Chidinma Nnoli imagines being and what might be

The Nigerian artist’s debut solo exhibition, To Wander Untamed, posits a space for women in which freedom from oppressive patriarchy and prescriptive religion is a possible dream.

Author:

19 March 2021

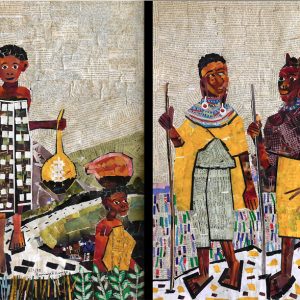

There is a profound poetry in the lush pastels of Chidinma Nnoli’s paintings. Densely holding multiple meanings, her weighted coats of paint present a world of layered interpretations, plural and expansive. With her first solo exhibition, Nnoli’s distinctive artistic language delicately and determinedly expresses intentions that so intimately concern themselves with freedom – at once personal, communal and deeply political – in a way that registers with and gestures towards us all. We are invited into a conversation about liberty: hers, ours, each other’s.

Nnoli draws out a literary sensibility. In paint-prose, the storyboarded works are meant to be read in order. To Wander Untamed unfolds in a journey of becoming that invites and invokes the duality of “perspective” as a way of looking and reading. In doing so, she astutely implicates the viewer in the frames of the works and the framing of their narrative. In our ways of seeing, we are seen too; the double meaning of “reflections” is brought to the surface.

This is an architecture of experience. In the radical space and place making of To Wander Untamed, there is a constant and insistent dialogue between the frames she constructs and the viewer, as she reckons with the structures of this world and still imagines life and self, anew, with a feminist hope.

We begin with a window at a curved arch, the calling card of cathedrals. This entry point appears first as if no entry at all. Opaque, it’s a sign that we are about to see what we are not meant to, beyond appearances and “through the looking glass”.

The work grounds itself in these frames by means of repetition. They guide and simultaneously question our eyes, a gaze that gazes back. As a narrative device, these windows are a site that asks much of sight. What it is to look, see, regard and reflect is always in question here.

Nnoli operates first by allusion, allowing the story to develop and deepen over the course of the works. She sets the scene through markers of experience: crosses, prayer beads, titles like Did You Sin Today?, a haloed protagonist. And as the story opens up, the world of her women does too.

Religion and patriarchy

This is a space that centres their story against the imposing grand narratives of religion and patriarchy. “Most of my subjects are myself, my sisters, my friends,” Nnoli says. And in art’s forever awe-inspiring alchemy, her windows become a mirror to our own experience.

With each repetition of the frame, her artistic device, Nnoli insists on our engaged attentiveness. She asks that we pay incisive attention to subtle shifts as she constantly offers more information, adding subtext and texture to the narrative. It becomes meaningful, then, when an arm extends outside a window, when figures appear on the balcony in a space outside the walls that structure their lives: as a breath and a dream.

These works rustle with reckoning, as Nnoli explores how the built environment of patriarchy inscribes our selves and prescribes our ways of being. While we live within these structures, they live in us too. And as the artist reflects, it’s “a lot to rid yourself of”.

Related article:

Still, Nnoli does not resign herself or her figures to a confined existence. In the poetics of the personal, she locates not only its pervasive and invasive politics but also its possibilities. With tenderness and certitude, her work invites us to think beyond the binaries of inside versus outside, individual versus communal, self versus other, family versus stranger, freedom versus oppression, structure versus agency, and still more. She does this through expansively imaginative work.

“I take them out of this environment that they exist in here and put them in this perfect environment, this reimagined environment where you have florals,” Nnoli says of the women in her work. This relocation is rooted in her concern with creating spaces of safety within which their power “to dream…[is] limitless”. While these women are framed by the oppressive structures of their daily lives, in all the works they are also enveloped by florals – cradled even as they are contained.

In creating a world beyond those oppressive windows and walls, she reframes their lives as ones not solely defined and delimited by religious patriarchy. As her female figures imagine and build a life beyond the walls that contain and constrain their bodies, Nnoli’s impressionist flowers become tactile and living representations of their imagination and consciousness in bloom. This lush universe is present from the very first frame, telling us that there is beauty, joy and pleasure here too. It is a reminder of what can be fashioned by our hands. There are alternate worlds to be built.

Communal care

And this possibility of freedom rests on the communal. Solace resides in shared experience and resistance. It finds expression through heads resting each other’s shoulders, bodies turned towards each other. These women find in each other a source of comfort and strength in the cold, Catholic conditions of their existence. Nnoli’s Dreamscape and Escape presents a different kind of fellowship.

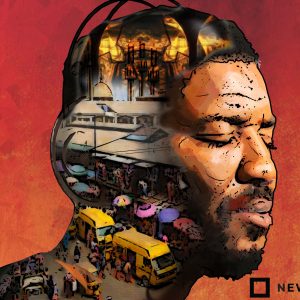

To wander, here, is also to wonder, to think of the present not only as constraint but to keep the possibility of the future alive. To mindfully borrow and gently remake a phrase from Ghanaian intellectual Ato Sekyi-Otu, Nnoli’s works do not present an oppressive reality as “all there is to be” and “all there is to be known”. Rather, to reorient Sekyi-Otu’s meditation on African philosophy, “they wonder aloud what the world and the drama of human life would look like, what promises and predicaments they might proffer, were they ever unshackled from the constraints of a particular time and place, a particular historical circumstance”. And a particular experience.

Related article:

With this work, Nnoli wanders and wonders what a liberated future might look like and require from us. Her “conscious present” is constructed out of “a consciousness of the possibility of freedom, intimations of what the nature of things might” be and become. “There is a freedom that I am looking for,” Nnoli says, “and I’m looking to see how much I can push the freedom within my work.”

In conversation, Nnoli names this debut a “coming-of-age story”. And she dismisses any idea of finality, saying, “I don’t think the journey towards finding yourself ends.” There is no neat end with the final frames: the return of the window, adored anew in petals. She asks whether we aren’t always coming of age, becoming, in process? As Angela Davis reminds us, “freedom is a constant struggle”.

These works began as poetry shared online. Their imagery is recreated from this inspiration. In returning to these words, Nnoli is always thinking beyond the frame:

In a shape is where I stay

I use the word stay

Because I don’t live there

I want to live somewhere else

Maybe sky rocket to the sun

What an image to invoke – to make a place elsewhere, to build a new architecture in which to reside. It is a place where she writes that “nothing hurts anymore”. What a future to imagine.

In the final figurative image of the exhibition, The sacred heart of Mary, Nnoli returns to the solo protagonist. The halo now is perhaps a divine indicator that we can all be a sun to ourselves and to each other.

To operate by intimation is to move by what one considers in one’s gut to be true, trusting what is intuited as a steady assurance on a journey as difficult as liberation. And with the narrative closing of her window, Nnoli leaves an openness still – to the future, for us all.

This is a lightly edited version of an essay that appears in the catalogue for To Wander Untamed, which is on at the Rele Gallery in Lagos.