Athi-Patra Ruga brings the outsider in

The artist’s latest exhibition uses the power and politics of stained glass and tapestry to comment on society’s exclusions, create joy and console the grieving.

Author:

10 August 2020

“What do I do as an artist who is of service, and who is arrogant enough to believe I can console people as part of my work?” asks Athi-Patra Ruga during an interview about his new work, Interior/Exterior / Dramatis Persona, a Saga in Two Parts.

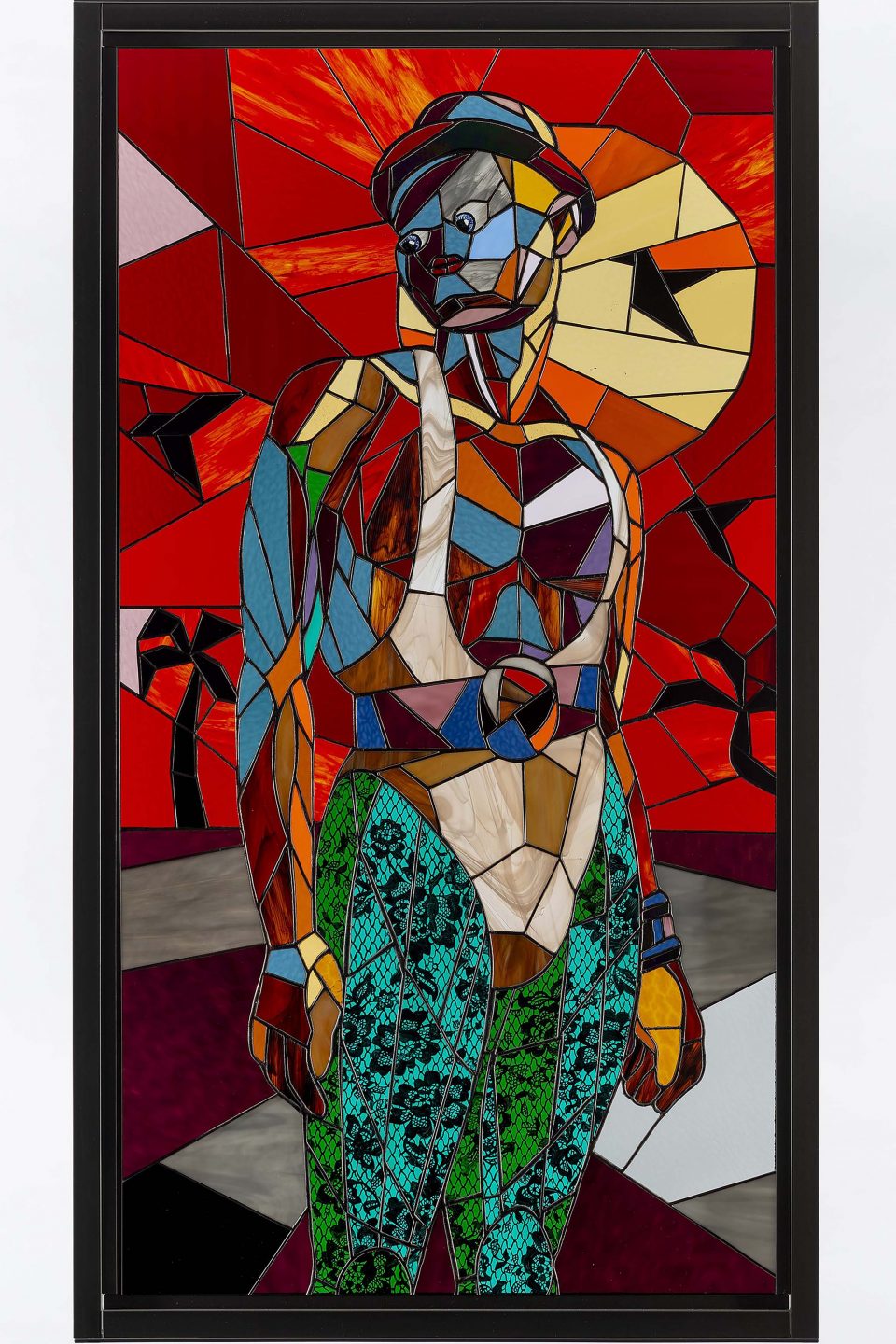

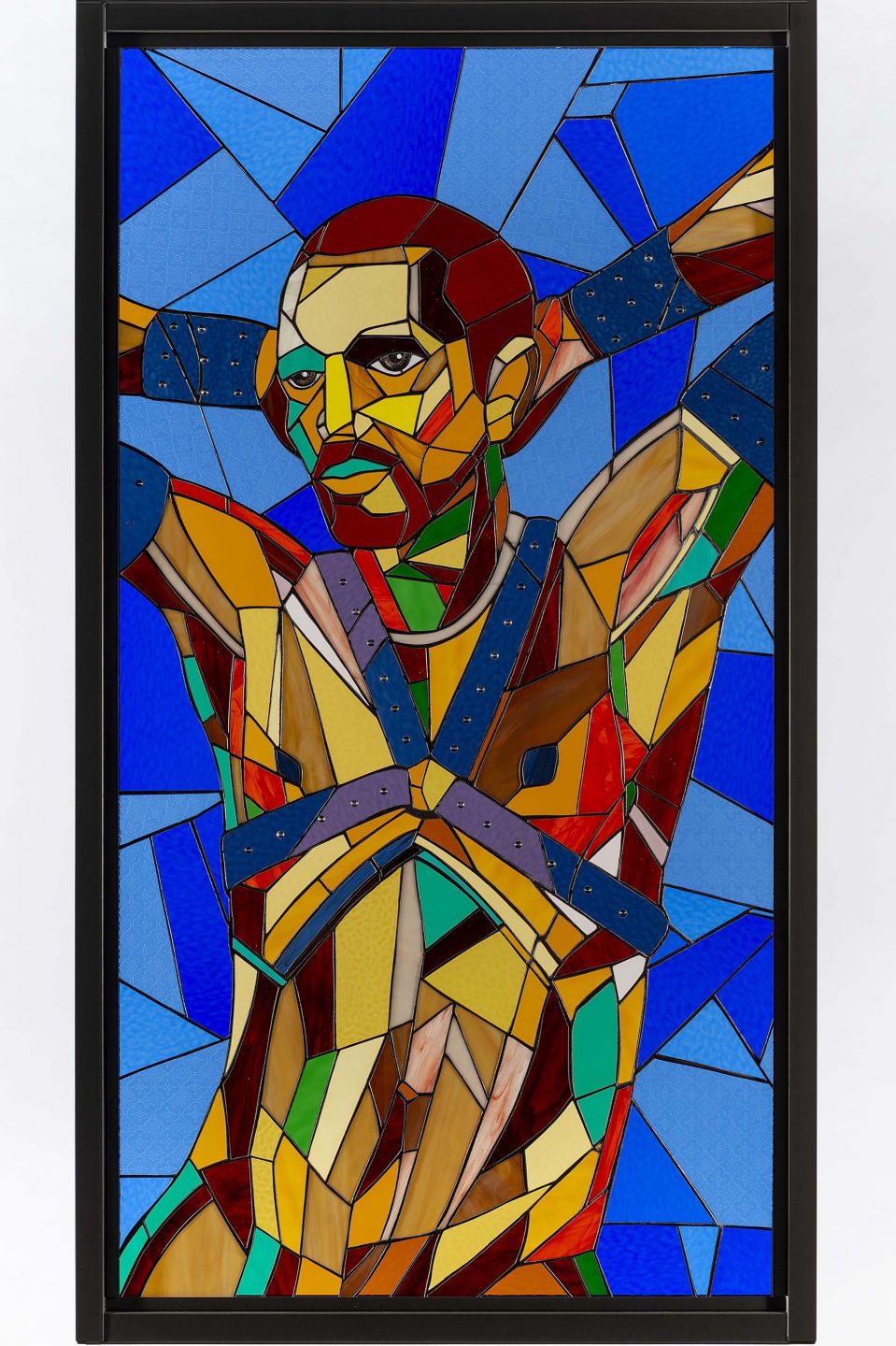

Currently showing at WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery, Ruga’s latest exhibition is a grand and evocative display of the exquisiteness of stained glass and tapestry, while being subversive in its depictions of those he calls “deliberately black, deliberately queer and deliberately femme”

Making stained glass and tapestry come alive with varying shades of brown, orange and amber, Ruga reclaims the art forms for black people who remain absent from representation in these media.

On a video call from Hogsback, Eastern Cape, the artist, who has worked with stained glass since 2013, explains that he uses the medium “we all know … as a nationalist or ecclesiastic tool to say something about who is seen – and for me that’s about taking something that’s interior and making it exterior. Stained glass says something about class. It says something about access.”

In this work, Ruga meditates on the violence of black people who love the church and the artforms but who do not see themselves in either.

The inspiration for this work arrived in two parts. The first came from the stained glass windows at St Philip’s Anglican Church in Gompo, East London. The local community insisted on depicting the divine annunciation scene with a black Archangel Gabriel and black Virgin Mary. The other emerged in wanting to reference the use of coloured glass in some black middle-income township homes, particularly where yellow and amber windows are used as decorative architecture.

This, the artist says, required that he deal with his internal feelings of shame and its relationship to classism. “I went past the fear,” Ruga says, “that … feeling that [the work] would be kitsch and decided it was more important to lift the work and my people up.”

With this exhibition, Ruga navigates the delicate and difficult relationship between the interior feeling and exterior representation.

