A little man in a big moment

FW de Klerk presided over a bloody transition from apartheid. This history, and his failure to reckon with it, leave a legacy that is irredeemably compromised.

Author:

12 November 2021

When FW de Klerk stood up in Parliament on 2 February 1990 and announced the end of the state of emergency, the release of political prisoners and the unbanning of liberation movements, time stood still. The world, catching its breath, turned its gaze to Cape Town.

Nine days later, Nelson Mandela walked free. The world exulted. But the years to come were years of blood and iron as the Right, Black and white, and in and outside of the state, pushed against the movement of history. The price for every step taken towards democracy was paid in blood.

Parliament had not seen an event of the magnitude of De Klerk’s announcement since 6 September 1966, when Dimitri Tsafendas stabbed and killed Hendrik Verwoerd. Apartheid was at the height of its power and Tsafendas, a lifelong communist, was moving against the weight of the present, giving himself to be crushed by that weight.

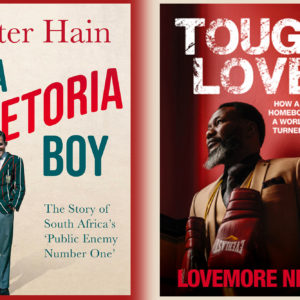

Related article:

De Klerk was moving with that weight, moving towards a Nobel Prize and, in due course, a comfortable retirement. The Berlin Wall had fallen on 9 November 1989. The Western powers that had backed the apartheid state – along with reactionary movements across the region such as Renamo, Unita and Inkatha – now saw South Africa as an embarassment, a liability to their ambitions for global domination rather than an anti-communist ally, as they had during the Cold War.

The year before, the South African Defence Force (SADF) had lost the military supremacy it once held across the region when it met the People’s Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola and soldiers from Cuba at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale in southern Angola. In a critical development, the Cubans were able to impose decisive air superiority.

A regime encircled

De Klerk’s regime was also internationally isolated, broke and confronting a powerful labour movement and the mass-based struggles loosely organised through and around the United Democratic Front (UDF), as well as an urban insurrection that had been sustained since 1984. The imposition of the state of emergency in 1985 had made it impossible to spin the old line, much like that used by Israel today, that apartheid was an isolated beacon of democracy and “Western values” in an angry sea of racially determined authoritarianism.

The Afrikaner establishment was also losing small but influential parts of its intelligentsia and youth. This intelligentsia had included dissidents at its margins since the days of Bram Fischer, a leading communist, and the theologian Beyers Naudé; and the literary movement the Sestigers (writers from the 1960s), in which the novelist Andre Brink and the writer and painter Breyten Breytenbach were leading figures. But now dissent was moving closer to the centre and cohering around the Vrye Weekblad newspaper and the Voëlvry youth movement, which pivoted around the charismatic figure of Ralph Rabie (Johannes Kerkorrel) and his Gereformeerde Blues Band.

If a figure as loathsome as Adriaan Vlok or Magnus Malan had held the presidency in 1990, he would have held course against the weight of history and taken the whole country into the scorched earth of outright war. De Klerk had no Damascene moment of ethical transformation, but he was pragmatic enough to understand that defeat was inevitable and to aim to negotiate a compromise, a way out.

But the turn to negotiation did not mean that violence was shut down. At this point, the state’s capacity for violence extended beyond its police, military and intelligence, and included the classic Cold War counterinsurgency tactic of informal militias. Operation Marion, an SADF operation, had begun military training for members of amabutho (regiments) affiliated to Inkatha in 1986, sending them to the Caprivi Strip in the northeastern corner of what was then South West Africa.

The first group of men trained in this operation attacked the home of UDF activist Bheki Ntuli in KwaMakhutha in Amanzimtoti, Durban, on 20 January 1987. Thirteen lives were lost. In January 1988, Inkatha leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi requested, and was given, further military support. On 3 December that year, 11 people, including a four-year-old child, were murdered in an operation in support of Inkatha carried out by the police in Trust Feed, a rural village in the sugar cane fields around New Hanover in what was then the Natal Midlands. Residents had elected their own committee – the Trust Feed Crisis Committee – in 1986 and refused to have it displaced by the authority of local Inkatha leader Jerome Gabela.

An accumulation of murder

This kind of violence would continue after De Klerk’s turn to negotiation and while the state was under his authority. The earth would be scorched for some as the forces of reaction sought to bend the sudden political opening in their interests.

