Answer the siren call and make the elites fear it

This first in a two-part series tells the story of how Narayan Gaikwad, a crusader for social justice in rural parts of India, became a leading activist for the rights of farm workers.

Author:

15 April 2021

Narayan Gaikwad is thankful to have dropped out of school in grade 11, in what would be known today as one of his two higher-secondary years, the final being grade 12. “I had a terrible toothache and could no longer walk 9km to the school,” he says.

After an incorrect diagnosis, the 18-year-old teenager endured the pain for six months, attempting every possible home remedy he could concoct in Jambhali village, his home in India’s Maharashtra state. He then consulted another dentist, Vijay Parekh, who said he had cavities that needed to be filled and it would cost 65 rupees, or about R13. This was in 1965.

Gaikwad could not afford it. “After crying for months, my mother gave me 10 rupees. From where will I bring six times the amount?” He was back at his solution of enduring the pain, but four months later he lost his calm. “I went to the farm, took pliers and removed the teeth.” His drastic action would lead to a scary result. “The bleeding just wouldn’t stop,” he says five decades later.

Gaikwad then walked 9km from his home to meet Parekh again in the town of Ichalkaranji in the Kolhapur district. The dentist’s immediate reaction was, “Are you dumb? What kind of a person are you? Who asked you to pluck your teeth?” Gaikwad replied, “I was helpless. I don’t have the money even today.”

The forlorn look on his face revealed much more than his pain. And with a few questions, Parekh diagnosed far more than cavities – and changed Gaikwad’s life. “How much land and cattle do you own? What crops do you cultivate? How many members are there in the family?

Hearing the answers, Parekh yelled, “There’s bourgeoisie in every village, and you are all exploited by them.” A tired Gaikwad, for whom these ideas were alien, asked what bourgeoisie means. The answer left him with doubts. He found the doctor’s conversations interesting and returned the next day to pay his gratitude. “I wanted to learn more,” he says, and volunteered to work as a compounder, mixing medicines.

Enlightenment

It didn’t take long for Parekh to introduce Karl Marx, Fidel Castro, Che Guevera, Rosa Luxemburg, Vladimir Lenin and other revolutionaries to the young farmer. His words made Gaikwad identify the root causes of exploitation in his village of 4 030 people: “Capitalism and bourgeoisie.”

Gaikwad would wake up at 4am daily, finish his farming work by 9am and then leave for the clinic, where he was also tasked to bring books from Ichalkaranji’s 151-year-old library. “Those books on the Soviet Union and the Russian Revolution were so heavy,” he recalls, laughing.

He once asked Parekh, “How will a revolution be possible in India with several superstitious beliefs and no unity?” Parekh handed him a book on the socialist revolutionary Bhagat Singh, which allowed Gaikwad to absorb the tales of revolution.

-

Kusum and Narayan weighing the harvested Sorghum. -

Narayan’s wife Kusum has always been supportive of his call to protest. She looks after the farming most of the time. In this photo, she is extracting the castor oil using the traditional method.

Guevara’s words “Let the world change you and you can change the world” served as an inspiration to Gaikwad, who had only been to a handful of villages by then. Parekh, who was in his late 20s, asked him if he wanted to visit India’s financial capital, which was then Bombay, now Mumbai. “We would stay in Mumbai at least for a month and meet the Communist Party of India (Marxist) leaders like BT Ranadive,” recalls Gaikwad.

Parekh took him to the city’s shack settlements, prompting Gaikwad to ask, “Why are people living like this? Who is responsible for this?” Throughout the night, they would discuss the works of Marx, Lenin and Luxemburg and talk about the communist parties of Vietnam, Cuba, Hungary, Chile and those in Africa, as well as India’s anti-superstition movements.

Related article:

Back home, they soon decided to offer medical services to the rural people in Kolhapur district. With four or five doctor friends, they started a free medical camp on Sundays. “We would give medicines and treat at least 50 people every week,” says Gaikwad. With these camps, the dentist would also make people aware of how they were exploited by the bourgeoisie. Eventually, local politicians were successful in dissuading villagers from visiting the camps.

“In a democracy, it’s important to build a ground movement,” says Gaikwad, whose understanding of the huge caste and class divides in his own village was deepened by the camps. And though they stopped, his spirit wasn’t dampened. “I never left the path of social justice. I am at it non-stop.”

The first protest

The drought from 1972 to 1973 severely affected 57% of rural Maharashtra’s population of about 20 million people. As a relief measure, the government began employing drought-affected people to construct roads. For 2 000 workers, the order was to construct a 6km-long road between Jambhali and Takavade within two days.

Gaikwad, 25 at the time, was angered by this exploitation. He disguised himself as a labourer and called a meeting of 1 500 workers. “What work will you get later if you finish the work within two days?” he asked. “How can you work 14 hours without using any machine and safety gear?” He appealed to the workers to finish a day’s work in 10 days.

