A place weeping

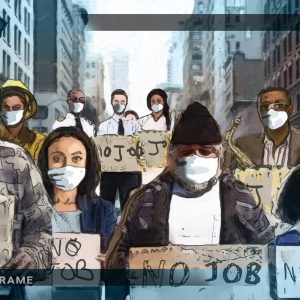

The social devastation of mass unemployment renders South Africa a non-viable society for millions. Something must give.

Author:

4 June 2021

Unemployment in the United States peaked at 24.9% during the Great Depression. On the eve of Adolf Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933, unemployment in Germany was at 24%. The protests that launched the Arab Spring in 2011 were ascribed, in part, to what the International Labour Organization called an “extremely high youth unemployment rate of 23.4%”.

In Gaza, the unemployment rate was 43.1% at the end of last year. We know what Gaza is. It is a ghetto formed by violent dispossession and sustained with violent repression. It is walled and surveilled. Its residents are subject to routine organised humiliation. There are organised ideological attempts to expel them from the count of the human race. Their protests are met with ruthless and spectacular violence.

In a 2009 essay on Gaza, John Berger, a writer for the ages, borrowed two lines from Kurdish poet Bejan Matur: “A place weeping enters our sleep / a place weeping enters our sleep and never leaves.”

Related article:

In South Africa, unemployment is at 42.3%. The rate for young people is 74.7%. The scale of this social devastation is extraordinary in global terms. A 2019 survey placed the youth unemployment rate in the country, then calculated at 57.47%, as the worst in the world – a position it has held since 2017.

Millions of young people find that the world does not extend them any kind of welcome. They are, in the words of poet Lesego Rampolokeng, “frustrated hoisted then dropped against the rocks of promise”.

Millions of people endure blocked lives, passing time in a stasis marked by tightening circles of shame, failure, fear and despair. Some start to sleep most of the day. Some turn to transactional forms of religion, offering submission in the hope of reward. Some succumb to the temptation to dull their pain with cheap heroin. Some take what they can from who they can, how they can. Some, often supported by the grace of family, friends and community, manage to find a way to hold on to enough hope to keep going.

People rendered as waste

The weight of what all this means for these people and their families, the colossal squandering of their gifts and possibilities, are not taken as a crisis for our state, the people that govern it or most of our elite public sphere.

Lives are rendered as waste, voices as noise rather than speech, protests as traffic issues or crime. People are told that their suffering is a matter of personal failure, their attempts to cope with their situation consequent to moral dissolution. They can be murdered by the state during a protest or an eviction without consequence.

Related article:

It is unsurprising that the demand to be recognised as human is often central to the language of popular protest. It is telling that the phrase “service delivery protests” is relentlessly imposed on much more complex phenomena by those whose unconscious investment in organised dehumanisation is such that they simply cannot recognise that the plainly expressed yearnings of the oppressed often extend far beyond aspirations for the basic means to sustain bare life.

It is not uncommon for thousands of people to apply for jobs that offer drudgery, exploitation and exhaustion for meagre rewards. People have died in stampedes for these kinds of jobs.

New forms of work are often precarious, and often organised with the aim of ensuring that employers can avoid the obligations imposed by generations of trade union organisation and struggle. The unions operate on the terrain of constant crisis, gearing up to oppose austerity in the state and fighting a long, losing battle to retain jobs as deindustrialisation escalates.

Exclusion from the count of the human

Neither democracy nor the NGOs calling themselves ‘civil society’ or the public sphere are really taken to include the people as a whole. Millions of people just don’t count as people. Weeping enters their sleep. It comes to sit in their bones. It comes to structure their sense of themselves, their place in their families and their understanding of the world.

We know what Gaza is. But do we understand what South Africa is?

South Africa is a chunk of territory, its borders drawn by an invading force, its people violently conquered, enslaved, dispossessed of their land, wealth and autonomy, contained in ghettos and forced into forms of labour – domestic, agricultural and industrial – structured as racial servitude. Violence built a system of racial appropriation, exploitation and exclusion, and violence sustained it.

Related article:

The sequence of popular organisation and struggle that began in Durban in the early 1970s moved into the Soweto revolt and then the growing power of the trade union movement. The urban insurrection that followed in the 1980s, often organised by or in the name of the United Democratic Front, raised the possibility of radical democracy, popular power and deep structural transformation.

But an alliance between contending elites, backed by imperialism, was able to take the initiative in the early 1990s and follow the broad outlines of the standard path towards liberal democracy developed at the end of the Cold War. The people were thanked for their service, given rights on paper and sent home.

The ANC in power moved swiftly to co-opt or dissolve grassroots organisations, while union leaders were brought into the new circuits of state, corporate and party power. It was able to begin to make progress towards the deracialisation of the middle class and elites through enabling legislation and other forms of regulation. Later on, a new class of politically connected elites became wealthy – sometimes massively wealthy – by appropriating public funds. Impoverishment and inequality worsened.

Repression

When new social movements like the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign and the Landless People’s Movement emerged at the turn of the century, they were met with paranoia and repression. When popular protest, usually organised through road blockades marked out with burning tyres, began to become a ubiquitous backdrop to everyday life from 2004, protesters were murdered by the police at a steady clip.

When a movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo, emerged from these protests, it was met with slander, assault, arrest, torture and murder. When workers on the platinum mines struck outside of the authority of a co-opted union in 2012, they were massacred.

Related podcast:

The ANC was committed to opening access to elite spaces, but it showed no commitment to fundamentally transforming society in the interests of the majority. The question of who has access to the fortified nodes of wealth was, and remains, intensely contested. The question of what happens to the people locked out remains largely ignored, apart from empty and often cynical rhetorical gestures.

Where there have been advances, such as the expansion of the grants system or the antiretroviral rollout, they were not aimed at achieving anything beyond sustaining bare life. RDP houses were smaller and more poorly constructed than the township houses built under apartheid, and often extended rather than contested the logic of colonial spatial planning.

A non-viable society

There is no commitment to the flourishing of the majority, let alone to a fundamental shift in political and economic power.

As grants come in, the money is taken to the supermarkets, to white capital. The state has not even bothered to undertake a project as basic as serious urban land reform and support for small-scale farming cooperatives and markets that would allow impoverished people to grow their own food and sell it to each other.

Across space and time, very high rates of unemployment, especially among young people, have led to major social upheaval, sometimes taking progressive forms and sometimes marked by an attraction to authoritarianism and a will to scapegoat vulnerable minorities. South Africa is not a viable society for a large proportion of the people who live here, and if history is a reliable guide to the future, something will have to give.

Related article:

The question is what gives – and what comes next? Will an authoritarian figure bent on displacing the crisis onto migrants step into the breach? Will our politics throw up more of the sort of crude chauvinists who took the recent by-elections in Eldorado Park? Will we have to endure our own Trump or Bolsonaro?

Will there be a long stasis in which the impoverished majority is governed with escalating violence as the better-off take what they can before getting out? Or will there be new forms of democratic popular power able to make some progress towards bending the state to their will, disciplining capital and insisting that every life be counted as a life?

None of these possibilities are foreclosed, and there are many more. But what is certain is that most of our people are young and urban, and most of them are without work. No social force will be able to decisively shape our future without the participation or sanction of these people.