Banele Khoza feels love’s reality

The artist’s new virtual exhibition continues his compelling meditations on the complexities of love. He speaks about his muses, the music that inspires him, loneliness and lockdown.

Author:

26 August 2020

Banele Khoza’s artworks are a Lang Leav poetry collection. They are the spine of Adele’s every song, feeling before thought, and the title of a bell hooks book. Like all of these labours in creativity, his artworks tenderly place love at the centre of an extended inquiry into form and feeling.

In vibrantly saturated tones and text, the artist and gallerist’s new virtual exhibition, In My Feels, is a series of digital drawings that pivots on love – and expands in other directions too. It marks two years of BKhz, his gallery in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, and also coincides with four years since his first solo show, Temporary Feelings (2016). Khoza’s work has been drenched in the multiple sides, antitheses and echoes of love’s lifeworld for years.

In My Feels is a dreamlike and transportative journey into the interior world of Khoza’s feelings: a place where hopes, longings, late night thoughts and reckonings live.

Related article:

With this body of work, he turns the inside out – making the vulnerable visible. But at Khoza’s Pretoria home, he has brought the outside in. As the artist joins a Zoom call, the lush green walls of his apartment with their pastel pink-hued paintings become visible. They are inspired by tulips, and the 40-something plants that share space with him are a physical echo of the close relationship he has with nature and the comfort he finds in it.

Born in Hlatikulu, eSwatini, Khoza visits gardens when he is lonely. He has made his home a green retreat. “I feel more at home,” he says, “because there is all this life around me.”

Love, lockdown

The conclusion of In My Feels came during the Covid-19 lockdown, a time when loneliness has been amplified for many. Khoza explains that the lockdown “just forces you to really confront yourself”, before adding: “The interesting thing is that my life just kind of always felt … in isolation, to be honest.” When Khoza recently posted content from his Lonely Nights (2017) exhibition, people responded with comments such as “Wow, you are making exceptional work”, thinking the work was recent. He laughs, explaining: “I was like, this is what I’ve been going through for the longest time.”

On the origins of his latest exhibition, Khoza says: “I think just maybe, to begin with, the honesty of this show is that I didn’t know I was working towards one.” It’s a familiar mode – his creativity flowed from feeling in an organic stream of artistic consciousness, and then a show emerged. It was only when he was pooling his new imagery that he realised there was a common narrative. “This is something I’ve been saying and, even myself, I wasn’t listening to [it],” he reflects. Khoza gets to “the truth after the work is done”. Revealing himself to himself in layers, he finds meaning after feeling.

Before In My Feels made itself present, Khoza wanted his next show to be a conclusion: “Love.” A full stop, a reckoning with a resolution. Instead, his complexly textured meditations continued.

‘A cauldron of contradiction’

Entering the virtual show, Khoza’s online dreamscape, the honesty he speaks about immediately appears. The words on his canvases and titles are drawn from his journals. Their simple and direct emotional language is clear, and often devastating.