What followed was a major protest. “For three days, we halted the work.” Gaikwad warned the contractor, “We are all humans and won’t complete this work in a day.” With mounting pressure, an official showed up on the third day, saying, “Take how much time you want, but don’t stop the work.”

This success would make the local newspapers. “That’s when comrade KL Malabade came to meet me from Ichalkaranji,” Gaikwad recalls proudly. Malabade, a veteran Communist Party of India (Marxist) member and workers’ leader, was elected a member of Maharashtra’s legislative assembly in 1990.

He offered Gaikwad a chance to attend the party’s meetings. Gaikwad, who sold vegetables on Mondays and Fridays, began reading books at the party office in Ichalkaranji. “I would read for three hours every day, which helped me develop a deeper understanding of class struggle.”

Unionising workers

In Kolhapur’s Shirdhon village in 1992, women agricultural labourers were paid three rupees and men five for toiling 10 hours in the field. Gaikwad knew he had to unionise the workers. Predominantly, the agricultural labourers belonged to the lower castes and so he decided to stay in their takkya (community hall).

“For a month, I spoke to people, organised meetings and started planning the protest,” he says. Saubai Nilajge and Vimal Kamble would help him mobilise the women labourers. “Every day, we would organise meetings of 100 women secretly,” recalls Nilajge, now in her early 80s.

Meanwhile, Gaikwad inspired them with his powerful oratory skills. “We had blocked all the roads and deployed 50 women labourers at every corner,” he remembers. This was the beginning of a week-long protest for a pay hike. A rich farmer, however, was ferrying labourers in defiance. “Saubai quickly pelted four stones on his tractor. Scared, the owner ran away,” says Gaikwad, laughing.

Three decades later, Nilajge remembers, “I snatched away sickles from the women and asked them not to work. It was our fight.” Ask if she feared the farmer, she replies, “I pelted four stones. Had he done something, we had 500 women labourers on our side.”

It took a week for the block-level officials to intervene and increase the pay to seven rupees. Five years later, the workers protested again for three days, leading the pay to increase to 11 rupees. “The police officers would support us because they knew about the lives of women labourers,” says Gaikwad. Nilajge adds, referring to the plight of these landless labourers, “We don’t have anything other than the sickle.”

In retaliation, the rich farmers now made them work 12 hours a day, so Gaikwad demanded a siren from the labour officer. “This village siren helped regulate the work time, and as it rang the workers stopped working,” he says. Gaikwad installed another siren in Kurundvad, which is also in the Kolhapur district. “The corporates and the bourgeoisie always fear the siren,” he says with a wide grin.

In five years, he built unions in the villages of Arjunwad, Shirdhon, Rui, Kothali, Sajani, Tilwani, Rukadi, Jambhali and Takavade, all in Kolhapur.

Another issue was farmers’ use of exorbitant amounts of chemical fertilisers to maximise their profits. “You could see acid tearing apart the skin,” Gaikwad says. With no protective gear, the workers would often report skin infections and could barely walk. He began meeting labour officials to address the issue, but they ignored him.

Gaikwad then led another protest in Shirol, after which the farmers gave their workers safety gear. He also got paid sick leave approved. This was a big feat because the farmers never signed any written contracts with the labourers, depriving them of social security. For his work, he would receive death threats from local goons. “When you work for people, you don’t fear for your life,” he shrugs.

A lifetime of protests

Gaikwad knew he had to travel extensively to understand the agrarian disaster unfolding in rural India. In the late 1980s, he began traversing as far as 2 000km from his village to Samastipur in Bihar to protest against the government’s pro-corporate policies. “My wife would always support me and take care of the farming.”

Four decades later, he has been to over 1 000 protests across India fighting for farmers and labourers. “He has spent his entire life protesting and helping people,” says his wife, Kusum, 66. Gaikwad has collected photos from these protests. “I would ask the press photographers to give me a copy.”

