership think and countering their social media propaganda. It is imperative not only to challenge but also to actively demoralise their leadership and erode their mass support base.