Durban’s street traders hobbled by punitive permits

In an economy devastated by Covid-19 and the riots, eThekwini’s street sellers want the municipality to abolish the system that keeps them waiting in queues and running from cops.

Author:

11 August 2021

The City of Durban has 45 700 street traders who collectively pay millions of rands to the eThekwini municipality to sell goods on the pavement. Many of these people live perilously close to the breadline. After the looting in July, it will take months for shops to reopen in Durban’s central business district, making their tenuous existence even more precarious.

Asiye eTafuleni (AeT), a non-profit organisation that advocates for street traders, says about 460 000 people traverse Warwick Junction, the city’s busiest intermodal transport intersection, every day. But about 30% of the people who would ordinarily go into the business district will not be doing so anytime soon because many shops have been destroyed.

AeT co-founder Richard Dobson says that if ever there was a time for Durban to live up to its slogan of being a “caring city”, it would be now.

During the riots, grocery stores were either looted, destroyed or closed their doors, and food queues formed in KwaZulu-Natal. AeT called on the municipality to quickly re-establish street trading in Warwick Junction because these sellers are more nimble than supermarket behemoths.

Related article:

“Traders are fleet-footed,” Dobson says. “They can knock up a table and sell spinach that can feed people quickly. This doesn’t rely on big organisations. We obviously need huge supply chains at scale. But where convoys of big trucks are vulnerable, bakkies ferrying fruit and vegetables are less so.”

The City should help kickstart the informal economy, Dobson adds. “People are desperate. The people we are speaking to are in tears. In an economy wracked by Covid and unrest, people have turned to the streets to survive. We should relieve the pressure.”

The looting has similarly affected Durban’s waste pickers. An AeT study in 2012 showed that these people collected 150 tonnes of cardboard and paper around eThekwini every day. But with many retailers closed, much of this is not available.

