Book Review | The Vanishing Half

Brit Bennett’s latest novel explores the lives of two Black women who go to great lengths to deny their roots and legacy, and the harm this causes to themselves and those around them.

Author:

28 December 2020

Author Brit Bennett pulls the lives of Black women from the margins to the centre of her work. Her narratives highlight the differences between these women, their multiplicity and their complex interior lives. Writing for the New York Times, Parul Seghal describes Bennett as “a remarkably assured writer who mostly sidesteps the potential for melodrama inherent in a form built upon secrecy and revelation”.

This skill is central to her sophomore title, The Vanishing Half. Through the story of twins and the hometown that forms them, the novel interrogates the consequences of colourism, racism and “white passing” in Black communities. It does it in a way that refuses and subverts the commonplace idea that solely frames colourism as opportunism, with fatal consequences. Poignant, without pathologising its characters, Bennett’s story delves into what it means to frame Black women as ambitious and violent in seeking to escape oppression and attain their dreams. “You can escape a town but you cannot escape blood. Somehow, the Vignes twins believed themselves capable of both,” she writes.

Related article:

Bennett draws back the curtain on the theatre of race and performance, introducing us to twins Stella and Desiree, who are absorbed by a desire to escape the fictional town of Mallard. The town’s residents thrive on the ambiguity of their skin, which leans closer and closer to alabaster with every generation. From its inception, the hamlet in the South has placed value on the lightness of skin and their community’s proximity to whiteness. The town is described as being for people “who would never be accepted as white but refused to be treated like Negroes”.

The Vignes twins subvert the values of the town folk in various ways, first by escaping and eventually by rupturing from one another, their paths diverging, each categorised by its own possibility of violence. Desiree and Stella flee to New Orleans in search of life not categorised by the brunt of Black labour. Running into the night, they escape from a script that would inevitably require them to fulfil the role of the Black domestic worker.

Exploring dualities

Themes of race, freedom and “passing” suffuse The Vanishing Half. Written in a style akin to Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, this book stands on the shoulders of thinkers that have always centralised Black life – and it will perhaps, too, become a modern classic, given the strength of Bennett’s work.

Bennett picks at the scabs that mar the history of blackness, particularly the phenomenon of white passing – where light-skinned Black folk attempt to remake themselves as white. Stella upends her life for the second time, after leaving Mallard, by continuing the theme of abandonment and commiting to whiteness. “She hadn’t adopted a disguise or even a new name. She’d walked in a colored girl and left a white one,” Bennett writes.

When Stella marries a white man and has a child with him, she is afraid that the child will become darker and its hair kinkier, exposing her secret. Her inchoate existence as “white” is shrouded with loneliness and grief, having had to split from her twin and now living with a man whose whiteness reminds her of the men who lynched her father.

Related article:

However, in the act of refusing to live in the racial in-between, she does not quite master her performance. Living in California at a time when the civil rights movement is approaching its peak, Stella depends on performing cruelty to remove herself from being discovered. Living as a white woman, she falls into a life of leisure, crudely acting in ways she would imagine a white woman to conduct herself. Her attempts to free herself from the limitations brought to the fore by blackness only seems to spin herself into a cocoon, the silk threatening to bind her to a life of lies and perpetual fear.

The reader watches as Stella makes villains of the Black family that moves into the neighbourhood, under the racist veil of “keeping the community white”. In doing so, however, Stella is pulled taut by the tension of keeping up her performance of whiteness while seriously considering the possibility of unburdening herself to her Black neighbour. Cognitive dissonance is a major theme in Stella’s life: as a child, alongside her sister, she witnessed the lynching of her father. However, emboldened by her performed whiteness, she uses the same tropes to frame Black people as corrosive to the neighbourhood.

Displacement

Her sister Desiree had her own idyllic plans when she left Mallard, but it is marred by physical, rather than psychological, violence. Abandoned by Stella, Desiree lives like one constantly contending with a phantom limb, navigating the world as a half of a whole. She marries a man who uses his fists as a means to subdue her.

