Can Beitar Jerusalem overcome its bigotry?

Known as the most racist football club, the Israeli side has never signed an Arab player and Muslims who joined the team faced chilling prejudice. But an Arab billionaire says he can change all tha…

Author:

8 April 2021

At first, Maya Zinshtein did not take the threats to her life seriously. They began as a trickle, sporadic emails and text messages that were easily ignored. But it quickly became a deluge of hate as her phone rang non-stop throughout the day.

Her mother was subjected to the same explicit promises of violence. One menacing email simply read, “Your next film will be about your funeral.”

“It was one of the hardest times of my life,” said Zinshtein, an award-winning Israeli documentary filmmaker. “I was totally shocked. But then again, it was not completely unexpected.”

This was in November 2015. The culprits were members of La Familia, a hardcore group of supporters loyal to Beitar Jerusalem, a football club widely described as the most racist in the world. The source of their ire was a 10-minute video on The Guardian newspaper’s website promoting Zinshtein’s Emmy Award-winning documentary Forever Pure.

The film chronicles the tumultuous 2012-2013 season in which two Russian Chechens – 19-year-old Dzhabrail Kadiyev and 23-year-old Zaur Sadayev – signed for the club, making them the first Muslims to wear Beitar’s black-and-yellow strip. It also shines a damning light on Israel’s right wing and exposes the ugly side of unchecked nationalism.

“I wanted to hold a mirror to them, my goal was to bring this from the fringes to the centre of the Israeli discourse,” Zinshtein explained. “It started a conversation. Today, ‘forever pure’ is used as an expression for hostility, not just about Beitar. It’s a film about a club’s season but it tells a wider story.

“Hundreds of moderate fans have told me that they’re heartbroken by what they saw. I say, ‘Good, that’s what you should feel.’ But then members of La Familia did not like how they were presented, even though it was a fair and accurate reflection. That is why they got angry.”

Adding to the febrile atmosphere, the abridged clip was released amid a wave of unrest in Israel and Palestine. It was dubbed the Knife Intifada by international sources, because of the large number of stabbings, and would culminate in the deaths of 266 people in 10 months.

Zinshtein’s phone is once again ringing non-stop. She released her second feature-length film ’Til Kingdom Come: Trump, Faith and Money in February, revealing the bond between Christian evangelicals in the United States and Israeli Jews. But that is not the only reason she is in such demand. The tale of Beitar Jerusalem has taken an unexpected turn.

‘Jews and Muslims can partner together’

La Familia, who have filled the Teddy Stadium with chants of “Death to Arabs” and who take pride that theirs is the only club in Israel never to have signed an Arab player, now face a reckoning. As first reported in December, a member of Abu Dhabi’s ruling family, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, is close to owning 50% of Beitar Jerusalem.

“Honestly, nothing surprises me any more with this club,” Zinshtein said. “I’d heard that something like this could happen. I thought it was an interesting twist. There’ll probably be many before this is over.”

Predictably, there was a backlash as La Familia members were accused of spray painting anti-Arab slogans on walls near the club’s training facilities and chanting “Fuck bin Khalifa”. Undercover police officers subsequently arrested four people as the wheels of change were set in motion.

Related article:

“It is a great opportunity to show the world that Jews and Muslims can partner together and do beautiful things,” said Moshe Hogeg, the Israeli tech billionaire who bought the club in 2018, on the BBC World Football podcast. “It’s a shame to hear people think Beitar is a racist club. It’s not. 99.5% are accepting of everyone. But when a tree grows it grows silently. When it falls it makes a lot of noise.”

The sale has frozen momentarily because of questions about the sheikh’s true wealth. Further documents are required and an audit commissioned by Israel’s football federation has revealed several inactive companies and financial discrepancies. With air travel currently restricted, the deal is on ice. That it has come this far at all already makes this one of the most remarkable narrative arcs in club football.

It was Zinshtein who catapulted Beitar’s story to a wider audience, though that was not her initial intention. She was at Ben Gurion Airport when Sadayev and Kadiyev arrived in the country. Working as a journalist, she was one of the first Israelis to speak to the two young players as part of her assignment to cover their first four days at the club. It soon became apparent that something much larger was bubbling beneath the surface.

“I don’t think they could point to Israel on a map before they arrived,” Zinshtein said. “They knew that the club was unique and had some strong views, but they couldn’t have said what they were. They had no idea what they were about to experience or even why they were there beyond playing football.”

Related article:

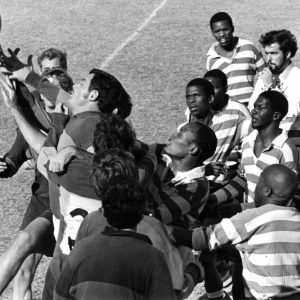

What they experienced was undiluted bigotry. A Beitar supporter attacked Kadiyev during a match while his mother watched in horror from the stands. And even after scoring a goal for Beitar, fans booed Sadayev and left the stadium in protest.

