Centre of world boxing lies in the east of London

Boxing has been relentlessly Americanised inside and outside the ring. But its heart – and its past, present and future – beats with Britishness from deep in London’s East End.

Author:

8 April 2020

Paradise, they called it. What the hell were they thinking? Paradise Row is a short, narrow cobbled lane fronting a parade of unusually grand old houses in too damn real Bethnal Green in the depths of London’s East End. It is bordered by Paradise Gardens, a small, treed, flowery green patch that has been a public space since 1678.

Bethnal Green Road runs along one side, Cambridge Heath Road along the other. Before the coronavirus lockdown, thousands would bustle through and past there every day, many to or from the adjacent underground station.

Commuters stream into and out of the station’s multiple maws, ignoring the homeless and the hopeless strewn among them as they stride on layers of filth on the pavements, streets and steps. This is not a happy place, particularly when winter bites through every layer of protection you put in its way.

Welcome, pilgrim, to paradise. If you’re a boxing person, that is: you are bang in the middle of a district that has a greater claim to the title of the historical epicentre of the global fight game than Madison Square Garden, the MGM Grand, the Orient Theatre or anywhere else.

The real home of boxing

That remains true even though boxing has been Americanised to within an inch of its proper place in the public consciousness. Blame, among others, Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano, Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, Floyd Mayweather Jr, “Rocky”, Bert Sugar, Michael Buffer and the cruel plastic trench of pay-per-view television.

But before all that came the bare-knuckle era, in which the first English champion, James Figg, died 76 years before the first American king of the ring, Tom Molineaux, was crowned. By then the English title had changed hands 23 times. Molineaux was born into slavery in Virginia in 1784 and, having won his freedom, moved to New York and then to England, where in September 1811 his challenge for Tom Cribb’s England heavyweight championship played out on a raised platform in front of a crowd of 20 000. Cribb prevailed, but it took him 35 rounds.

Related article:

That’s not the only American nod to the grandaddy hood of British boxing. For instance, in 1813 Pierce Egan, born in England of Irish parents, published the first of the five volumes of Boxiana; or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism. He called boxing “the sweet science of bruising”. If that sounds familiar it’s because unarguably the finest book on any sport yet written is titled The Sweet Science.

It was published in 1956 by AJ Liebling, who wrote magnificently on war, the press, food and boxing for the most highbrow of all magazines, the New Yorker. Liebling had the good manners to pay tribute to Egan, whom he idolised as “the greatest writer about the ring who ever lived”.

Among those Egan chronicled was a man who lived at No 3 Paradise Row, and who perhaps thought his address would bring him contentment. In his day he was the best fighter in the business. He burned with such anger even after he retired that he would get into fights on his way to watch other people fight. A circular blue plaque now hangs above what was, for more than 30 years, his front door. The inscription: “Daniel Mendoza. Pugilist. 1764-1836. English Champion who proudly billed himself as ‘Mendoza the Jew’, lived here when writing The Art of Boxing.”

Related article:

He invented the jab and was the first boxer to move sideways in the ring and to duck and block punches. Until then it was considered cowardly not to stand still and let fly until one fighter went down. And stayed down. These innovations helped Mendoza win the heavyweight title despite standing only 1.7m and weighing just 73kg. He became a sensation, a subject for poets, portrait painters and songwriters.

His celebrity grew to the point where he was heralded as “the first Jew to talk to King George III”. He originally met his majesty when he was merely his highness, the prince of Wales – a firm fan who arranged at least one of Mendoza’s fights, bet vast sums on him, paid him bonuses after lucrative winnings and shook his hand in public; unheard of for so prominent a personage in those archly antisemitic times. You could call him the royal promoter.

If you stand on Mendoza’s doorstep and look left you might, skyline permitting in a city where buildings go up almost as fast as they come down, catch a glimpse of York Hall just more than 250 metres away down Old Ford Road. Opened in 1929, it offered impoverished East Enders unimagined amenities: two public swimming pools, Russian and Turkish baths, and a laundry for all. But it has long been better known as the home of British boxing, which was first staged there in the 1950s.

British world champions

It was at York Hall in January 1990 that Lennox Lewis earned a second-round technical knockout over Noel Quarless in the seventh fight of a professional career then barely seven months old. Joe Calzaghe needed only 85 seconds to dispense with Frank Minton there on Valentine’s Day 1995. David Haye made his debut at York Hall in December 2002 and fought there four more times. Carl Froch reeled off consecutive victories in his first four pro bouts there, all in 2002, and returned three times after that. All are British and all became world champions.

Related article:

Rightward from Mendoza’s doorstep not 200 metres down Bethnal Green Road is W English and Son Funeral Directors, known locally as “the undertakers of the underworld”. The firm presided over the internments of Charles, Reggie and Ronnie Kray between 1995 and 2000. The Kray brothers, in particular twins Reggie and Ronnie, were vicious 1960s gangsters who have been undeservedly mythologised as local heroes far beyond the streets of the neighbourhood that spawned them. In March 1969 they were jailed for at least 30 years for the murder of two other gangsters. That was a far cry from 11 December 1951, less than two months after their eighteenth birthdays, when the twins appeared on the same bill in lightweight six-rounders at no less a venue than the Royal Albert Hall.

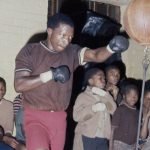

The Krays learnt part of their rough trade a kilometre away from Mendoza’s place at Repton Boys Club on Cheshire Street, which has been around since 1884 and is still considered the best producer of amateur champions in Europe. One of the Repton’s more recent graduates, 2000 Olympic gold medallist Audley Harrison, lost a heavyweight world title bid against Haye in November 2010.

The gritty red-brick, white tiled clubhouse – which was a bathhouse in the Victorian era – featured in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. In The Repton, a 2013 short film by Alasdair McLellan, former member and hardman actor Ray Winstone tears up when he says: “You got to meet people that you wouldn’t necessarily meet in the street, because everyone kept their self to their self. So you learnt something about morality, about respect and about discipline. And that will stand you in good stead for the rest of your life. I learnt my basics and my thoughts on life in this gym; in this gaff here. And that’s why I can never forget about this club. It’s in me.”

You can’t fail to notice British boxers currently, what with Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury holding all five versions of the heavyweight title between them. The most keenly anticipated confirmed bouts in that division in the world so far this year were Daniel Dubois’ showdown with Joe Joyce, Dillian Whyte taking on Alexander Povetkin, Oleksandr Usyk versus Dereck Chisora and Joshua’s fight against Kubrat Pulev. Dubois, Whyte, Chisora and Joshua are all British, and all of those clashes are scheduled for London or Manchester. That’s if the coronavirus doesn’t knock them out, as has happened with the postponement of Dubois-Joyce from 11 April to 11 July.

Related article:

The third act of the gripping Fury-Deontay Wilder drama was tentatively scheduled for Las Vegas on 18 July before it too was moved by the virus, possibly to October, and the one, the only, the super fight – Fury versus Joshua – is quietly on the cards for December. Not so fast. Fury is in the ESPN camp and Joshua is with DAZN, a subscription sports streaming service. Another obstacle is that Fury is promoted by American Bob Arum, who has formed a firm partnership with British veteran Frank Warren. Joshua’s promoter is Barry Hearn, a brash young Brit whose stable features 14 other world champions – among them Cecilia Braekhus and Katie Taylor, the undisputed welterweight and lightweight queens.

But the unprecedented riches offered by the prospect of the two most marketable boxers in the world – both of them British – touching gloves in the centre of the ring, in front of 90 000 at Wembley Stadium, say, will force compromise. You could call that paradise.