Arbitrarily policing permits

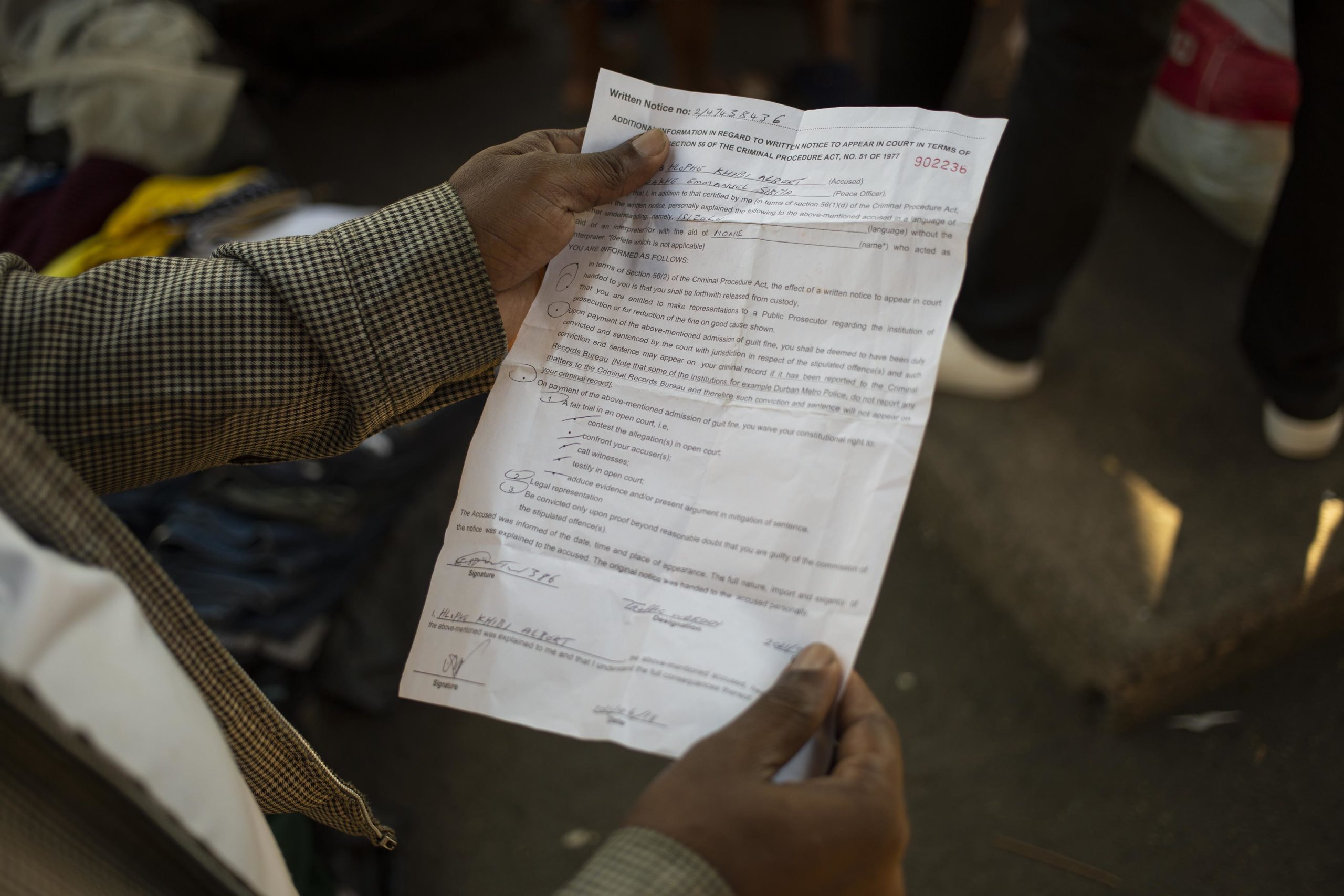

Workers in South Africa’s informal economy account for 5% of the country’s gross domestic product, but government policies are largely hostile to this sector. Dobson’s colleague and AeT co-founder Patrick Ndlovu is at the forefront of monitoring the harassment of street traders, most of whom require a permit to operate.

A permit costs at least about R560 a year and traders without one are fined and have their goods confiscated. But the permit is almost impossible to renew, because the municipality’s business support unit is understaffed and its processes cumbersome, the traders say.

Smangele Ngcobo, 29, is too scared to leave her goods on the pavement in the care of her peers to go to the toilet. She is worried she will be fined. Ngcobo says she was fined R600 on two consecutive days and her goods were seized.

Albert Sihlope, 50, sells vegetables in the same spot on which his family has traded for decades. Though his family has a permit, it is not in Sihlope’s name. A relative’s name appears on the document. “I have been to [the business support unit] so many times. I waited for a long time and they said I am not on the system, but my family was allocated a site.”

“We plead with the police not to confiscate our goods because it is our livelihood, but they do,” says Thandeka Zungu, 42. “We have applied for sites from before the lockdown but you just wait in the queue at [the business support unit]. You don’t get a receipt or a reference.”

Street sellers say there is no order or consistency in the management of traders. Officials and the police behave arbitrarily. “The police here are God. Sometimes they give you a chance, sometimes not. It is a money-making scheme,” says Thoko Mabaso, 66. “The police come in a convoy and they just jump on us like we are hardened criminals. The best thing to do is pack your goods quickly and run.”

“I look after four grandchildren,” says Thembisile Ndlovu, 70. “I have been trading since 1986. When the police come, they are harsh. We try to take pictures of them on the cellphone and they shout at us to put the camera away.”

Ngcobo says most traders have no option but to turn to loan sharks to replace seized stock or pay fines. “It took me three months to save R3 500 for stock. Profits don’t come easy. You get a little bit every day. I am a single parent, and I work here seven days a week.”

‘They treat us like dirt’

AeT’s Ndlovu says the permit system is so dysfunctional it is almost worthless, and traders receive very little support in return from the City. Cleaners are scarce and overburdened, the toilets are filthy and traders often bring their own water to clean fresh produce. They say the system “criminalises” them.

Ndlovu says that when they challenge fines they have to wait months before they can plead their case in the municipal court. When traders’ goods are confiscated, these are often not itemised or registered. Ndlovu questions how the business support unit allocates trading, echoing the street sellers’ claims that it is haphazard.

Scelo Mabaso, 45, says: “They [officials and police] don’t care. This is harassment. Why do they want to instil fear and make money from us? They are arrogant. They treat us like dirt.”

eThekwini spokesperson Msawakhe Mayisela says the City advertises vacant or newly developed trading sites quarterly in its newspaper. The allocation is done to support, grow and provide opportunities for new entrants. “It is a useful tool for job creation and for the inclusion of the people who were excluded from economic activity in the past.”

Mayisela says it takes six weeks to process a permit and this is communicated in writing or via text message. The metro police, he adds, confiscate goods and conduct daily operations to ensure traders comply with by-laws and have valid permits. Receipts are issued for goods seized.

Traders pay R47 a month for a site without shelter, R79 for a site with a shelter and R379 a month for a bigger “business hive” site. Mayisela says the City uses the money from permits to develop trading facilities, remove garbage, provide security, water, electricity and storage facilities, and to do maintenance. He says the City’s approach to the sector is “developmental”. Its economic recovery plan allows a six-month rental holiday for traders with valid permits.

A new paradigm

Verushka Memdutt, general secretary of the Market Users Committee in Durban, disputes the City’s claims that its permit system is managed well. “It is not. We have traders who have been seeking permits for over five years. The permit system is nonsense. It is used by City managers to lord over people. No government should be charging informal traders who are trying to survive.”

Dobson asks how the City determines which sellers can ply their trade. “The permit system is ostensibly to stop overtrading, but who are we to say R20 in earnings for someone doesn’t count? Nobody is going to sit on the street and make no money.”

He says guidelines released by the South African Local Government Association on public space and trading were aimed at the functionality of public spaces and should be used as a “route out of the regulatory and enforcement cul-de-sac that local government has been caught in over the last 20 years, to the detriment of the informal sector”.

“Really, what we need now is an urgent moratorium on permits. We are not being creative and constructive. We need a planning scheme that looks at trading thresholds and spatial and management dictates that can be jointly negotiated. We need a new paradigm.

“Politicians and officials talk about the City being ‘caring’ and the phrase flips off their tongues. What does it mean if you punish people for trying to feed their families every day?”