Their arrival precipitated an avalanche of toxicity as former club chairperson Yitzhak Kornfein was subjected to abuse outside his home, with one protester threatening to rape his daughter. The club’s captain and goalkeeper was turned into a pariah after his public endorsement of the transfers. Arsonists torched the club’s office, destroying irreplaceable memorabilia. Fans held aloft a banner stating “Beitar forever pure”, providing a chilling parallel to the concept of a master race purported in Nazi ideology.

The team struggled on the pitch. The six-time champions avoided relegation on the final day of the season. The two young Chechens returned home as soon as they could.

That is what happened. The why is more complex and connects a thread to an Arab royal, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the future of the Middle East.

Beitar’s place in Israeli politics

At the time the club was owned by Arcadi Gaydamak, a Soviet Union-born businessman whose fortune was built partly by trafficking arms to Angola during that country’s civil war. He began his quest to buy influence in Israel in July 2005, by investing large sums of money in various basketball and football teams. Within a few days, he had acquired full ownership of Beitar Jerusalem.

But his mission failed. He won just 3.6% of the vote in Jerusalem’s mayoral election in 2008. This setback meant he turned elsewhere to slake his thirst for influence. He brought his team to Chechnya, Russia’s majority Muslim republic, in January 2013. The friendly match with Terek Grozny ended in a 0-0 draw, but the scoreline was irrelevant. Gaydamak’s plan had worked. Soon after, Kadiyev and Sadayev arrived in Israel to represent the most openly Islamophobic club in the world.

“I assumed there would be a big reaction,” Gaydamak admits on Forever Pure. “That was the purpose. [They were signed] not because they are good footballers [but] to show society as it really is. To expose its real face.

Related article:

“I was never a football fan, I always said that. But Beitar has more fans than all the other clubs in Israel combined. And this is why it’s a very interesting propaganda tool.”

Gaydamak is not alone in viewing the club as a platform for power. It was founded in 1936 by David Horn, a local leader of the Betar Movement, the Revisionist Zionist youth movement contributing to the broader fight for a Jewish ethnostate. Players and administrators at the club had close ties with paramilitary groups. One former striker, Haim Corfu, used his expertise in explosives to assassinate two British police officers in 1939 and served as Israel’s minister of transportation in the 1980s.

Beitar’s popularity grew in the 1990s as they won three league championships during the decade. This period coincided with a rise in hooliganism in European football as well as Benjamin Netanyahu’s inaugural election as prime minister in 1996.

How the club reflects Israel

Netanyahu was Israel’s first political leader to be born in the country after its declaration of independence in 1948 and he has led the right-leaning Likud party with a jingoistic slant. In his 1993 book A Place Among the Nations: Israel and the World, Netanyahu writes that nationalism is “a central driving force in global affairs” and emphasised that the survival of his Jewish state depended on a strong military. Netanyahu, along with many senior Likud politicians, is an ardent fan of Beitar and his name regularly reverberates around Teddy Stadium.

“The racism in the stands has not only been tolerated by government ministers, but encouraged,” said Adie Mormech, a Britain-based activist who works with pro-Palestine pressure groups. “There is complete and utter hate directed towards Arabs.”

Mormech said the part takeover of the club by an Arab sheikh will not change much. “I believe it will result in a backlash,” he said. “Beitar fans are so far gone. What it will do, and this may be a positive, is expose in greater detail the racism and xenophobia that exists. I do not agree with [Hogeg]. It is not a small minority of fans who hold these views. How can it be when these views are woven into the fabric of the country? Palestinians in particular, and Arabs in general, are seen as lesser humans. These fans are just at the sharp end of this racism.”

For what it’s worth, Hogeg has promised to meet this challenge. “We have to eliminate them the same way England dealt with hooligans,” he said of Beitar’s racist fans. “We will personally sue the leaders of La Familia for damaging the reputation of the club. I know and believe that in a year or so we will change this. La Familia won’t be a part of us.”

Related article:

Hogeg’s proposed partnership with Sheikh Hamad comes at an interesting time in the broader geopolitical relationship between Israel and the Arab world. Former US president Donald Trump helped broker the Abraham Accords, a union between Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in September. Marketed as “peace deals” although the countries have never been at war, these agreements have been widely interpreted as a unified stand against Iran.

“Clearly a coalition with the enemy of one’s enemy is palatable, even if there is open racism towards Arabs,” mused Mormech. “The politicians in Bahrain and the UAE obviously don’t care that Palestine is an outdoor prison.”

Zinshtein, too, is sceptical, but hopes that Beitar can indeed move towards a more inclusive identity. She points out that Ali Mohamed, a midfielder from Niger, is currently on the roster. Though he is a Christian, it is still noteworthy that he has been accepted by some at the club.

“It’s a slow process,” Zinshtein said of change. “The season after the film was released, there was a new fan group that tried to go against La Familia. A year later, when La Familia began racist chants, it was other fans who stopped them or drowned them out. Hogeg has been the first owner to openly confront the hate. Then Ali Mohamed signed. Now this deal is close. Change is coming. It has to come.”