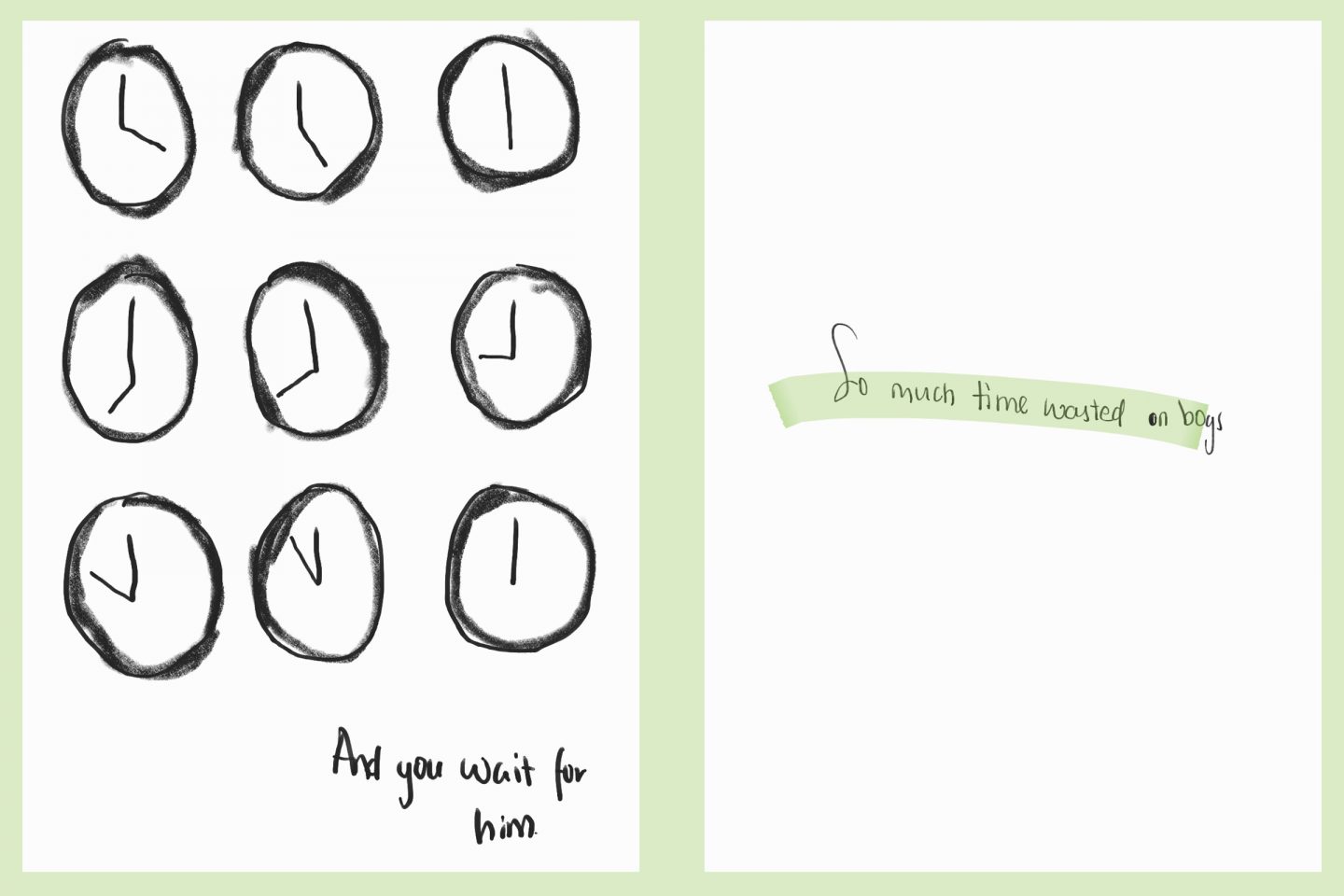

A work reads “Folks be like, this is why you are single”. Alongside multiple clocks bearing different times, he writes “and you wait for him”. And deeper into the exhibition’s walls, he muses about “so much time wasted on boys”. All these words, on single coloured canvases, are a reminder that text is image and art too.

In the foreword to her book Love, Toni Morrison writes: “People tell me that I’m always writing about love. Always, always love. I nod yes, but it isn’t true – not exactly. In fact, I am always writing about betrayal. Love is the weather. Betrayal is the lightning that cleaves and reveals it.”

With this show, Khoza is not exploring a single emotion. He is also talking to a wider breadth of feelings spinning in its orbit – and a “cauldron of contradiction” that writer Ayodeji Rotinwa notes in the lyrical essay that accompanies the exhibition, and also references Morrison.

On these canvases there is love, rejection, longing, fear, loss, confusion, lust, indifference, loneliness, and more. There is the meaning of being in relation to another. There is what it means to be human.

The bearded Gym Crush occupies one wall. But across from him, a single sentence states “I hope he treats you like somebody he loves”. A tender love letter to Khoza’s future soulmate sits right next to an individual with a multicoloured face that is a fraught world of feeling. The title? Simply, Ugh.

And on one wall, a trio of works talk to our present – a reality in which technological maps read like GPS coordinates of each other’s online presence. Instagram stories posted, a green dot appearing next to a user’s name on Gmail and Facebook, “Last seen online” and WhatsApp’s dreaded blue ticks which show that messages have been read. To a lovelorn voyeur, everything reads like a flickering light of presence and absence: “I am here, I am not there.”