With skin that can easily tell the story of violence, she carries the bruises and blemishes that are meant to shame her for her lightness. In many ways, Desiree is described as a character that regards Mallard’s preoccupation with lightness as silly and superficial. She is often accused of making a child so dark that the only explanation for this “abomination” would be that the child was created out of spite.

Desiree is intentional about throwing away the ideals of her upbringing. Her awareness of the fabric of her own community calls her to confront and subvert the unwritten rules that require her to marry a man just as light or lighter than her. Auxiliary characters throughout the book either comfort Desiree for having a child who is accused of being “obscenely dark” or they attempt to blame her for falling in love with men who so seriously breach their ideas around “acceptable blackness”.

Related article:

The idea of currency being placed on complexion is not a concept unique to the United States, as the residue of colonialism is a global terror. The South African context has a lingering culture of beauty, desirability and value placed on bodies that are visibly lighter and thus closer to whiteness in appearance and treatment – as colonial and apartheid categories and experiences endure. This legacy pervades many aspects of life and culture.

Bennett presents a narrative that illustrates the violence meted out by colourism. We meet Jude, a child who could not be further in complexion from her mother, Desiree. Her journey is one of constant displacement, her life riddled with insults from her own community that are so destructive that they mirror the language of racists.

In Mallard, Bennett creates a town that in its nucleus disparages blackness. She does this in an incredible way that has resonances with Morrison. The writing of Jude as a character is reminiscent of Pecola in Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Like Pecola’s desire for blue eyes, Jude considers how much softer and more pleasant her life would be if she had white features. Pecola’s exchanges and Soaphead Church in Morrison’s novel are astoundingly similar in desperation and desire to Jude watching her grandmother’s alchemic attempts to lighten her.

Identity and self-determination

In the web of intersecting characters, self-determination is a common theme. In some instances, we witness how the decisions made by the twins result in their respective successes and train wrecks, for them and their families.

In 1978, while studying at the University of California, Los Angeles, Jude meets Reese, a transgender man who refuses to acknowledge the problematic idea of a “before”, which eroded Reese’s right to self-identify. The relationship between Reese and Jude is tender and generous, the one loving the traits of the other that society makes a site of their oppression. There is an incredible story of blooming together that exists between the two characters, who come to one another as lovers while acknowledging the parts of themselves that push them to the margins.

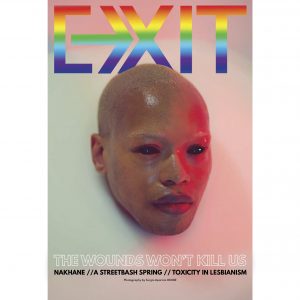

Related article:

In conversation with Jazmine Hughes, a story editor of The New York Times Magazine, for Politics and Prose Bookstore, Bennett confirmed the intentional creation of a world that allows for self-expression and duality. The story goes beyond race and the complications that arise as a result of it. We confront characters who are drag queens, Reese’s desire to be a photographer and the wishes of Kennedy, Stella’s daughter, to become an actress.

Kennedy’s desperate need to be and become something is a tale catapulted by the dishonesty on which her life has been built. Melodrama, irresponsibility and living inauthentically are devices she uses in attempts to find something inside herself worth identifying as authentic. Lies and the act of lying have been an integral part of her childhood as Stella encouraged her to lie in order to hide their association with the Black neighbours. Bennett describes passing as “faking a death”. The implications of Stella’s passing do not only affect her but also facilitate the feelings of loss that Kennedy has. Effectively, by passing, Stella has murdered generations and cleaved all her memories in half. “She hadn’t realized how long it takes to become somebody else, or how lonely it can be living in a world not meant for you,” Bennett writes.

Spanning 40 years, The Vanishing Half is an incredible tale about the consequences of freedom and attempting to free oneself, and the way in which the past constantly laps at the ankles of those running from it.