-

All images courtesy of Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD

© Athi-Patra Ruga -

All images courtesy of Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD

© Athi-Patra Ruga -

All images courtesy of Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD

© Athi-Patra Ruga

Histories of stained glass and tapestry

In addition to using stained glass to make a comment about who society deems worthy of celestial or deified depiction, Ruga’s work also critiques art in general. The history of stained glass is a story of conquest and power. Its roots in Africa, particularly North Africa, and parts of the Middle East are obscured by its European tradition and its association with the church.

Aware of this important piece of black history, Ruga says: “There is a reason that to this day some of the best glass is made in North Africa because of the sand quality … I take the greatest comfort in the idea that I am part of a very long line of black producers, craftsmen, diviners, healers and artists, which stretches all the way from the rock paintings to kwaito. I am very aware of the history of the materials I use, which allows me to insert myself and community in there. For instance, tapestry, a very colonial art form, which was taught to me by a German woman in Alice in the Eastern Cape, I use as an expression and a way of documenting my communities.”

The stories Ruga tells throughout his portfolio, up to and including this latest exhibition, are about being in and out, about sometimes belonging and sometimes being cast aside. It is a personal story for him as someone who grew up in both the Anglican church and with amasiko [traditions].

Related article:

“Excommunication is the word I would like to use to enter the idea of interior-exterior, [whether] you are being cancelled online [or] the church doesn’t agree with your sexual orientation [or] your family cannot support you anymore because of the lifestyle you’ve chosen. The artist is also able to fit into so many spaces – so be inside while also being outside – which allows the artist to tell the stories from a certain distance. So I wanted to use that to give praise to those imaginations that are deliberately black, queer, femme and so alive, despite the killings.” Here Ruga references how precarious life is for those who claim these identities, noting how the lives of these folk are often “unrecorded, misrepresented and forgotten”.

The subjects of Interior/Exterior ⁄ Dramatis Persona are black queer men and black women, as is seen in The Speller The Killer, who wears a mask, a spandex leotard belted at the waist and a bowler hat, and Swazi Youth After, a young gay man in a body harness. In doing this, Ruga consciously highlights and works against fetishisation, exoticism and stereotype, and asserts the human, the vulnerable and the complex.

In addition to wanting to represent different kinds of brown skin through the many shades of the colour with which he works, Ruga also deals with the ways humans are fragmented. Stained glass perfectly shows fragmentation and how people are always in the process of being made. Ruga says, “That is the nature of me and the characters I talk about. We are never complete but … learning to live and luxuriate in that fragmentation is how we are hopefully able to heal.”

The theme of fragmentation also plays out in the tapestries, specifically with the story of Nomalizo Khwezi, a new character from his Lunar Songbook, described by WHATIFTHEWORLD as “a trans-media body of work informed by Southern African astronomy and a more ecological way of recounting time”. Khwezi is a member of the Anglican church, even going as far as being part of the church’s women’s guild. In thinking about her narrative, Ruga says, “she knows about the colonial history of Christianity but also derives community from communion and the resistance within the Anglican church. This represents a double consciousness from black people.”

With this body of work, Ruga showcases some of the beauty, ordinariness, joy, sexiness and seriousness of black people. He elevates brown skin to the highest levels of art represented by stained glass and tapestry while also making high art accessible, normal and what he calls “vernacular” – part of everyday language and experience.

Grief work

The wonder of something so beautiful and masterful seems even more appropriate during the Covid-19 pandemic, which is characterised by so much death – both literal and figurative. Ruga, calling himself a grief worker, says he is also aware that he will soon need to do more work in consoling, memorialising and burying members of his beloved communities because of this moment in history.

Along with representation and memorialisation, healing is a central feature of Interior/Exterior / Dramatis Persona, which draws on the big, bold and bright tradition of his previous work and deals with seriousness, even death, with joy. “I just wanted someone to feel better. There is too much pain in the world. I often get the criticism of being too much about black boy joy, but once you are liberated by it, you get to do the work that I do,” he says.

Ruga’s technicolour world is also about pushing back against the art world, where, he says, black joy is not considered serious enough or worthy of acclaim.

“I always feel that the tall, dark, serious heterosexual enigma is so much more palatable than a happy, sexual black woman or queer … I’ve been around [for] 15 years and I would be naive to think I haven’t missed out on opportunities because I don’t continue the tradition of the enigma. It’s why I’m so committed to my communities who are black, femme and alive. The use of colour and in the way I do it allows you to sit back and feel, which so many of us don’t do. It allows us to say, ‘Things are terrible but you can surround yourself with beauty.’ People like criticising beauty because they think beauty is sedate and doesn’t pack a punch. I think that if you are going to console someone, you pack more of a punch than someone who wants to destroy … A love letter and beauty can be a radical thing, and there is nothing more fortifying than knowing you come from beauty and love.”

The exhibition can be viewed in person or online at whatiftheworld.com until 5 September 2020.