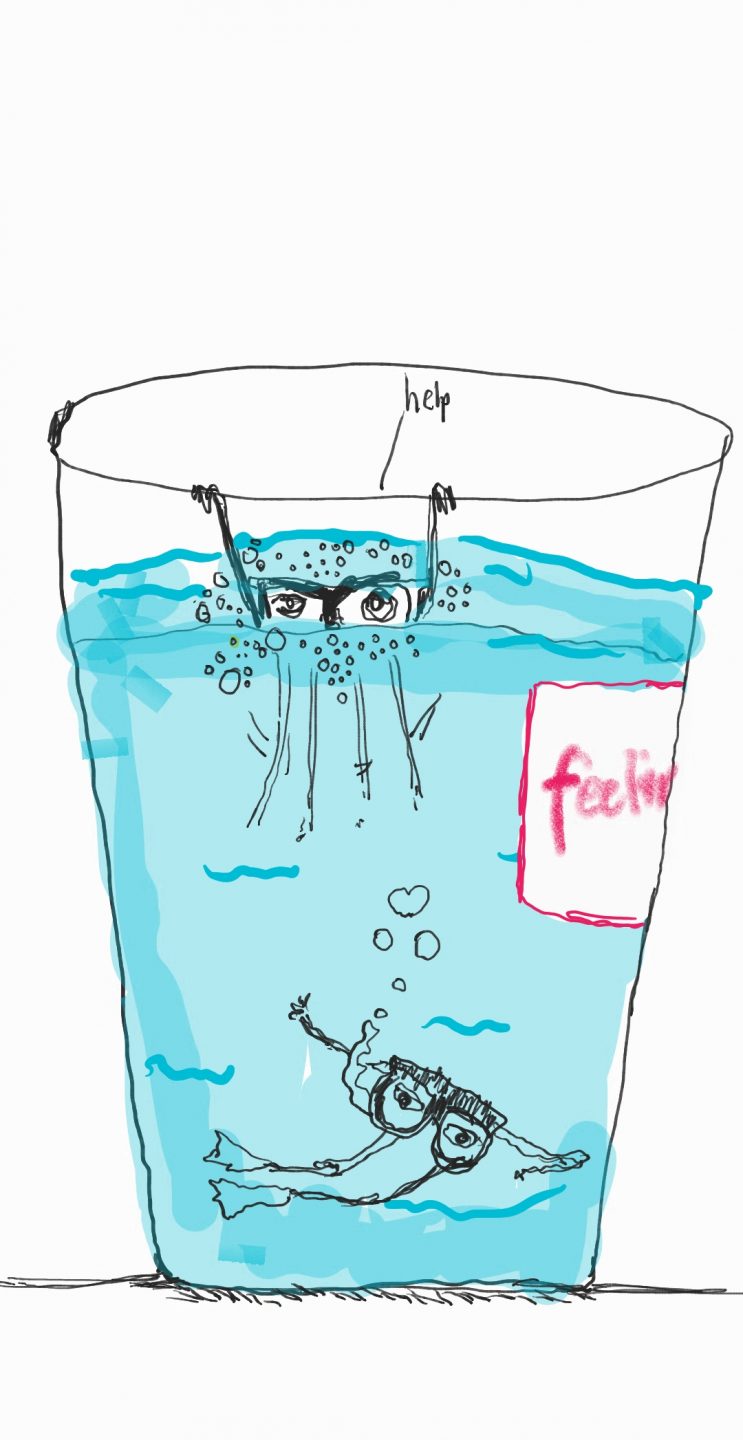

With a poignant humour, eyeglasses are made embodied. Tears fall from a pair of glasses next to the words “he cancelled”. One pair drowns in a glass of water, titled feelings, while another is safely submerged. Hitting hardest is a pair of glasses holding a check mark with the words “For All Those Blue Ticks”.

With a mastery of his form, part of the show’s success lies in exactly why Adele has sold millions of albums: it is deeply relatable. As Rotinwa writes: “In My Feels is a visual diary whose contents are all too painfully familiar, that invites the viewer to share, experience these feelings afresh.”

As Khoza expands love, takes it apart and surgically exposes its parts, the themes, ideas and feelings explored are recognisable: an ache, the joy and bruising of feeling, a search to be seen. Khoza is in his feels. But aren’t we all?