On 23 March 1990, Buthelezi and the late Zulu king Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu met with a number of amakhosi (leaders). It is said that the king told amakhosi that the new and now rapidly unfolding political developments would threaten their power. An Inkatha rally was held in Kings Park Stadium in Durban on 25 March, and on the same day amabutho loyal to Inkatha, at least some under the direct command of Midlands Inkatha leader David Ntombela, swept into Ngaphezulu, a neighbourhood in the north of Edendale in Pietermaritzburg, attacking communities aligned to the UDF and the Congress of South African Trade Unions. The attack continued for seven days and came to be known as Impi Yezinsuku Eziyisikhombisa – the Seven Day War. At least 80 people were killed and 20 000 made homeless.

On 22 July, Inkatha launched itself as a political party – the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) – in Sebokeng in Vereeniging. On that day, its supporters killed 19 people. Another 30 people were killed in Sebokeng between 23 and 25 July, and another 13 in early August. In the same month, about 120 people were killed in Soweto, about 150 in Tokoza and 24 in Katlehong.

Related article:

The killing went on and on, month after month. Twenty-six people were killed in the Tladi shack settlement near Merafe Station in Soweto in September and 16 in Naledi, also in Soweto, the following month. In November, 45 people lost their lives in Katlehong and 13 in Dobsonville. In Tokoza, 115 people were killed in December.

The use of informal militias as a counterinsurgency tactic is deliberately murky, and typically organised by or in relation to semi-autonomous and clandestine elements within states. Throughout this period of killing, there were consistent allegations of police involvement in or support for attacks launched by Inkatha. These were denied by the state. But in October 1991, police officer Brian Mitchell stood trial for the Trust Feed massacre and it was now a plain and public fact that the police and Inkatha had worked together to murder.

In denial to the end

Things came to a head on 17 June 1992. At around 9.30pm, an Inkatha-aligned ibutho (regiment) raised from a muster of around 300 men from the KwaMadala hostel in Sebokeng attacked Boipatong and the adjacent Slovo Park shack settlement, asking, “Ziphi izinja zikaMandela (where are Mandela’s dogs)?”

Forty-five people, including a nine-month-old baby, were killed in the attack and a number of others maimed. The next morning, Cyril Ramaphosa and Joe Slovo visited the settlement. Desmond Tutu visited the following day. On 20 June, De Klerk visited under heavy police guard. Residents chanted “to hell with De Klerk” and rushed his security convoy. He was trapped in the car for around 15 minutes, and then able to leave with people chasing and stoning his convoy. The police shot and killed one person.

Nelson Mandela visited the following day. Speaking on the brown winter veld where the police had shot at the protesters the day before, Mandela, angered to his core, said: “I am convinced we are no longer dealing with human beings but animals … We will not forget what Mr De Klerk, the National Party and the Inkatha Freedom Party have done to our people. I have never seen such cruelty.”

Later, testifying at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Johannes Mbatha, a resident of Slovo Park whose wife, Paulina, was rendered a quadriplegic during the attack, said that police officers were present as the settlement was stormed. “I cannot tell a lie, I even saw their cars. I thought I was dreaming. I could not believe the police were there in uniform.” He testified that he followed the attackers as they left, and saw them get into police Casspirs.

The failure to investigate these attacks properly means that much remains murky. But while we may never have a credible public record of exactly what happened in each instance, and the degree to which local actors may or may not have operated with a degree of autonomy, there is no doubt that De Klerk must, at the very least, have had an overall sense of what the alliance between parts of the security forces and Inkatha meant. His failure to accept responsibility for all this killing is indefensible. He was in charge. He had the power to stop the killing. Leon Wessels, who held a Cabinet post in De Klerk’s government, told the TRC that “I do not believe the political defence of ‘I did not know’ is available to me because in many respects I believe I did not want to know”. If there were cases where De Klerk did not, as he claimed, know how the killing was organised, it was because he did not want to know.

The apology, issued in very general terms, that De Klerk left to be circulated after his death does not change this. An apology not given before the face of the other, given in the absence of the living presence of self, is an act of a coward seeking cheap redemption.

De Klerk was, for a moment, illuminated by the lights of a great moment in history. But he cast no real shadow. He was, in the end, a very little man who never found the courage or integrity to honestly confront his place in that history.