-

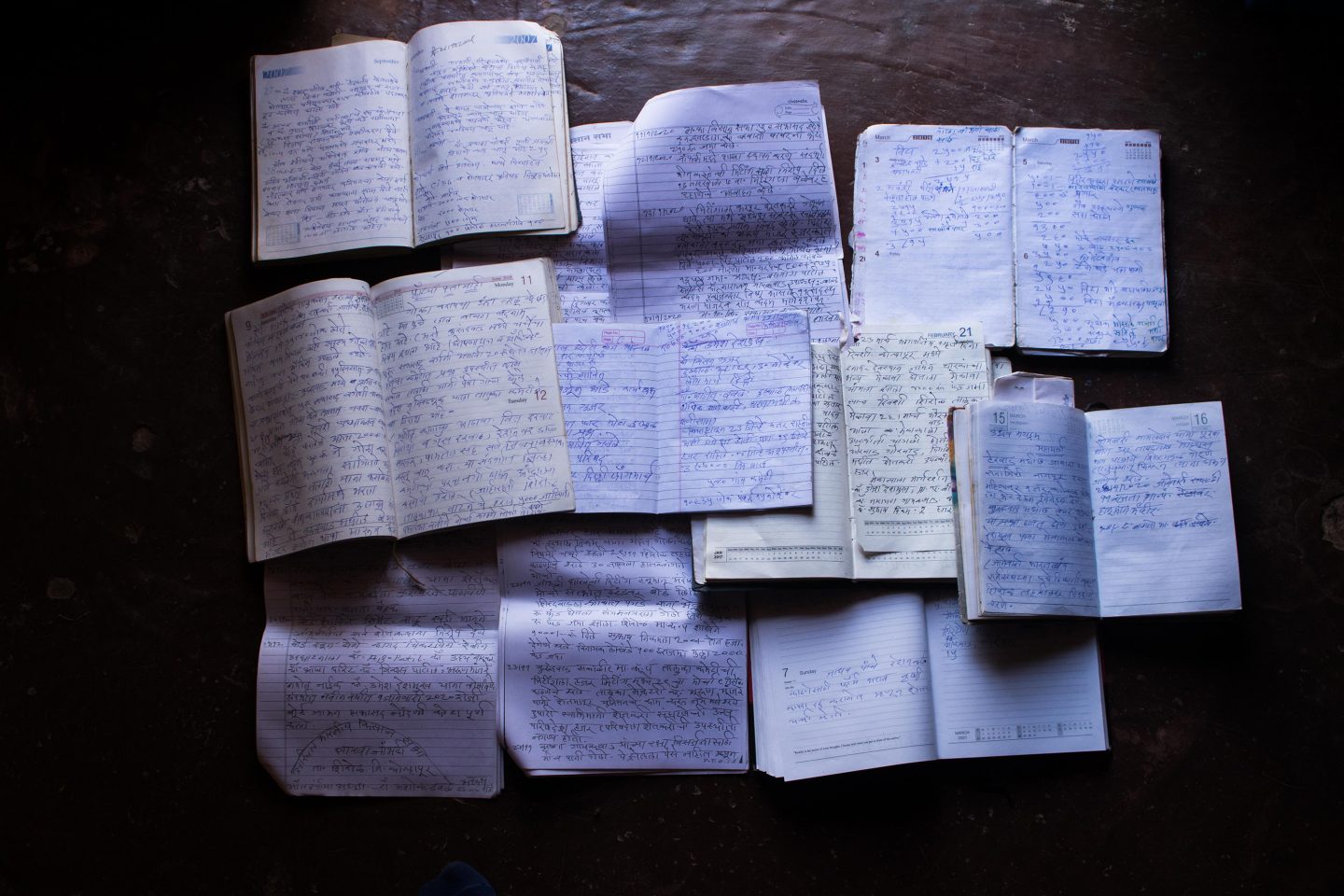

Throughout his life, Narayan has been interviewing protestors and taking detailed notes in the vernacular language, Marathi. He has hand-written thousands of pages documenting the protests and his work. -

Narayan always carries his own food to the protests and often distributes it to the protestors.

He has travelled as far as Kanyakumari on India’s southern tip, Trivandrum in Kerala, and Khammam in Telangana. In his home state of Maharashtra, he has been from Aurangabad and Nagpur to Beed and Nashik. “I’ve been to Delhi 22 times,” he says proudly about his trips to a city that is 1 683km from his village, and he has “lost a count for Mumbai”.

Things would not be easy. As per India’s neoliberal policies, American energy company Enron announced a controversial thermal power project 250km south of Mumbai in the early 1990s. It acquired 700ha of land, displacing 2 000 people. “The government had first halted the project but later reinstated it,” says Gaikwad. In January 1997, about 10 000 protesters gathered in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri district, with more than 1 200 arrested, including Gaikwad.

Human rights violations were reported as the police resorted to violence. “Privatisation of essential services is always harmful,” says Gaikwad. Before being detained in jail, he made a call to Kusum, saying, “I will be in jail and will return after eight days.” She didn’t worry. “We were not scared because he was fighting the right fight,” she says.

Gaikwad always talks to protestors and makes detailed notes in his vernacular Marathi. This has helped him befriend hundreds of protesters across India. To date, he has written more than 1600 pages of notes in his diaries. “How will you understand people’s plight if you don’t talk to them?” he asks. He also reads books and magazines to enhance his understanding of any crisis he’s about to tackle. He even carries his own food to protests and often distributes it to others.

“Had I not met Dr Parekh and become a comrade, I would have been an alcoholic or a gambler,” Gaikwad says. A modest Parekh, now in his late 70s, responds, “I did nothing. He surpassed my expectations by a hundred times. We would just talk and discuss, but Gaikwad always had it in him to fight against the injustice.”

Sanket Jain has spent 28 months documenting Narayan Gaikwad’s activism.