The painterly musician

The reference to Adele is deliberate. Khoza is a visual artist, but he works in the spirit of musicians – in approach, philosophy and theme. Music is central to his practice and his process.

“I like the fact that you reference Adele,” he says, “because she gave me the framework of how to work and do really good work, where it’s about the silence. You go silent about something, and in that silence you are trying to reveal a body of work. I would definitely say this is how [the show] came about…”

While inspired by artists such as Sir Zanele Muholi and Marlene Dumas, Khoza explains that, right now, he draws his primary inspiration from musicians.

In his process, Khoza extensively listens to the same albums on replay. While creating his show, he listened to Gregory Porter’s Liquid Spirit (2013) and Be Good (2012), alongside Lianne La Havas’ Blood and Corinne Bailey Rae’s self-titled album.

“I’m really sensitive to sound,” he says. “When I’m listening, it has to be an experience each time. I’m trying to connect with the dialogue of my feelings and I think that’s what [musicians] take us through. The dialogue of either their feelings, experiences, a person that they are describing or singing about…”

Khoza wanted to be a musician; he still dreams about being a ghostwriter for artists. While being mentored on how to write lyrics, however, fear got in the way. “The relationship with writing is that whatever there is on paper, there is kind of like no hiding behind that. It’s just like you set out the truth, and with paintings you still can hide. You can hide with the title, the image, people can view it the way they want to… but with words, that’s it.”

It is an interesting comment. While In My Feels appears to reveal so much, it also strategically conceals. Khoza curated this show because he knew he had to tell the story with both the titles and placement of the work. “I’m very conscious of what I’m saying – from titles, moving into layout and hiding some pieces,” he says. “For instance, [the work] My Default Type… I tried to hide it because I also have hidden that to myself.”

Reality letters

A series of questions conclude the interview as Gauteng’s skies begin to darken. “Are these [artworks] all [of] real people?”

“I’m not saying anything,” Khoza responds, before collapsing into a ripple of consistent giggles. Some people sit for the work and others are drawn from memory and imagination, he explains. It is a hyper-vulnerable, honest, intimate and courageous way of working.

Asked whether he sees the works as love letters, he pauses before extending the idea. “Not only love letters,” he explains, “but also, I would take it further to, like, I don’t know if reality letters could be it as well.”

To find language, he turns to the art. “There’s the triptych where in the painting it looks like a lady in a veil, but I know it’s me because when I like someone, I start imagining [the aisle]. I’m all the way in.” He laughs. “Then the next painting shows the cloud around the person that I do like.” And finally, “they stand on the far other side and they are not even looking in my direction, they are looking elsewhere, and they are looking pretty…”

![Left: Undated: At the Alter (2018) is part of a triptych by artist Banele Khoza that tenderly explores romantic daydreams and unrequited love. (Image supplied). Right: Undated: Reflecting on his work, Khoza says, ‘I’m very conscious of what I’m saying – from titles, moving into layout and hiding some pieces… For instance, [the work] My Default Type (2020)… I tried to hide it because I also have hidden that to myself.’.](https://www.newframe.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/26Aug_Banele_AE4-1-scaled.jpg)

Khoza does not want to work for love anymore. “Connection should be just something that comes organically without hard labour. And I think that’s where I’m at now, where I can’t chase anymore. I’m done chasing. The chase has been great but so abrasive.”

He laughs when asked, “Who do you think of as the person who is on the other end of your art? Who are you painting to?” Without words, he finds language in another’s. For Khoza, poets have been “a pivotal source of inspiration in terms of words and just the intent and power of words”.

Leav’s words, from the collection Love Looks Pretty on You, are his answer:

“You turn him into poetry because you can’t have him any other way.”

“Most times, I’m also just trying to write to that person that I wish I could tell something, but I can’t. And I see it very often, where I can see that, in the physical, the person is not trying to be with me, and then I just do almost an ode to them, either a portrait of them or saying something about them and wishing they could hear it or see it, and… No courage.” He chuckles at himself.

At the end of the interview, I ask Khoza to complete the sentence “Love is…” He pauses and giggles, head in hands. “That is a tough one,” he says. And then, with daylight fading and his hands tenderly holding his face, Khoza replies: “Love is available.”